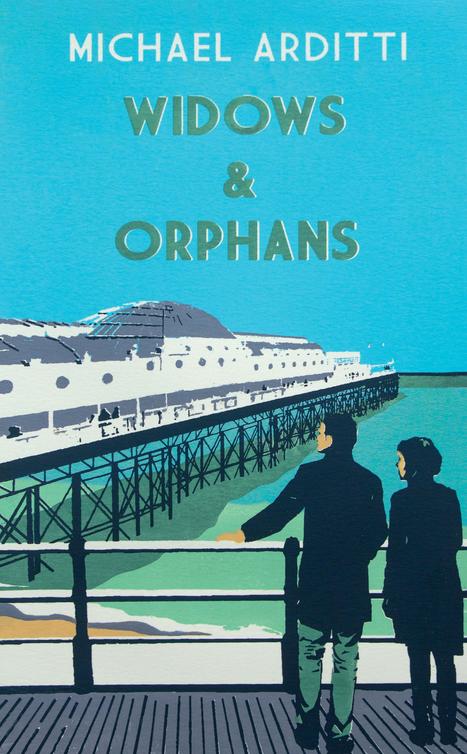

Widows & Orphans

Authors: Michael Arditti

a novel by

MICHAEL ARDITTI

For three friends and colleagues:

Clare Colvin, Jane Mays and Ruth Leon

‘Be kind, for everyone you meet is fighting a hard battle’

Philo of Alexandria (Attrib.)

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- One

- Francombe Pier Inferno

- Two

- Mystery Poisoning

- Three

- Disturbing Incidents at Nature Reserve

- Four

- Charlie is Our Darling

- Five

- The Poison in Our Society

- Six

- ‘Notes from the Pulpit’

- Seven

- £3,260 raised in

Mercury

Christmas Toy Appeal - Eight

- Pier Proprietor Honoured

- Nine

- Well-loved Editor Retires

- Ten

- Your

New Mercury - Acknowledgements

- By the Same Author

- Copyright

F

rancombe watched in horror on Monday night as a sea of flames swept through its historic pier, reducing much of the 980 foot structure to ashes and rubble.

For ten hours, seventy firemen and eight fire engines battled the blaze, their rescue efforts hampered by high winds and poor visibility. Roads were closed and nearby residents advised to keep their windows shut.

Sam Vernham, chief fire officer of Sussex Fire and Rescue Service, confirmed that the cause of the fire had yet to be established. ‘Full investigation must wait until structural engineers give us the go-ahead. Meanwhile, I urge people not to speculate, which will only cause more distress to those affected.’

This is the latest in a string of disasters to hit the 144-year-old pier. An earlier fire in June 2000 destroyed the Moorish pavilion. The pier itself was closed to the general public in June 2008, after two of its support columns were found to be in imminent danger of collapse.

In March 2009, a Save Our Pier petition, organised by the

Mercury

, attracted over 15,000 signatures and, in May 2011, Francombe Borough Council finally approved the com+pulsory purchase of the Grade II listed building from its Panamanian-based owners, Rockingham Securities. Last May, the Council narrowly voted to sell the pier to Weedon Investments, owned by controversial local entrepreneur, Geoffrey Weedon, whose plans for it have yet to be disclosed.

After surveying the devastation, Glynis Kingswood, Chair of the Francombe Pier Trust, declared: ‘This is a tragedy. The pier is Francombe and Francombe is the pier. We must all work together to rebuild this unique piece of our heritage.’

Of all the campaigns Duncan had launched in nearly thirty years at the helm of the

Mercury

, the one to secure the future of the pier remained closest to his heart. After three years during which the structure had been left to rot, the paper had set up the Save Our Pier petition, attracting the signatures of almost a fifth of Francombe’s residents; given away 10,000 stickers that had been plastered on windows, windscreens, walls and the Diamond Jubilee statue of Queen Victoria; and organised a Day of Protest in September 2009, which saw more than 2,000 people march on the Town Hall to demand that the Council take immediate action to purchase the pier from its absentee owners.

The march, extensively reported in the national media, achieved its objective. After a further two years of legal wrangling and a costly programme of emergency repairs, the Council assumed control of the pier. Meanwhile, the Francombe Pier Trust was established with the aim of restoring and running the pier as a viable local concern; but, although the Trust was awarded an £85,000 feasibility grant by English Heritage to conduct a structural survey and draw up architectural plans, it failed to obtain capital funding from either the Heritage Lottery or the EU. This bitter blow was compounded in May 2013 when the Council announced that, in view of both the Trust’s inability to raise finance and the assessors’ estimate that a sum in excess of £25,000,000 would be needed to repair the fabric, plus a similar amount to resume operation, it had agreed to sell the pier to Weedon Investments. Duncan, who attacked the decision in a series of hard-hitting editorials, had never given up hope that the sale might be revoked – until the fire.

For Duncan, the pier had always been the best of Francombe. At school, his home town had been derided by boys who, if they holidayed in England at all, headed for the more refined reaches of Cornwall and Suffolk. Even in its Victorian heyday, it had never enjoyed the prestige of its neighbouring

resorts. While Brighton, Eastbourne and Worthing attracted the affluent middle classes, Francombe catered to ‘clerks and other working people’ from London’s East End. By the 1960s, any lingering claims to gentility had been abandoned in a welter of binge drinking and gang warfare. But amid the bug-infested guesthouses, grimy pubs, litter-strewn beaches and vomit-splattered pavements, one monument remained unsullied. From the octagonal tollbooths and glass-covered Winter Garden to the multi-domed pavilion and horseshoe arcade, the pier stood comparison with any in the country.

The midget photographer with the monkey that never blinked; the gypsy fortune teller with the aniseed-scented booth; the sad-faced silhouettist with scissors as adept as a brush; the flea circus boasting ‘the smallest big top in the world’: these formed the pattern of Duncan’s childhood memories, as they did for so many in Francombe. Then in 1969 when he was five years old, there was the unforgettable celebration of the

Mercury

’s centenary. His father hired the pavilion for a banquet attended by his entire staff, past and present, and a host of local luminaries. Duncan, pledged to be on his best behaviour, sat rigidly through the profusion of speeches, disgracing himself only once when he asked in a piercing whisper why the Mayor was wearing a necklace. He danced with his mother, his sister Alison and, as she had never ceased to remind him, his father’s young secretary, Sheila. He watched the fireworks, which magically spelt out

Mercury

and

100 Years

across the night sky. Then, lulled by the swash of the waves against the columns, he fell fast asleep.

Emerging from his reverie with an acute sense of loss, Duncan was tempted to approve the dummy front page with its one-word headline, ‘Gutted’, above a photograph of the pier head smothered in smoke and looking eerily like St Paul’s at the height of the Blitz, but he shied away from the twin offences of sensationalism and sentimentality. Now, more than ever, he was determined to stick to the standards

for which the paper was known – and, in some quarters, ridiculed. So, having settled on the more sober ‘Francombe Pier Inferno’, he signed off the page and put the paper to bed.

He walked into the reporters’ room, which as ever contrived to look both cluttered and depleted. Despite the eight empty desks, Ken, the news editor, sat facing his two reporters, Rowena and Brian, at a single desk in the centre, with Stewart, the sub, and Jake, the sports editor, at desks on either side. While Stewart’s was obsessively neat, with even the pens in his tray graded according to size, the others were in varying states of chaos. Files, books and papers were scattered across every surface, along with a hairbrush, make-up bag and headache pills (Rowena), an electric-blue T-shirt and large tub of protein powder (Brian) and, ominously, a spike full of invoices (Ken). Although Mary, the cleaner, made sporadic raids on the news desk, Jake had berated her so often for disturbing his filing system that she had given up on sport, with the result that two half-eaten pizzas rested on a pile of football programmes as if he were preparing a feature on botulism at the ground rather than analysing Francombe FC’s prospects for the new season. Four ancient computer monitors gathered dust beside the packed bookshelves. Slumped over one was Humphrey, a giant teddy bear who had been left unclaimed after a competition and adopted as the office mascot. Much prized for his soothing presence, he was regularly called on to mediate in staff disputes. Whatever layers of irony had once informed Rowena’s

You don’t have to be mad to work here but it helps

poster had long been worn away.

Although he lacked his father’s easy conviviality, Duncan prided himself on running a close-knit team. Foremost among them was Ken, not only the paper’s news editor but his deputy, a role that had been nominal for the past three years during which he had not taken a single day’s holiday or sick leave. Having, in his own words, ‘fallen in love with journalism’ on his paper round, Ken had been hired as a junior

reporter straight from school in 1970. His starting salary was £6 a week, of which he paid £2 to his mother for his keep, £1 on travel, and 30 shillings to the retired secretary who taught him shorthand and typing; sums that seemed as comical to the generations of juniors to whom he described them as did his lifelong dedication to the paper itself. Unlike them, he had never seen the

Mercury

as a stepping stone to Fleet Street but remained passionately committed to a strong and crusading local press. He had kept the faith for more than four decades, but in recent years it had been severely tested, first by the paper’s relentless struggle to survive and then by his only daughter’s death. In the one human-interest story he chose not to write, he had donated a kidney to her, which her body rejected. ‘It’s a good thing it wasn’t his liver,’ Rowena had said when she found him drunk at his desk.

Rowena herself had been with the paper on and off for almost twenty years, the ‘off’ being the three years she spent at home after her daughter was born: the daughter who, on her parents’ acrimonious divorce, had elected to live with her father, a move that Rowena imputed solely to his greater spending power. This in turn fuelled her resentment of the editor-proprietor who consistently undervalued her. She was forty-five years old, a fact that Duncan acknowledged guiltily, given her objections to the frequency with which women’s ages were printed in the paper compared to men’s. Since her divorce, she had been reluctant to cover anything that might be considered women’s issues, be they jumble sales, zumba classes or multiple births. Meanwhile, she relished every chance, however inopportune, to highlight male hypocrisy, as in a recent piece on a golden wedding when she caustically pointed out that the husband’s claim of not having looked at another woman for fifty years had been ‘flatly contradicted when he fondled my bottom as he showed me out’. She then turned her fire on her male subeditor when the line was cut.

Stewart, the subeditor in question, had been at the paper

almost as long as Rowena, although he could not blame his lack of advancement on the demands of childcare when it was the absence of children that had blighted his life. Having struggled for years, first with the stresses of IVF and then with the hormonal changes that the treatment produced in his wife, Gillian, he had finally left her for Laura who, as fate would have it, also failed to conceive. Their hopes of adoption were dashed by Gillian’s damning testimonial. In company he made light of it, citing their greater disposable income, but in private he dropped his guard; Duncan had found him in tears over the story of a woman and her three young children burnt to death by a fallen candle after their electricity was cut off. His emotions were heightened by having to check copy, devise headlines and input pictures for the entire paper. The increased pressure led to errors, such as the once exemplary

Mercury

printing a photograph of the new Lady Mayoress under the caption ‘Mystery Beast Spotted in the Woods’, eliciting furious protests from the Town Hall.

Like Stewart, Jake had joined the paper as one of a department of three but, unlike Stewart, he relished the chance to run it single-handed. Duncan, whose involvement in sport had ended when he left school and whose interest in it waned after Alison retired from professional tennis, was happy to cede responsibility for the four back pages to a man who was a passionate enthusiast for every kind of game except cricket, for which he displayed such aversion that he insisted on covering it under a pseudonym. A classic armchair enthusiast, Jake was large and lumbering, the balls of paper around the bin a token of his ineptitude. During his first years at the

Mercury

he lived with his mother, who sent him to work every day with a packet of fish-paste sandwiches. When she died following a massive stroke, he discovered that she had changed her will, leaving her house to the long-estranged sister who had come to nurse her three months before. Duncan was one of many who urged him to contest the will but he refused, preferring to

rent a room from an elderly widow, who cooked and cleaned for him, and even made him fish-paste sandwiches. On evenings when he wasn’t at work and she at bingo, they watched television together. Duncan, who had dinner with his mother twice a week, found their domesticity a threat. Brian, on the other hand, claimed that they were conducting a torrid affair. ‘You’re a gerontophile,’ he said, with all the relish of one who had just learnt the word.

Jake’s pained expression made it clear that the idea of such an affair (or, indeed, of any affair) had never occurred to him. ‘What do they teach you at school these days?’ he asked.

This was a question that had long exercised Duncan in respect of his youngest member of staff. Like Ken, Brian had joined the

Mercury

straight from school, but the intervening four decades had given him a very different outlook. In his three years at the paper he had shown both a genuine desire to learn and a tacit contempt for his teachers. It was impossible to fault either his commitment or his work. Despite the lurid tales of his nightly exploits, which Duncan suspected revealed a talent for fiction as much as for reportage, he was at his desk by 8.30 each morning. He embarked on every assignment that Ken gave him, from Council meetings to ‘death knocks’, with the same enthusiasm that he did his various dates, insisting on the need for experience before he respectively specialised and settled down. He was the one writer who never complained of the extra work involved in maintaining the website (while regularly complaining of the flaws in the site itself). His confusion of brashness with charm would land him in trouble should he ever secure the Fleet Street job he so desperately craved.

While the rest of the staff laughed off Brian’s posturing, Sheila took it seriously. Too shrewd not to realise that his deference was a form of mockery, she nonetheless succumbed to it, responding with a skittishness that only incited him further. Her repeated claim that ‘I’m old enough to be your

mother’ was particularly unfortunate, given his calculation that she was old enough to be his grandmother, or even his great-grandmother had she followed the Francombe trend for underage pregnancy. Sheila had joined the staff in 1967 as Duncan’s father’s secretary. Even Duncan, who had known her all his life, found it hard to credit that, along with her shorthand and typing speeds, her chief assets had been her breezy manner and infectious laugh. He could not help equating Sheila’s faded appeal with that of the paper itself. When he restructured the company on his father’s death, Duncan had promoted her to office manager, which, as she wryly remarked, combined her former responsibilities with those of receptionist, administrator and general dogsbody.