Who Owns the Future? (50 page)

Read Who Owns the Future? Online

Authors: Jaron Lanier

Tags: #Future Studies, #Social Science, #Computers, #General, #E-Commerce, #Internet, #Business & Economics

Computation can offer precisely this kind of feedback all too easily. Watch a child playing games on a tablet and then watch someone keeping up with social media, or trading stocks online. We become obsessively engaged in interactions with approximately, but not fully predictable, results.

The intrinsic challenge of computation—and of economics in the information age—is finding a way to not be overly drawn into dazzlingly designed forms of cognitive waste. The naïve experience of simulation is the opposite of delayed gratification. Competence depends on delayed gratification.

This book has proposed an approach to an information economy

based more on the craft of usability than on the thrill of gaming, though it doesn’t reject that thrill.

Know Your Poison

To paraphrase what Einstein might or might not have said, user interface should be made as easy as possible, but not easier. Dealing with our personal contribution of data to the cloud will sometimes be difficult or annoying in any advanced information economy, but it is the price we will have to pay. We will have to agree to endure challenges if we are to take enough responsibility for ourselves to be free when technology gets really good. There is always a price for every benefit.

When I try to imagine the experience of living in a future humanistic network economy, I imagine frustrations. There will constantly be a little ticker running, and you’ll be tempted to maximize the value recorded. For many people, that might become an obsessive game that gets in the way of a more authentic, less prescribed experience of life. It will narrow perspectives and undervalue wisdom. There will be nothing fundamentally new, in that money has always presented exactly that distraction, and yet the temptation could become more comprehensive, thicker in the air.

Information always underrepresents reality. Some of the contributions you make will be unrecognized in economic terms, no matter how sophisticated the technology of economics becomes. This will hurt. And yet by making opportunity more incremental, open, and diverse than it was in the Sirenic era, most people ought to find some way to build up material dignity in the course of their lives.

The spiritual challenge will remain of not losing touch with that core of experience, that little something that doesn’t fit into the aspects of reality that can be digitized.

I don’t for a moment claim to have proposed a perfect solution. Someone like me, a humanist softie, will complain about the oppressive feeling of having to feed information systems in order to get by.

The only response, which I hope will be remembered should this

future come about, is that the complaint is legitimate, and yet the alternative was worse. The alternative would have been feeding data into Siren Servers, which lock people in by goading them into free-will-leeching feedback loops so that they become better represented by algorithms.

We are already experiencing designs related to the kind of ticker I dread, except the present versions are much worse. Your Klout

*

score, for instance, is worse than the micropayments you’d accumulate in a humanistic economy because it’s real-time instead of cumulative. You must constantly suck at the teat of social media or your score plummets. Klout dangles a classical seductive feedback loop, almost making sense, but not quite.

*

Klout is a universal, uninvited ranking service that rates how influential people are, mostly by analyzing social media services like Twitter. Amazingly, Klout scores have influenced hiring. Since I don’t use social media, I presumably have a Klout score of zero, which ought to be the superlative status symbol of our times.

In a humanistic information economy, you’d spend your money in ways you choose; under today’s system, you are influenced by phantasms like Klout scores in ways you’ll never know.

1

Perversely, such a sense of mystery can make a bad design more alluring, not less.

Is There a Test for Whether an Information Economy Is Humanistic?

One good test of whether an economy is humanistic or not is the plausibility of earning the ability to drop out of it for a while without incident or insult.

Wealth and dignity are different from a Klout score. They are states of being, not instant signals. It is the latitude granted by the hysteresis—the staying power—of wealth that translates into practical freedom.

One should be able to earn the latitude to test oneself, and try out different life rules, especially in youth. Can you drop out of social media for six months, just to feel the world differently, and

test yourself, in a new way? Can you disengage from a Siren Server for a while and handle the punishing network effects? If you feel you can’t, you haven’t really engaged fully with the possibilities of who you might be, and what you might make of your life in the world.

People still ask me every day if they should quit Facebook. A year ago it was just a personal choice, but now it has become a choice that comes with a price. The option of not using the services of Siren Servers becomes a trial, like living “off the grid.”

It’s crucial to experience resisting social pressure at least once in your life. When everyone around you insists that you’ll be outcast and left behind unless you conform, you have to experience what it’s like to ignore them and chart your own course in order to discover yourself as a person.

It can be doubly tricky because the way people talk about conformity is often as though it were a form of resistance to conformity. It is exactly when others insist that it’s a sign of being free, fresh, and radical to do what everybody’s doing that you might want to take notice and think for yourself. Don’t be surprised if this is really hard to do.

My suggestion is, experiment with yourself. Resign from all the free online services you use for six months to see what happens. You don’t need to renounce them forever, make value judgments, or be dramatic. Just be experimental. You will probably learn more about yourself, your friends, the world, and the Internet than you would have if you never performed the experiment.

There will be costs, since the way we do things today is vaguely punitive, but the benefits will almost certainly be worth it.

Back to the Beach

I miss the future. We have such low expectations of it these days. When I was a kid, my generation reasonably expected moon colonies and flying cars by now. Instead, we have entered the big data era; progress has become complicated and slow. Genomics is amazing, but the benefits to medicine don’t burst forth like a lightning

bolt. Instead they grow like a slow crop. The age of silver bullets seems to have retired around the time networking got good and data became big.

And yet, the future hasn’t vanished completely. My daughter, who turned six as I finished this book, asks me: “Will I learn to drive, or will cars drive themselves?” In ten years, I imagine, self-driving cars will be familiar, but probably not yet ubiquitous. But it’s at least possible that learning to drive will start to feel anachronistic to my daughter and her friends, instead of a beckoning rite of passage. Driving for her might be like writing in longhand.

Will she ever wear the same dress twice as an adult? Will she recycle clothes into new objects, or wash them, as we do today? At some point in her life, I suspect laundry will become obsolete.

These are tame speculations. Will she have to contend with the politics of extreme and selective artificial longevity? Will she have to decide whether to let her children play with brain scanners? Will there be crazed mobs that believe the Singularity has occurred?

Say almost anything bold about the future and you will almost certainly sound ridiculous to someone, probably including most people in the future. That’s fine. The future should be our theater. It should be fun and wild, and force us to see everything in our present world anew.

My hope for the future is that it will be more radically wonderful, and unendingly so, than we can now imagine, but also that it will unfold in a lucid enough way that people can learn lessons and be willful. Our story should unfold unbroken by perceived singularities or other breaches of continuity. Whatever it is people will become as technology gets very good, they will still be people if these simple qualities hold.

APPENDIX

First Appearances of Key Terms

Antenimbosia | |

Big Business Data vs. Big Science Data | |

Economic Avatar | |

Energy Landscape | |

Golden Goblet | |

Humanistic Information Economics | |

Humor | |

Levee | |

Local/Global Flip | |

Nelsonian | |

Punishing Network Effect vs. Rewarding Network Effect | |

Siren Server | |

Software-Mediated | |

Space Elevator Pitch | |

Tree vs. Graph | |

Two-Way Links | |

VitaBop (or Bop, Bopper, etc.) |

Acknowledgments

I gratefully acknowledge

Playboy, The New Statesman, Edge, Communications of the ACM, The New York Times,

and

The Atlantic

for allowing me the space to develop some material that appears in this book, often in significantly different form.

Thanks to Microsoft Research for putting up with a controversial researcher. To say the least, nothing I write was vetted by anyone at Microsoft prior to publication, and this book in no way represents anything related to company thinking or positions. This book is all me, for better or worse.

Thanks to attendees at my talks in 2011 and 2012 for listening to my nascent presentations of these ideas, in which I learned how to express them. Thanks to Lena and Lilibell for putting up with me as I disappear into projects like this book.

Thanks to my early readers: Brian Arthur, Steven Barclay, Roger Brent, John Brockman, Eric Clemons, George Dyson, Doyne Farmer, Gary Flake, Ed Frenkel, Dina Graser, Daniel Kahneman, Lena Lanier, Dennis Overbye, David Rothenberg, Lee Smolin, Jeffrey Soros, Neal Stephenson, Eric Weinstein, and Tim Wu.

Thanks to the musical instrument makers and dealers of Berkeley, Seattle, New York City, and London for providing delightful opportunities for procrastination.

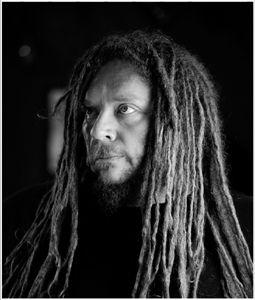

© JONATHAN SPRAGUE

Jaron Lanier

is a computer scientist and musician, best known for his work in virtual reality research. He coined and popularized the term, and he received a Lifetime Career Award from the IEEE in 2009 for his contributions to the field.

Time

named him as one of the “Time 100” in 2010. A profile in

Wired

described him as “the first technology figure to cross over to pop-culture stardom.” Lanier and friends co-created start-ups that are now parts of Oracle, Adobe, and Google. He has received multiple honorary PhDs and other honors. Lanier also writes orchestral music and plays a large variety of rare acoustic musical instruments. He is currently at work with colleagues at Microsoft Research on intriguing unannounced projects.

www.jaronlanier.com

FORE MORE ON THIS AUTHOR:

Authors.SimonandSchuster.com/Jaron-Lanier

MEET THE AUTHORS, WATCH VIDEOS AND MORE AT

SimonandSchuster.com

Also by Jaron Lanier

You Are Not a Gadget: A Manifesto

We hope you enjoyed reading this Simon & Schuster eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Simon & Schuster.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

Notes

First Interlude: Ancient Anticipation of the Singularity