William Shakespeare: The Complete Works 2nd Edition (11 page)

Read William Shakespeare: The Complete Works 2nd Edition Online

Authors: William Shakespeare

Tags: #Drama, #Literary Criticism, #Shakespeare

BOOK: William Shakespeare: The Complete Works 2nd Edition

11.11Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

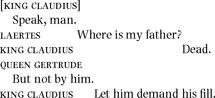

Line variations

thou

AND

you

Many special effects are achieved by departing from metrical norms - making lines longer or shorter than usual, juxtaposing different kinds of feet, or breaking lines in unexpected places. Short lines provide an important type of example. Whether these are introduced by an editorial or an authorial eye, there is always a semantic or pragmatic effect which needs to be carefully assessed. The short line, for example, is often used to mark a significant moment in a speech, especially a pointed contrast, as in this example from

Othello

(1.3.391-4):

Othello

(1.3.391-4):

The Moor is of a free and open nature,

That thinks men honest that but seem to be so,

And will as tenderly be led by th’ nose

As asses are.

Lines of five feet normally express three or four semantically specific points. In this example, the first two lines each contain four lexical items (

Moor, free, open, nature; think, man, honest, seem

), and the third has three (

tenderly, lead, nose

). By contrast, the semantic content of the fourth line is a single lexical item (

ass

), which now has to fill a semantic ‘space’ we normally associate with five feet. Several prosodic means are available to enable an actor to achieve this, such as slowing the tempo and rhythm of the syllables or varying the length of the final pause.

Moor, free, open, nature; think, man, honest, seem

), and the third has three (

tenderly, lead, nose

). By contrast, the semantic content of the fourth line is a single lexical item (

ass

), which now has to fill a semantic ‘space’ we normally associate with five feet. Several prosodic means are available to enable an actor to achieve this, such as slowing the tempo and rhythm of the syllables or varying the length of the final pause.

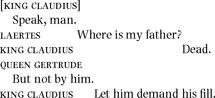

Splitlines - a five-foot line distributed over more than one speaker - must similarly be interpreted in semantic or pragmatic terms. From a semantic point of view, the space of the five-foot line is being filled with more content than is usual. From a prosodic point of view, the more switching between characters, the faster the pace. These factors operate most noticeably in the (rare) cases where a line is split into five interactive units, as in the scene in

King John

(3.3.64-6) when the King intimates to Hubert that Arthur should be killed:

King John

(3.3.64-6) when the King intimates to Hubert that Arthur should be killed:

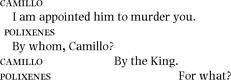

From a pragmatic point of view, there is an immediate increase in the tempo of the interaction, which in turn conveys an increased sense of dramatic moment. On several occasions, the splitlines identify a critical point in the development of the plot, as in this example from

The Winter’s Tale

(1.2.412-13):

The Winter’s Tale

(1.2.412-13):

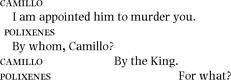

Sometimes, the switching raises the emotional temperature of the interaction. In this

Hamlet

example (4.5.126-7) we see the increased tempo conveying one person’s anger, immediately followed by another person’s anxiety:

Hamlet

example (4.5.126-7) we see the increased tempo conveying one person’s anger, immediately followed by another person’s anxiety:

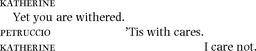

An increase in tempo is also an ideal mechanism for carrying repartee. There are several examples in The

Taming of the Shrew

, when Petruccio and Katherine first meet, as here (2.1.234):

Taming of the Shrew

, when Petruccio and Katherine first meet, as here (2.1.234):

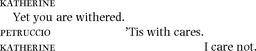

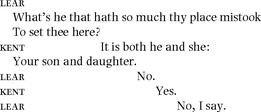

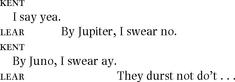

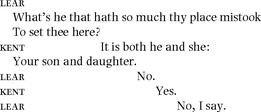

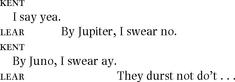

In a sequence like the following (

The Tragedy of King Lear

, 2.2.194-8) there is more than one tempo change:

The Tragedy of King Lear

, 2.2.194-8) there is more than one tempo change:

Here, if we extend the musical analogy, we have a relatively lento two-part exchange, then an allegrissimo four-part exchange, then a two-part allegro, and finally a two-part rallentando, leading into Lear’s next speech. The metrical discipline, in such cases, is doing far more than providing an auditory rhythm: it is motivating the dynamic of the interaction between the characters.

Discourse interactionThe aim of stylistic analysis is ultimately to explain the choices that a person makes, in speaking or writing. If I want to express the thought that ‘I have two loves’ there are many ways in which I can do it, in addition to that particular version. I can alter the sentence structure (

It’s two loves that I have

), the word structure (

I’ve two loves

), the word order (

Two loves I have

), or the vocabulary (

I’ve got two loves, I love two people

), or opt for a more radical rephrasing (

There are two loves in my life

). The choice will be motivated by the user’s sense of the different nuances, emphases, rhythms, and sound patterns carried by the words. In casual usage, little thought will be given to the merits of the alternatives: conveying the ‘gist’ is enough. But in an artistic construct, each linguistic decision counts, for it affects the structure and interpretation of the whole. It is rhythm and emphasis that govern the choice made for the opening line of Sonnet 144: ‘Two loves I have, of comfort and despair’. As the aim is to write a sonnet, it is critical that the choice satisfies the demands of the metre; but there is more to the choice than rhythm, for I have two loves would also work. The inverted word order conveys two other effects: it places the theme of the poem in the forefront of our attention, and it gives the line a semantic balance, locating the specific words at the beginning and the end.

It’s two loves that I have

), the word structure (

I’ve two loves

), the word order (

Two loves I have

), or the vocabulary (

I’ve got two loves, I love two people

), or opt for a more radical rephrasing (

There are two loves in my life

). The choice will be motivated by the user’s sense of the different nuances, emphases, rhythms, and sound patterns carried by the words. In casual usage, little thought will be given to the merits of the alternatives: conveying the ‘gist’ is enough. But in an artistic construct, each linguistic decision counts, for it affects the structure and interpretation of the whole. It is rhythm and emphasis that govern the choice made for the opening line of Sonnet 144: ‘Two loves I have, of comfort and despair’. As the aim is to write a sonnet, it is critical that the choice satisfies the demands of the metre; but there is more to the choice than rhythm, for I have two loves would also work. The inverted word order conveys two other effects: it places the theme of the poem in the forefront of our attention, and it gives the line a semantic balance, locating the specific words at the beginning and the end.

Evaluating the literary or dramatic impact of the effects conveyed by the various alternatives can take up many hours of discussion; but the first step in stylistic analysis is to establish what those effects are. The clearest answers emerge when there is a frequent and perceptible contrast between pairs of options, and this is the best way of approaching the analysis of discourse interaction in the plays. Examples include the choice between the pronouns thou and you and the choice between verse and prose.

THE CHOICE BETWEENthou

AND

you

In Old English,

thou

(

thee, thine

, etc.) was singular and

you

was plural. But during the thirteenth century,

you

started to be used as a polite form of the singular - probably because people copied the French way of talking, where vous was used in that way. English then became like French, which has tu and vous both possible for singulars; and that allowed a choice. The norm was for

you

to be used by inferiors to superiors - such as children to parents, or servants to masters, and thou would be used in return. But

thou

was also used to express special intimacy, such as when addressing God. It was also used when the lower classes talked to each other. The upper classes used

you

to each other, as a rule, even when they were closely related.

thou

(

thee, thine

, etc.) was singular and

you

was plural. But during the thirteenth century,

you

started to be used as a polite form of the singular - probably because people copied the French way of talking, where vous was used in that way. English then became like French, which has tu and vous both possible for singulars; and that allowed a choice. The norm was for

you

to be used by inferiors to superiors - such as children to parents, or servants to masters, and thou would be used in return. But

thou

was also used to express special intimacy, such as when addressing God. It was also used when the lower classes talked to each other. The upper classes used

you

to each other, as a rule, even when they were closely related.

So, when someone changes from

thou

to you in a conversation, or the other way round, it conveys a different pragmatic force. It will express a change of attitude, or a new emotion or mood. As an illustration, we can observe the switching of pronouns as an index of Regan’s state of mind when she tries to persuade Oswald to let her see Goneril’s letter (

The Tragedy of King Lear

, 4.4.119-40). She begins with the expected

you

, but switches to thee when she tries to use her charm:

thou

to you in a conversation, or the other way round, it conveys a different pragmatic force. It will express a change of attitude, or a new emotion or mood. As an illustration, we can observe the switching of pronouns as an index of Regan’s state of mind when she tries to persuade Oswald to let her see Goneril’s letter (

The Tragedy of King Lear

, 4.4.119-40). She begins with the expected

you

, but switches to thee when she tries to use her charm:

REGANWhy should she write to Edmond? Might not you

Transport her purposes by word? Belike—

Some things—I know not what. I’ll love thee much:

Let me unseal the letter.OSWALDMadam, I had rather—REGANI know your lady does not love her husband.

Oswald’s hesitation makes her return to

you

again, and she soon dismisses him in an abrupt short line with this pronoun; but when he responds enthusiastically to her next request she opts again for

thee

:

you

again, and she soon dismisses him in an abrupt short line with this pronoun; but when he responds enthusiastically to her next request she opts again for

thee

:

I pray desire her call her wisdom to her.

So, fare you well.

If you do chance to hear of that blind traitor,

Preferment falls on him that cuts him off.OSWALDWould I could meet him, madam. I should show

What party I do follow.REGANFare thee well.

Other books

Endgame (Voluntary Eradicators) by Campbell, Nenia

La biblia de los caidos by Fernando Trujillo

Stars in Jars by Chrissie Gittins

The Drowning Game by LS Hawker

The Warlords Revenge by Alyssa Morgan

Lingerie and Lariats (Rough & Ready#7) by Cheyenne McCray

Take Me As I Am by JM Dragon, Erin O'Reilly

The Dead Man by Joel Goldman

The Naughty Sins Of A Saint by Tiana Laveen