Why the West Rules--For Now (80 page)

Read Why the West Rules--For Now Online

Authors: Ian Morris

Tags: #History, #Modern, #General, #Business & Economics, #International, #Economics

Back in Britain, technology jumped from industry to industry, stimulating yet more technology. The most important leap was to ironworking, the industry that made the materials that other new industries used. Britain’s ironmasters had known how to smelt iron with coke since 1709 (seven centuries behind Chinese metallurgists), but had trouble keeping their furnaces hot enough for coke smelting. After 1776 Boulton and Watt’s engines solved the problem by providing steady blasts of air, and within a decade Cort’s puddling-and-rolling process (as wonderfully named as anything in cotton spinning) smoothed out the remaining technical difficulties. Following the same path as cotton, ironmakers saw labor costs plummet while employment, productivity, and profits exploded.

Boulton and his competitors had taken the lid off energy capture. Even though their revolution took several decades to unfold (in 1800, British manufacturers still generated three times as much power from waterwheels as from steam engines), it was nonetheless the biggest and fastest transformation in the entire history of the world. In three generations technological change shattered the hard ceiling. By 1870, Britain’s steam engines generated 4 million horsepower, equivalent to the work of 40 million men, who—if industry had still depended on muscles—would have eaten more than three times Britain’s entire wheat output. Fossil fuel made the impossible possible.

THE GREAT DIVERGENCE

Locals like to call my hometown, Stoke-on-Trent in the English Midlands, the cradle of the industrial revolution. Its great claim to fame comes from being the heart of the Potteries, where Josiah Wedgwood mechanized vase-making in the 1760s. Industrial-scale potting pervaded everything in Stoke. Even my own earliest archaeological experiences as a teenager nearly two centuries later went on in Wedgwood’s shadow, working on misfired pots from a vast dump behind the Whieldon factory where Wedgwood had learned his craft.

Stoke was built on coal, iron, and clay, and when I was young most of its workingmen still got up before dawn and headed for the pit, steelworks, or potbank. My grandfather was a steelworker; my father left school for the mines just before his fourteenth birthday. In my own schooldays we were constantly told how the pluck, grit, and ingenuity of our forebears had made Britain great and changed the world. But so far as I remember, no one told us why it was

our

hills and valleys, rather than someone else’s in some other place, that had cradled the infant industry.

This question, though, is the front line in arguments over the great divergence between West and East. Was it inevitable that the industrial revolution would happen in Britain (in and around Stoke-on-Trent, in fact) rather than somewhere else in the West? If not, was it inevitable that it would happen in the West rather than somewhere else? Or—for that matter—that it would happen at all?

I grumbled in the introduction to this book that even though these questions are really about whether Western dominance was locked in in the distant past, experts offering answers rarely look back more than four or five hundred years. I hope I have made my point by now that putting the industrial revolution into the long historical perspective sketched in the first nine chapters of this book will provide better answers.

The industrial revolution was unique in how much and how fast it drove up social development, but otherwise it was very like all the upswings in earlier history. Like all those earlier episodes of (relatively) rapidly rising development, it happened in an area that had until recently been rather peripheral to the main story. Since the origins of

agriculture, the major cores had expanded through various combinations of colonization and imitation, with populations on the peripheries adopting what worked in the core and sometimes adapting it to very different environments at the margins. Sometimes this process revealed advantages in backwardness, as when fifth-millennium-

BCE

farmers found that the only way to make a living in Mesopotamia was by irrigation, in the process turning Mesopotamia into a new core; or when cities and states expanded into the Mediterranean Basin in the first millennium

BCE

, developing new patterns of maritime trade; or when northern Chinese farmers fled southward and turned the area beyond the Yangzi into a new rice frontier after 400

CE

.

When the Western core expanded north and west from its Mediterranean heartland in the second millennium

CE

, western Europeans eventually discovered that new maritime technology could turn their geographical isolation, which had long been a source of backwardness, into an advantage. More by accident than design, western Europeans created new kinds of oceanic empires, and as their novel Atlantic economy drove social development up, it presented entirely new challenges.

There was no guarantee that Europeans would meet these challenges; neither the Romans (in the first century

CE

) nor the Song Chinese (in the eleventh) had found a way through the hard ceiling. All the signs were that muscles were the ultimate source of power, that no more than 10–15 percent of people would ever be able to read, that cities and armies could never grow beyond about a million members, and that—consequently—social development could never get past the low forties on the index. But in the eighteenth century Westerners brushed these limits aside; by selling power they made mockery of all that had gone before.

Western Europeans succeeded where the Romans and Song failed because three things had changed. First, technology had gone on accumulating. Some skills were lost each time social development collapsed, but most were not, and over the centuries new ones were added. The same-river-twice principle thus kept working: each society that pressed against the hard ceiling between the first century and the eighteenth was different from its predecessors. Each knew and could do more than those that had gone before.

Second, in large part because technology had accumulated, agrarian empires now had effective guns, allowing the Romanovs and Qing

to close the steppe highway. Consequently, when social development pressed against the hard ceiling in the seventeenth century, the fifth horseman of the apocalypse—migration—did not ride. It was a struggle, but the cores managed to cope with the other four horsemen and averted collapse. Without this change, the eighteenth century might have been as disastrous as the third and thirteenth.

Third, again largely because technology had accumulated, ships could now sail almost anywhere they wanted, allowing western Europeans to create an Atlantic economy unlike anything seen before. Neither the Romans nor the Song had been in a position to build such a vast engine of commercial growth, so neither had had to confront the kinds of problems that forced themselves on western Europeans’ attention in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Newton, Watt, and their colleagues were probably no more brilliant than Cicero, Shen Kuo, and theirs; they just thought about different things.

Eighteenth-century western Europe was better placed than any earlier society to annihilate the hard ceiling; within western Europe, the northwest—with its weaker kings and freer merchants—was better placed than the southwest; and within the northwest, Britain was best placed of all. By 1770 Britain not only had higher wages, more coal, stronger finance, and arguably more open institutions (for middle-and upper-class men, anyway) than anyone else, but—thanks to coming out on top in its wars with the Dutch and French—it also had more colonies, trade, and warships.

It was easier to have an industrial revolution in Britain than anywhere else, but Britain still had no lock-in on industrialization. If—as could easily have happened—it had been French bells, not British, that were worn threadbare by ringing victories in 1759, and if France had stripped Britain of its navy, colonies, and trade rather than Britain stripping France, my elders would not have reared me on stories of how Stoke-on-Trent had midwifed the industrial revolution. The elders in some equally smoke-blackened French city such as Lille might have been spinning that yarn instead. France, after all, had plenty of inventors and entrepreneurs, and even a small shift in national endowments or the decisions of kings and generals might have made a big difference.

Great men, bungling idiots, and dumb luck had a lot to do with why the industrial revolution was British rather than French, but they had

much less to do with why the West had an industrial revolution in the first place. To explain that, we have to look at larger forces, because once enough technology had accumulated, once the steppe highway had closed, and once the oceanic highways had opened—by, say, 1650 or 1700—it is hard to imagine what could have stopped an industrial revolution from happening

somewhere

in western Europe. If France or the Low Countries had become the workshop of the world rather than Britain, the industrial revolution might have broken more slowly, perhaps beginning in the 1870s rather than the 1770s. The world we live in today would be different, but western Europe would still have had the original industrial revolution and the West would still rule. I would still be writing this book, but it might be in French rather than English.

Unless, that is, the East had independently industrialized first. Could that have happened if Western industrialization had been slower? Here, of course, I am piling what-ifs on top of what-ifs, but I think the answer is still fairly clear: probably not. Even though Eastern and Western social development scores were neck-and-neck until 1800, there are few signs that the East, if left alone, was moving toward industrialization fast enough to have begun its own takeoff during the nineteenth century.

The East had large markets and intense trade, but these did not work like the West’s Atlantic economy, and while ordinary people in the East were not as poor as Adam Smith claimed in his

Wealth of Nations

(“

The poverty

of the lower ranks of people in China far surpasses that of the most beggarly nations in Europe”),

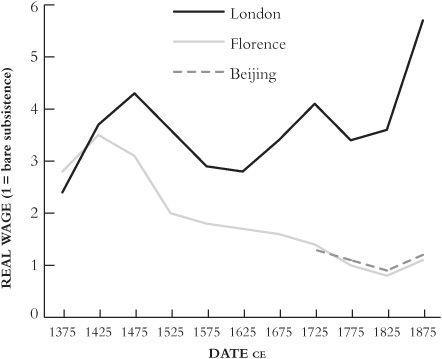

Figure 10.3

shows that they were not rich either. Beijingers

*

were no worse off than Florentines but much worse off than Londoners. With labor so cheap in China and Japan (and southern Europe), the incentives for the local equivalents of Boulton to invest in machinery were weak. As late as 1880 the up-front costs to open a mine with six hundred Chinese laborers were estimated as $4,272—roughly the price of a single steam pump. Even when they had the option, savvy Chinese investors often preferred cheap muscles to expensive steam.

With so little to gain from tinkering, neither Eastern entrepreneurs nor scholars in the imperial academies showed much interest in boilers

and condensers, let alone jennies, throstles, and puddling. To have had its own industrial revolution, the East would have needed to create some equivalent to the Atlantic economy that could generate higher wages and new challenges, stimulating the whole package of scientific thought, mechanical tinkering, and cheap power.

Figure 10.3. Workers of the world, divide: despite their woes, British workers earned much more than non-British between 1780 and 1830 and did better still after 1830. The graph compares the real wages of the unskilled in London, Florence (fairly typical of southern Europe’s low wages), and Beijing (exemplifying Chinese and Japanese wages).

Again, given time, that might have come to pass. Already in the eighteenth century there was a flourishing Chinese diaspora in Southeast Asia; other things being equal, the kind of geographical interdependence that characterized the Atlantic economy might have emerged in the nineteenth century. But other things were not equal. It took Westerners two hundred years to get from Jamestown to James Watt.

If

the East had been left in splendid isolation,

if

it had moved down the same path as the West across the nineteenth and twentieth centuries toward creating a geographically diversified economy, and

if

it had moved at roughly the same pace as the West, a Chinese Watt or Japanese Boulton might at this very moment be unveiling his first steam engine

in Shanghai or Tokyo. But none of those ifs eventuated, because once the West’s industrial revolution began, it swallowed the world.

THE GRADGRINDS

As late as 1750, the similarities between the Eastern and Western cores were still striking. Both were advanced agrarian economies with complex divisions of labor, extensive trade networks, and growing manufacturing sectors. At both ends of Eurasia rich landowning elites, confident in their order’s stability, traditions, and worth, were masters of all they surveyed. Each elite defended its position with elaborate rules of deference and etiquette, and each consumed and produced culture of great subtlety and refinement. Behind all the obvious differences of style and narration, it is hard not to see a certain kinship between sprawling eighteenth-century novels of manners such as Samuel Richardson’s

Clarissa

and Cao Xueqin’s

Dream of the Red Chamber

.