Why the West Rules--For Now (55 page)

Read Why the West Rules--For Now Online

Authors: Ian Morris

Tags: #History, #Modern, #General, #Business & Economics, #International, #Economics

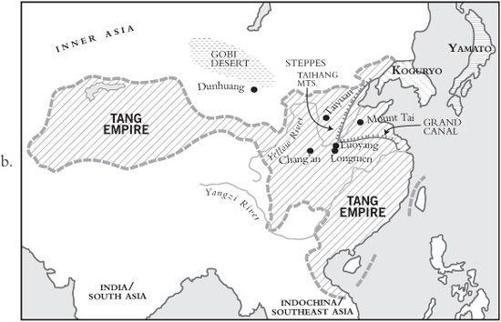

Figure 7.2. The East bounces back, 400–700.

Figure 7.2

a shows the states of Western Wei, Eastern Wei, and southern China’s Liang dynasty in 541. The Sui dynasty united all three in 589.

Figure 7.2

b shows the greatest extent of the Tang Empire, around 700.

We also saw in

Chapter 6

that the Eastern core’s old heartland in the Yellow River valley fragmented into warring states after 300 and millions of northerners fled southward. The exodus converted the lands south of the Yangzi from the underdeveloped periphery they had been in Han times into a new frontier. The refugees entered an alien landscape, humid and hot, where their staples of wheat and millet grew poorly but rice flourished. Much of this land was lightly settled, often by people whose customs and languages were very different from those brought by the north Chinese immigrants. Amid the sort of violence and harsh dealing that characterizes most colonial landgrabs, the immigrants’ weight of numbers and tighter organization steadily pushed the earlier occupants back.

Between 280 and 464 the number of people listed as taxpayers south of the Yangzi quintupled, but the migration did not just bring more people to the south. It also brought new techniques. According to an agricultural handbook called

The Essential Methods of the Common People

, no fewer than thirty-seven varieties of rice were known by the 530s, and transplantation (growing seedlings in special beds for six weeks, then moving them to flooded paddies) had become the norm. This was backbreaking work, but guaranteed high yields.

The Essential Methods

explains how fertilizers let farmers work fields continuously rather than leaving them fallow, and how watermills—particularly at Buddhist monasteries, which were often built by fast-flowing mountain streams and often had the capital for big investments—made it cheaper to grind grains into flour, mill rice, and press oil from seeds. The result was the gradual development of a new frontier of agricultural opportunities, rather like the one the Romans created when they conquered western Europe in the first century

BCE

. Gradually, over the course of centuries, the south’s rural backwardness was turned into an advantage.

Cheap transport began to complement cheap food. China’s rivers were still no substitute for the waterways that the Mediterranean had provided Rome, but little by little human ingenuity made up for this. Underwater archaeologists have not yet provided statistics like those for Roman shipwrecks, but written records suggest that vessels were getting bigger and faster. Paddleboats appeared on the Yangzi in the 490s, and from Chengdu to Jiankang rice fed growing cities, where urban markets encouraged cash crops such as tea (first mentioned in

surviving records around 270 and becoming a widespread luxury by 500). Grandees, merchants, and monasteries all got rich on rents, shipping, and milling in the Yangzi Valley.

The ruling court in Jiankang, however, did not get rich. In this regard its situation was less like the Roman Empire’s than like eighth-century-

BCE

Assyria’s, where governors and landowners, not the state, captured the fruits of growing population and trade—until, of course, Tiglath-Pileser turned things around. Southern China, however, never got a Tiglath-Pileser. Once in a while an emperor managed to rein in the aristocracy and even tried to reconquer the north, but these efforts always collapsed in civil war. Between 317 and 589 five successive dynasties ruled (after a fashion) from Jiankang.

The Essential Methods

suggests that sophisticated agriculture survived in the north into the 530s, but well before then long-distance trade and even coinage had faded away as mounted robbers plundered widely. At first this breakdown produced even more political chaos than in the south, but gradually new rulers began imposing order on the north. Chief among them were the Xianbei, who came from the fringes of the steppes in Manchuria. Like the Parthians who had overrun Iran six centuries earlier, the Xianbei combined nomad and agrarian traditions, and had for generations fought as an equestrian elite while extracting protection money from peasants.

In the ruins of northern China in the 380s the Xianbei set up their own state, called Northern Wei.

*

Instead of just robbing the Chinese gentry, they worked out deals with them, preserving at least some of the salaried bureaucrats and taxes of the old high-end states. This gave Northern Wei an edge over the disorderly, brawling mobs that ran north China’s other states; enough of an edge, in fact, for Northern Wei to unite the whole region in 439.

That said, the deals Northern Wei cut with the surviving remnants of the old Chinese aristocracy remained rather ramshackle. Most Xianbei warriors preferred herding flocks to hobnobbing with literati, and

even when the riders did settle down they generally built their own castles to avoid having to rub shoulders with Chinese farmers. Their state remained determinedly low-end. So long as they were just fighting other northern robber states that was fine, but when Xianbei horsemen approached the suburbs of Jiankang in 450 they discovered that although they could win battles and steal everything not nailed down, they could not threaten real cities. Only a proper high-end state with ships, siege engines, and supply trains could do that.

Unable to plunder southern China because they lacked a high-end army, and running out of opportunities to plunder northern China because they already ruled it, the kings of Northern Wei were getting seriously short of resources to buy their supporters’ loyalty—a potentially fatal weakness in a low-end state. In the 480s Emperor Xiaowen realized that only one solution remained: to move toward the high end. This he did with a vengeance. He nationalized all land, redistributed it to everyone who would register for taxes and state service, and—to make the Xianbei start thinking and acting like subjects of a high-end state—launched a frontal assault on tradition. Xiaowen banned Xianbei costume, replaced Xianbei with Chinese family names, required all courtiers under thirty to speak Chinese, and moved hundreds of thousands of people to a new city at the hallowed site of Luoyang.

Some Xianbei gave up their ancestral ways and settled into ruling like regular Chinese aristocrats, but others refused. Culture wars escalated into civil wars, and in 534 Northern Wei split into Eastern (modernizing) and Western (traditionalist) states. The traditionalists, clinging to nomadic lifestyles, were able to keep attracting horsemen from the steppes, and soon it looked like their military muscle would overwhelm the revolution Xiaowen had begun. Desperation, however, served as the mother of invention. Where Xiaowen had tried to turn Xianbei warriors into Chinese gentlemen, his successors now did the opposite, giving Chinese soldiers tax breaks, appointing Chinese gentry as generals, and allowing Chinese warriors to take Xianbei names. The peasants and literati learned to fight, and in 577 rolled over the opposition. It had been a long, messy process, but a version of Xiaowen’s vision finally triumphed.

The result was a sharply polarized China. In the north a high-end state (renamed the Sui dynasty after a military coup in 581) with a

powerful army sat atop a fragmented, run-down economy; in the south, a fragmented state with weak institutions tried, but largely failed, to tap the wealth of a booming economy.

This sounds utterly dysfunctional, but it was in fact perfect for jump-starting social development. In 589 Wendi, the first Sui emperor, built a fleet, took over the Yangzi Valley, and flung a vast army (perhaps half a million men) at Jiankang. Thanks to the extreme military imbalance between north and south, the city fell within weeks. When they realized that Wendi actually intended to tax them, southern China’s nobles rose up en masse, reportedly disemboweling—even eating—their Sui governors, but they were defeated within the year. Wendi had conquered southern China without grueling wars that devastated its economy, and an eastern revival took off.

WU’S WORLD

By re-creating a single huge empire, the Sui dynasty did two things at once. First, it allowed the strong state based in northern China to tap the south’s new economic frontier; and second, it allowed the south’s economic boom to spread all across China.

This was not always deliberate. When the Sui emperors built the greatest monument of the age, the 1,500-mile-long, 130-foot-wide Grand Canal that linked the Yangzi with northern China, they wanted a superhighway for moving armies around. Within a generation, though, it had become China’s economic artery, carrying rice from the south to feed northern cities. “

By cutting through

the Taihang Mountains,” seventh-century scholars liked to complain, “Sui inflicted intolerable sufferings on the people”; yet, the scholars conceded, the canal “provided endless benefits to the people … The benefits they provide are enormous indeed!”

The Grand Canal functioned like a man-made Mediterranean Sea, changing Eastern geography by finally giving China the kind of waterway ancient Rome had enjoyed. Cheap southern rice fed a northern urban explosion. “

Hundreds of houses

, thousands of houses—like a great chessboard,” the poet Bai Juyi wrote of Chang’an, which once more became China’s capital. It sprawled across thirty square miles, “like a huge field planted with rows of cabbages.” A million residents

thronged tree-lined boulevards up to five times as wide as New York’s Fifth Avenue. Nor was Chang’an unique; Luoyang was probably half its size, and a dozen other cities had populations of a hundred thousand.

China’s recovery was something of a double-edged sword, though, because the fusion of northern state power and the southern rice frontier cut two ways. On the one hand, a burgeoning bureaucracy organized and policed the urban markets that enriched farmers and merchants, pushing social development upward; on the other, excessive administration put a brake on development by shackling farmers and merchants, regulating every detail of commerce. Officials fixed prices, told people when to buy and sell, and even ruled on how merchants could live (they could not, for instance, ride horses; that was too dignified for mere hucksters).

Civil servants regularly put politics ahead of economics. Instead of allowing people to buy and sell real estate, they preserved Xiaowen’s system, claiming all land for the state and merely loaning it to farmers. This forced peasants to register for taxes and kept powerful landlords in check, but tangled everything in red tape. For many years historians suspected that these land laws told us more about ideology than reality; surely, scholars reasoned, no premodern state could handle so much paperwork.

*

Yet documents preserved by arid conditions at Dunhuang on the edge of the Gobi Desert show that eighth-century managers really did follow these rules.

Farmers, landlords, and speculators of course found ways to evade the regulations, but the civil service steadily swelled to fill out mountains of documentation and went through a revolution of its own. In theory, entrance examinations had made administration the preserve of China’s best and brightest since Han times, but in practice aristocratic families always managed to turn high office into a perk of birth. In the seventh century, however, exam scores really did become the only criterion for success. So long as we assume (as most people did) that composing poetry and quoting classical literature are the best guides to administrative talent, China can fairly be said to have developed

the most rational selection processes for state service known to history.

*

As the old aristocracy’s grip on high office slowly loosened, administrative appointments became the surest path to wealth and influence for the gentry, and competition to get into the civil service stiffened. In some years fewer than one candidate in a hundred passed the exams, and stories both sad and comical abound of men retaking the tests for decades. Ambitious families hired tutors, much as they do nowadays to get their teenagers through the exams that winnow out applicants to the most-sought-after universities, and the newly invented printing presses churned out thousands of books of practice questions. Some candidates wore “cheat shirts” with model essays written in the lining. Because grades depended so heavily on literary composition, every young man in a hurry became a poet; and with so many fine minds versifying, this became the golden age of Chinese literature.

The exams created unprecedented social mobility within the educated elite, and some historians even speak of the rise of a kind of “protofeminism” as the new openness expanded to gender relations. We should not exaggerate this trend; the advice to women in

The Family Instructions of the Grandfather

, one of the commonest surviving eighth-century books, would have shocked no one a thousand years earlier—

A bride serves

her husband

Just as she served her father.

Her voice should not be heard

Nor her body or shadow seen.

With her husband’s father and elder brothers

She has no conversation.