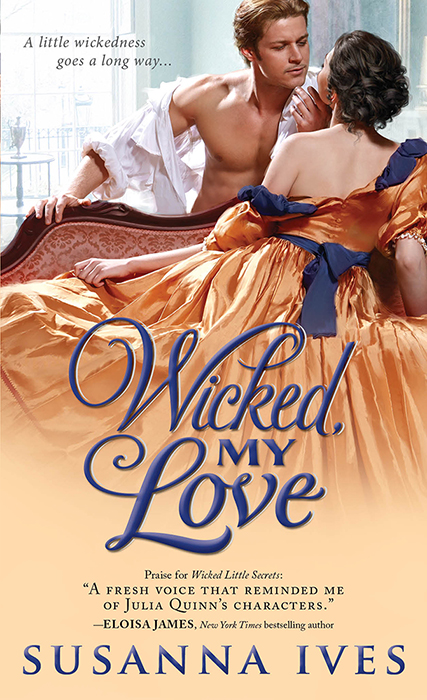

Wicked, My Love

Authors: Susanna Ives

Copyright © 2015 by Susanna Ives

Cover and internal design © 2015 by Sourcebooks, Inc.

Cover art by Anna Kmet

Sourcebooks and the colophon are registered trademarks of Sourcebooks, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systemsâexcept in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviewsâwithout permission in writing from its publisher, Sourcebooks, Inc.

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious or are used fictitiously. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental and not intended by the author.

Published by Sourcebooks Casablanca, an imprint of Sourcebooks, Inc.

P.O. Box 4410, Naperville, Illinois 60567-4410

(630) 961-3900

Fax: (630) 961-2168

Thank you for purchasing this eBook

.

At Sourcebooks we believe one thing:

BOOKS CHANGE LIVES

.

We would love to invite you to receive exclusive rewards. Sign up now for VIP savings, bonus content, early access to new ideas we're developing, and sneak peeks at our hottest titles!

Happy reading

!

To Cathy Leming (w/a Catriona Scott) for your kindness, encouragement, and wonderful insight through the years. My books would not have been born without your help.

1827

Nine-year-old Viscount Randall gazed toward the Lyme Regis coast but didn't see where the glistening water met the vast sky. He was too lost in a vivid daydream of being all grown up, wearing the black robes of the British prime minister, and delivering a blistering piece of oratorical brilliance to Parliament about why perfectly reasonable boys shouldn't be forced to spend their summer holidays with jingle-brained girls.

“You know when your dog rubs against me it's because he wants to make babies,” said Isabella St. Vincent, the most jingled-brained girl of them all, interrupting his musings.

The two children picnicked on a large rock as their fathers roamed about the cliffs, searching for ancient sea creatures. Their papas were new and fast friends, but the offspring were not so bonded, as evidenced by the line of seaweed dividing Randall's side of the rock from hers.

“All male species have the barbaric need to rub against females,” she continued as she spread strawberry preserves on her scone.

She was always blurting out odd things. For instance, yesterday, when he had been concentrating hard on cheating in a game of whist in hopes of finally beating her, she had piped up, “Do you know the interest of the Bank of England rose by a half a percentage?” Or last night, when she caught him in the corridor as he was trying to sneak a hedgehog into her room in revenge for losing every card game to her, including the ones he cheated at. “I'm going to purchase canal stocks instead of consuls with my pin money because at my young age, I can afford greater investment risks,” she'd said, shockingly oblivious to the squirming, prickly creature under his coat.

Despite being exactly one week younger than he was, she towered over him by a good six inches. Her legs were too long for her flat torso. An enormous head bobbled atop her neck. Her pale skin contrasted with her thick, wiry black hair, which shot out in all directions. And if that wasn't peculiar enough, she gazed at the world through lenses so thick that astronomers could spot new planets with them, but she needed them just to see her own hands. Hence, he took great glee in hiding them from her.

“You're so stupid.” He licked fluffy orange cream icing from a slice of cake. “Everyone knows babies come when a woman marries a man, and she lies in bed at night, thinking about yellow daffodils and pink lilies. Then God puts a baby in her belly.” He used an exaggerated patronizing tone befitting a brilliant, powerful viscount destined for prime ministershipâeven if “viscount” was only a courtesy title. Meanwhile, Isabella was merely a scary, retired merchant's daughter whom no one would ever want to marry. And, after all, a female's sole purpose in life was to get married and have children.

“No, you cabbage-headed dolt,” she retorted. “Cousin Judith told me! She said girls shouldn't be ignorant about the matters of life.” Isabella's Irish mother had died, so Cousin Judith was her companion. Randall's mama claimed that Judith was one of those “unnatural sorts” who supported something terrible called “rights of women.” He didn't understand the specifics, except that it would destroy the very fabric of civilized society. He would certainly abolish it when he was prime minister.

“Judith said that for a woman to produce children, she, unfortunately, requires a man.” Isabella's gray eyes grew into huge round circles behind her spectacles. “That he, being of simple, base nature and mind, becomes excited at the mere glimpse of a woman's naked body.”

He was about to interject that she was wrong againâgirls were never rightâbut stopped, intrigued by the

naked

part. Nudity, passing gas, and belching were his favorite subjects.

“Anyway, a man has a penis,” she said. “It's a puny, silly-looking thing that dangles between his limbs.”

He gazed down at the tiny bulge in his trousers. He had never considered his little friend silly.

“When a man sees the bare flesh of a woman, it becomes engorged,” she said. “And he behaves like a primitive ape and wants to insert it into the woman's sacred vagina. My cousin said that was the passage between a woman's legs that leads to the holy chamber of her womb.”

“The what?” Where was this holy chamber? He was suddenly overcome with wild curiosity to see one of these sacred vaginas.

“Judith said the man then moves back and forth in an excited, animalistic fashion for approximately ten seconds, until he reaches an excited state called

orgasm

. Then he ejaculates his seed into the woman's bodily temple, thus making a baby.”

His dreams of future political power, the shimmering ocean, fluffy vanilla-orange icing, and a prank on Isabella involving a dead, stinking fish all seemed unimportant. He gazed at his crotch and then her lapâthe most brilliant idea he ever conceived lighting up his brain. “I'll show you my penis if you show me your vagina.” He flashed his best why-aren't-you-just-an-adorable-little-thing smile, which, when coupled with his blond hair and angelic, bright blue eyes, charmed his nurses into giving him anything he wanted. However, his cherubic looks and charm didn't work on arctic-hearted Isabella.

“You idiot!” She flicked a spoonful of preserves at his face.

“You abnormal, cracked, freakish girl!” he cried. “I only play with you because my father makes me.” He smeared her spectacles with icing. In retaliation, she grabbed her jar of lemonade and doused him.

When their fathers and nurses found them, she was atop the young viscount, now slathered in jam, icing, mustard, and sticky lemonade, pummeling him with her little fists.

Mr. St. Vincent yanked his daughter up.

“She just hit me for no reason,” Randall wailed, adopting his poor-innocent-me sad eyes. “I didn't do anything to her.”

“Young lady, you do not hit boys,” her father admonished. “Especially fine young viscounts. You've embarrassed me again.”

“I'm sorry, Papa,” Isabella cried, distraught under her father's hard gaze. Humiliation wafted from her ungainly body and Randall felt a pang of sympathy, but it didn't diminish the joy of knowing she had gotten in trouble and he hadn't.

The Earl of Hazelwood placed a large hand on the back of Randall's neck and gave his son a shake. “Son, we didn't find any old sea creatures, but Mr. St. Vincent has come up with a brilliant idea to help our tenants and provide a dependable monthly income.” He turned to his friend. “We are starting the Bank of Lord Hazelwood. Mr. St. Vincent and I will be the major shareholders and we will add another board member from the village.”

Even as a small child, Randall had an uneasy, gnawing feeling in his gut about this business venture that none of Mr. St. Vincent's strange terms, such as

financial

stabilization

,

wealth

building

, or

reliable

means

for

tenant

borrowing

and

lending

, could dissuade. He was never going to get rid of that rotten Isabella.

***

Through the years, he and she remained like two hostile countries in an uneasy truce; a lemonade-throwing, cake-splatting war could break out at any moment. Randall would indeed follow his path to political fame, winning a seat in Parliament after receiving a Bachelor of Arts from St. John's College, Cambridge. He basked in the adoration of London society as the Tory golden boy. To support Randall's London lifestyle, the Earl of Hazelwood signed over a large amount of the bank's now quite profitable shares to his son.

He came home from Parliament when he was twenty-three to witness Isabella standing stoic and haunted with no black veil to hide her pale face from the frigid January air as they lowered her father into the frozen earth. Having no husband, she inherited her father's share in the bank and began to help run it. The two enemies' lives would be hopelessly entwined through the institution born that fateful day in Lyme Regis, when Randall learned how babies were made.

For the next five years, bank matters rolled along smoothly. Then the board secretary passed away unexpectedly, leaving his portion to his young bachelor nephew, Mr. Anthony Powers.

That's when all manner of hell broke loose.

1847

Stuke Buzzard, England

Isabella lifted a delicate, perfectly coiled t

endri

l of hair in the “luxurious shade of raven's wing” from the Madam O'Amor's House of Beauty package that she had secreted into her bedchamber.

Her black cat, Milton, who had been bathing his male feline parts on her pillow, stopped and stared at the creation, his green eyes glittery.

“This is not a rat,” Isabella told him. “You may not eat it.”

Unconvinced, the cat rolled onto his paws, hunched, and flicked his tail, ready to pounce.

The advertisement in last month's

Miroir

de

Dames

had read

“Losing your petals? Withering on the vine? Return to your full, fresh, feminine bloom with Madam O'Amor's famous youth-restoring lotion compounded of the finest secret ingredients, and flowing tendrils, puffs, and braids made from the softest hair.”

Isabella typically didn't believe such flapdoodle. But at twenty-nine, she was dangling off the marital cliff and gazing down into the deep abyss of childless spinsterhood. Now she finally had a live, respectable fish by the name of Mr. Powers, her bank partner, swimming around the hook. After he walked her home from church on Sunday, she had decided not to take any chances and had broken down and ordered Madam's concoctions. Even then, a little voice inside her warned, “Don't lie to yourself. Who would want to marry an abnormal, cracked, freakish girl?” All those things Randall had called her years ago. Strange that words uttered so long ago still had the power to sting.

After making excuses to loiter about the village post office for almost a week, Isabella had been relieved when her order had finally arrived on the train that morning, just in time to restore her full, fresh, feminine bloom before Mr. Powers called on bank business. Little did the poor gentleman know that for once she couldn't care less about stocks and consuls. She was hoping for a more personal investment with a high rate of marital return: a husband.

Standing before her vanity mirror, she opened the drawer, drew out a hairpin, and headed into battle. Her overgrown, irrepressible mane refused to curl tamely, held a fierce vendetta against pins, and rebelled against any empire, Neapolitan, or shepherdess coiffure enforced on it. She secured the first tendril and studied the result. It didn't fall in the same easy, elegant spiral as in the advertisement, but shot out from behind her ear like a coiled, bouncy spring.

“Oh no, this looks terrible.” She tugged at it, trying to loosen the curl. “I'll just secure the other. You can't tell from just one; it's not balanced.”

Meanwhile, her cat eyed her, scheming to get at those strange yet oddly luxurious rats on her head.

The second tendril was no better than the first. “I look even more abnormal, cracked, and freakish, if that were possible. I knew this was a stupid idea. Why did I even try when I knew it was stupid?” She sank into her chair and buried her face in her hands. She just wanted a husband and children. Why was it so difficult for her? Why couldn't she be like her motherâgraceful and gentle?

Tap,

tap.

“Darling, I hate to nag,” Judith called through the door. “But the Wollstonecraft Society meeting is in less than two weeks. You really must practice

your speech.”

Oh

fudge!

Isabella didn't have time to remove the offending curls. She grabbed Madam O'Amor's box and shoved it under the bed. Milton, who was teetering on the edge of the mattress, saw his moment and took a nasty swipe at her head.

Judith, founding member of the Mary Wollstonecraft Society Against the Injurious Treatment of Women Whose Rights Have Been Unjustly Usurped by the Tyrannical and Ignorant Regime of the Male Kind, strolled in. Her auburn hair was pulled into a sloppy bun and secured by crossed pencils, her reading glasses sitting low on her Roman nose. Before her face, she held Isabella's draft of her acceptance speech for this year's Wollstonecraft award.

“My dear, this is interesting information, but it's rather, wellâ¦boring,” she said. “Unlike you, most people don't remember numbers andâmy goodness, what torture have you inflicted on your poor hair?”

Isabella extricated Milton's claw from her head and drew herself tall. “I've styled my hair into tendrils,” she said firmly. Her companion was bossy and a relentless nagger. Isabella had to put up a strong front.

“Tentacles?”

“I said

tendrils

.”

A tiny pleat formed between Judith's eyebrows. “I hope you aren't doing all this for a

man

?” Her face screwed up tight, as if the word

man

emitted a

foul stench.

“No, no, of course not.” Isabella had been careful to hide her little infatuation with Mr. Powers. If she didn't, Judith would launch into her standard marital lecture, that Isabella shouldn't give over her freedom and money to a simple-minded, barbaric man who would just gamble away her wealth. “W-what would I do with a man?” Isabella laughed nervously, trying to sound innocent. Her gaze wandered to the bed, and her mind lit up with all manner of things she would do with him.

Thankfully, Judith didn't pursue the subject, but reverted back to her usual obsession: the Wollstonecraft Society. “Now, darling, you need to make an emotional connection with the society members in your speech. You must speak to their desires and pains. Remember how we discussed showing our emotions when writing your book.”

Isabella groaned. “We agreed never to talk about the book again.”

A fellow member of the Wollstonecraft Society had recently bought a printing press in London. Judith had thought it a wonderful idea for Isabella to write a volume educating women about investing and the stock exchange. She'd pestered Isabella for months. Finally, when the weather turned brutal in the winter, Isabella produced a work she titled

A

Guide

to

the

Funds

and

Sound

Business

Practices

for

Gentle

Spinsters

and

Widows

by “A Lady.” She gave the pages to Judith to edit and happily forgot about it. Three months later, her companion returned a bound book retitled

From

Poor

to

Prosperous, How Intelligent, Resourceful Spinsters, Widows, and Female Victims of Ill-fated Marital Circumstances Can Procure Wealth, Independence, and Dignity

by Isabella St. Vincent, majority partner in the Bank of Lord Hazelwood.

The entire village must have heard Isabella's mortified scream. To make it all the worse, Judith had taken her modest examples, such as “Hannah was a plain spinster with only the limited means left to her by her late father,” and added such Gothic claptrap as Hannah having been used and abandoned by some arrogant lord of a manor.

She had hoped the book would languish unread on some library bookshelf until it disintegrated into dust, but it was now in its fourth printing. And Isabella, who was only a member of the society because Judith sent in her membership letter each year, was to be awarded the society's highest honor: the Wollstonecraftâa large gold-painted plaster bust of the famous advocate of rights for women.

Judith pointed to a paragraph on page two of Isabella's scribbled speech. “Now, where you say consuls return three percent, you should perhaps say, âan infirm widow whose husband, a typical subjugating, evil man, had gambled away their savings before drinking himself toâ'”

“I can't say those things.” Isabella flung up her arms. “You know I'm a horrid lecturer. I just stand there mute or start babbling nonsense. Please go to the London meeting and accept the award. You had as much to do with the book as I. And you know Milton gets mad when I go away, and wets my bed out of spite.”

“Isabella!” Judith gasped. “It's the Wollstonecraft! Do you know how many ladies dream of being in your shoes?”

Isabella couldn't think of more than six. “Butâ¦but⦔

I've almost got one of those subjugating, evil men hooked and squirming on my marital line. I can't leave now. To Hades with the gold bust of Mary Wollstonecraft! If I don't know a man soon, I'm going to spontaneously combust.

“No

buts

,” her companion said, handing Isabella back her pages. Surrounding her neat, efficient words and tables were arrows pointing to her cousin's scrawled notes that read “Young widow must support ailing child,” or “Honorable, aging spinster turned away from her home.”

“This is wrong. Investing is about numbers, not whether you are abandoned or caring for your dead sister's husband's cousin's eleven blind and crippled orphaned children or such nonsense.”

“Now you sound like a

man

.” Judith scrunched her nose again at the terrible

M

word. “The women of Britain need your help. They have no rights, no vote, no control over their lives. Money is their only freedom.” She placed her palm on Isabella's cheek. “I know what a brave, kind soul you are. Inside of you remains the grave child who didn't cry by her mother's casket and the young woman who waited stoically every day by her dying father's bedside. Don't be afraid of your vulnerability and pain. Use it to talk to your sisters in need.”

Isabella's throat turned dry. Judith didn't know what she was talking about. Emotions were wild and confusing variables. Their unpredictability scared Isabella, making her feel like that helpless child unable to stop her mama from dying. Logic was, well, logical. It had numbers, lines, formulas, and probabilities. If she could teach those ladies anything, it would be that the key to good investments was to discard those useless, confounding emotions that only muddied the issues and look at the cold, hard patterns in the numbers.

“I knew from the earliest moments of our acquaintance that you would grow into a brilliant leader of women,” Judith continued. “Now you must go to London and accept your calling.” She turned and sat in the chair by the grate. “Let's rehearse. So chin up, shoulders straight, and begin.”

Isabella stared down at the pages and began to drone, “Thank you, ladies of theâ”

Mary, one of the servants, slipped through the door.

Mr. Powers is here!

“Pardon me,” Mary said with a bob of a curtsy. “Lord Randall has called.”

“Lord Randall,” Isabella said, disappointed. “What is he doing here? Isn't his parents' annual house party starting today? Oh bother. Put him in the library.” At least she could use the loathsome viscount as an excuse to escape this oratorical torture. “I'm sure this is about extremely urgent bank business that needs attending to immediately,” she told Judith.

***

After the last session of Parliament, what Lord Randall, the House of Commons' famed Tory orator, needed to fortify himself was twelve uninterrupted hours in bed with a lovely lady before heading home to his parents' annual house party and shackling himself to a powerful Tory daughter, living unhappily, but politically connected, ever after.

If things had gone as planned, at this very moment he might have been leisurely arriving on the train after one last good morning tumble.

Of course, things hadn't gone as planned, as they hadn't for the last six months. Instead of feeling the soft curves of a stunning little ballet dancer or actress, he had felt the bump and rumble of a train as he traveled alone through the night, staring at the blackness beyond the window, his mind swirling with scenarios of political ruin. Now he stood in the library of a woman he was desperate to see. But hell and damnation, he would rather gnaw off his own leg than share twelve uninterrupted hours of frolicking with Isabella.

He raked his hands through his hair, feeling little strands come loose.

Great

. On top of everything, he was losing his hair.

Could

something

else

go

wrong?

And

where

is

she?

He paced up and down the Aubusson rug adorning her somber, paneled library. Some books lined the shelves, but mostly financial journals in leather boxes labeled by date and volume. A large oak desk was situated between two massive arched windows, its surface clean except for a lamp and inkwell. He tugged at his cravat as if he were choking. How could Isabella live in such oppressive, silent order? It stifled his soul.

He strode to one of the windows and watched the line of carriages and flies from the railroad station heading up the hill to his father's estate. Inside them rode Tories of the “right kind” as his mother had phrased it, along with their daughters, all vying for Randall's hand in marriage. He leaned his head against the glass. “You've got to save me, Isabella,” he whispered.

“I'm surprised to see you,” he heard that familiar soprano voice say behind him.

An odd, warm comfort washed over him at the sound. He turned and found himself gazing at the fashion tragedy that was Isabella. She wore a dull blue dress or robe or something that made a slight indentation around the waist area and concealed everything else from her chin to the floor. Her glasses magnified her gray eyes, and she had styled her wild hair in some new, odd, dangly arrangement. Still, a peace bloomed in his chest at the sight of her frumpy dishevelment, like that nostalgic, grounding feeling of coming home. Well, not his real home, where, despite all British rules to the contrary, his strident mother ruled. As the rest of his world was coming undone, Isabella remained the same old ungainly girl of his memoryâhis faithful adversary.

“Just âI'm surprised to see you'?” he repeated in feigned offense. “Perhaps âGood morning, Lord Randall. I've missed you terribly. You haunt my dreams. I'm enamored of your dazzling intellectual and manly powers. There is a void in my tiny, black heart that only you can fill.'” His anxiety started to ease as he settled into the thrust, glissade, and parry of their typical conversation.