William Shakespeare: The Complete Works 2nd Edition (190 page)

Read William Shakespeare: The Complete Works 2nd Edition Online

Authors: William Shakespeare

Tags: #Drama, #Literary Criticism, #Shakespeare

BOOK: William Shakespeare: The Complete Works 2nd Edition

12.76Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

CHIEF WATCHMAN

Here is a friar, and slaughtered Romeo’s man,

With instruments upon them fit to open

These dead men’s tombs.

With instruments upon them fit to open

These dead men’s tombs.

CAPULET

O heavens! O wife, look how our daughter bleeds!

This dagger hath mista’en, for lo, his house

Is empty on the back of Montague,

And it mis-sheathèd in my daughter’s bosom.

This dagger hath mista’en, for lo, his house

Is empty on the back of Montague,

And it mis-sheathèd in my daughter’s bosom.

CAPULET’S WIFE

O me, this sight of death is as a bell 205

That warns my old age to a sepulchre.

That warns my old age to a sepulchre.

Enter Montague

PRINCE

Come, Montague, for thou art early up

To see thy son and heir more early down.

To see thy son and heir more early down.

MONTAGUE

Alas, my liege, my wife is dead tonight.

Grief of my son’s exile hath stopped her breath. 210

What further woe conspires against mine age?

Grief of my son’s exile hath stopped her breath. 210

What further woe conspires against mine age?

PRINCE Look, and thou shalt see.

MONTAGUE (seeing Romeo’s body)

O thou untaught! What manners is in this,

To press before thy father to a grave?

To press before thy father to a grave?

PRINCE

Seal up the mouth of outrage for a while, 215

Till we can clear these ambiguities

And know their spring, their head, their true descent;

And then will I be general of your woes,

And lead you even to death. Meantime, forbear,

And let mischance be slave to patience. 220

Bring forth the parties of suspicion.

Till we can clear these ambiguities

And know their spring, their head, their true descent;

And then will I be general of your woes,

And lead you even to death. Meantime, forbear,

And let mischance be slave to patience. 220

Bring forth the parties of suspicion.

FRIAR LAURENCE

I am the greatest, able to do least,

Yet most suspected, as the time and place

Doth make against me, of this direful murder;

And here I stand, both to impeach and purge

Myself condemned and myself excused.

Yet most suspected, as the time and place

Doth make against me, of this direful murder;

And here I stand, both to impeach and purge

Myself condemned and myself excused.

PRINCE

Then say at once what thou dost know in this.

FRIAR LAURENCE

I will be brief, for my short date of breath

Is not so long as is a tedious tale.

Romeo, there dead, was husband to that Juliet,

And she, there dead, that Romeo’s faithful wife.

I married them, and their stol’n marriage day

Was Tybalt’s doomsday, whose untimely death

Banished the new-made bridegroom from this city,

For whom, and not for Tybalt, Juliet pined.

You, to remove that siege of grief from her,

Betrothed and would have married her perforce

To County Paris. Then comes she to me,

And with wild looks bid me devise some mean

To rid her from this second marriage,

Or in my cell there would she kill herself.

Then gave I her—so tutored by my art—

A sleeping potion, which so took effect

As I intended, for it wrought on her

The form of death. Meantime I writ to Romeo

That he should hither come as this dire night

To help to take her from her borrowed grave,

Being the time the potion’s force should cease.

But he which bore my letter, Friar John,

Was stayed by accident, and yesternight 250

Returned my letter back. Then all alone,

At the prefixèd hour of her waking,

Came I to take her from her kindred’s vault,

Meaning to keep her closely at my cell

Till I conveniently could send to Romeo.

But when I came, some minute ere the time

Of her awakening, here untimely lay

The noble Paris and true Romeo dead.

She wakes, and I entreated her come forth

And bear this work of heaven with patience. 260

But then a noise did scare me from the tomb,

And she, too desperate, would not go with me,

But, as it seems, did violence on herself.

All this I know, and to the marriage

Her nurse is privy; and if aught in this

Miscarried by my fault, let my old life

Be sacrificed, some hour before his time,

Unto the rigour of severest law.

Is not so long as is a tedious tale.

Romeo, there dead, was husband to that Juliet,

And she, there dead, that Romeo’s faithful wife.

I married them, and their stol’n marriage day

Was Tybalt’s doomsday, whose untimely death

Banished the new-made bridegroom from this city,

For whom, and not for Tybalt, Juliet pined.

You, to remove that siege of grief from her,

Betrothed and would have married her perforce

To County Paris. Then comes she to me,

And with wild looks bid me devise some mean

To rid her from this second marriage,

Or in my cell there would she kill herself.

Then gave I her—so tutored by my art—

A sleeping potion, which so took effect

As I intended, for it wrought on her

The form of death. Meantime I writ to Romeo

That he should hither come as this dire night

To help to take her from her borrowed grave,

Being the time the potion’s force should cease.

But he which bore my letter, Friar John,

Was stayed by accident, and yesternight 250

Returned my letter back. Then all alone,

At the prefixèd hour of her waking,

Came I to take her from her kindred’s vault,

Meaning to keep her closely at my cell

Till I conveniently could send to Romeo.

But when I came, some minute ere the time

Of her awakening, here untimely lay

The noble Paris and true Romeo dead.

She wakes, and I entreated her come forth

And bear this work of heaven with patience. 260

But then a noise did scare me from the tomb,

And she, too desperate, would not go with me,

But, as it seems, did violence on herself.

All this I know, and to the marriage

Her nurse is privy; and if aught in this

Miscarried by my fault, let my old life

Be sacrificed, some hour before his time,

Unto the rigour of severest law.

PRINCE

We still have known thee for a holy man.

Where’s Romeo’s man? What can he say to this? 270

Where’s Romeo’s man? What can he say to this? 270

BALTHASAR

I brought my master news of Juliet’s death,

And then in post he came from Mantua

To this same place, to this same monument.

This letter he early bid me give his father,

And threatened me with death, going in the vault,

If I departed not and left him there.

And then in post he came from Mantua

To this same place, to this same monument.

This letter he early bid me give his father,

And threatened me with death, going in the vault,

If I departed not and left him there.

PRINCE

Give me the letter. I will look on it.

Where is the County’s page that raised the watch?

Sirrah, what made your master in this place?

He takes the letter

Sirrah, what made your master in this place?

PAGE

He came with flowers to strew his lady’s grave,

And bid me stand aloof, and so I did.

Anon comes one with light to ope the tomb,

And by and by my master drew on him,

And then I ran away to call the watch.

And bid me stand aloof, and so I did.

Anon comes one with light to ope the tomb,

And by and by my master drew on him,

And then I ran away to call the watch.

PRINCE

This letter doth make good the friar’s words,

Their course of love, the tidings of her death;

And here he writes that he did buy a poison

Of a poor ’pothecary, and therewithal

Came to this vault to die, and lie with Juliet.

Where be these enemies? Capulet, Montague, 290

See what a scourge is laid upon your hate,

That heaven finds means to kill your joys with love.

And I, for winking at your discords, too

Have lost a brace of kinsmen. All are punished.

Their course of love, the tidings of her death;

And here he writes that he did buy a poison

Of a poor ’pothecary, and therewithal

Came to this vault to die, and lie with Juliet.

Where be these enemies? Capulet, Montague, 290

See what a scourge is laid upon your hate,

That heaven finds means to kill your joys with love.

And I, for winking at your discords, too

Have lost a brace of kinsmen. All are punished.

CAPULET

O brother Montague, give me thy hand. 295

This is my daughter’s jointure, for no more

Can I demand.

This is my daughter’s jointure, for no more

Can I demand.

MONTAGUE But I can give thee more,

For I will raise her statue in pure gold,

That whiles Verona by that name is known

There shall no figure at such rate be set 300

As that of true and faithful Juliet.

That whiles Verona by that name is known

There shall no figure at such rate be set 300

As that of true and faithful Juliet.

CAPULET

As rich shall Romeo’s by his lady’s lie,

Poor sacrifices of our enmity.

Poor sacrifices of our enmity.

PRINCE

A glooming peace this morning with it brings.

The sun for sorrow will not show his head. 305

Go hence, to have more talk of these sad things.

Some shall be pardoned, and some punishèd;

For never was a story of more woe

Than this of Juliet and her Romeo.

The sun for sorrow will not show his head. 305

Go hence, to have more talk of these sad things.

Some shall be pardoned, and some punishèd;

For never was a story of more woe

Than this of Juliet and her Romeo.

⌈

The tomb is closed.

⌉

Exeunt

A MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM

FRANCIS MERES mentions

A Midsummer Night’s Dream

in his

Palladis Tamia,

of 1598, and it was first printed in 1600. The Folio (1623) version offers significant variations apparently deriving from performance, and is followed in the present edition. It has often been thought that Shakespeare wrote the play for an aristocratic wedding, but there is no evidence to support this speculation, and the 1600 title-page states that it had been ’sundry times publicly acted’ by the Lord Chamberlain’s Men. In stylistic variation it resembles Love’s Labour’s Lost: both plays employ a wide variety of verse measures and rhyme schemes, along with prose that is sometimes (as in Bottom’s account of his dream, 4.1.202―15) rhetorically patterned. Probably it was written in 1594 or 1595, either just before or just after Romeo and Juliet.

A Midsummer Night’s Dream

in his

Palladis Tamia,

of 1598, and it was first printed in 1600. The Folio (1623) version offers significant variations apparently deriving from performance, and is followed in the present edition. It has often been thought that Shakespeare wrote the play for an aristocratic wedding, but there is no evidence to support this speculation, and the 1600 title-page states that it had been ’sundry times publicly acted’ by the Lord Chamberlain’s Men. In stylistic variation it resembles Love’s Labour’s Lost: both plays employ a wide variety of verse measures and rhyme schemes, along with prose that is sometimes (as in Bottom’s account of his dream, 4.1.202―15) rhetorically patterned. Probably it was written in 1594 or 1595, either just before or just after Romeo and Juliet.

Shakespeare built his own plot from diverse elements of literature, drama, legend, and folklore, supplemented by his imagination and observation. There are four main strands. One, which forms the basis of the action, shows the preparations for the marriage of Theseus, Duke of Athens, to Hippolyta, Queen of the Amazons, and (in the last act) its celebration. This is indebted to Chaucer’s

Knight’s Tale

, as is the play’s second strand, the love story of Lysander and Hermia (who elope to escape her father’s opposition) and of Demetrius. In Chaucer, two young men fall in love with the same girl and quarrel over her; Shakespeare adds the comic complication of another girl (Helena) jilted by, but still loving, one of the young men. A third strand shows the efforts of a group of Athenian workmen—the ‘mechanicals’—led by Bottom the Weaver to prepare a play, Pyramus and Thisbe (based mainly on Arthur Golding’s translation of Ovid’s Metamorphoses) for performance at the Duke’s wedding. The mechanicals themselves belong rather to Elizabethan England than to ancient Greece. Bottom’s partial transformation into an ass has many literary precedents. Fourthly, Shakespeare depicts a quarrel between Oberon and Titania, King and Queen of the Fairies. Oberon’s attendant, Robin Goodfellow, a puck (or pixie), interferes mischievously in the workmen’s rehearsals and the affairs of the lovers. The fairy part of the play owes something to both folklore and literature; Robin Goodfellow was a well-known figure about whom Shakespeare could have read in Reginald Scot’s Discovery of Witchcraft (1586).

Knight’s Tale

, as is the play’s second strand, the love story of Lysander and Hermia (who elope to escape her father’s opposition) and of Demetrius. In Chaucer, two young men fall in love with the same girl and quarrel over her; Shakespeare adds the comic complication of another girl (Helena) jilted by, but still loving, one of the young men. A third strand shows the efforts of a group of Athenian workmen—the ‘mechanicals’—led by Bottom the Weaver to prepare a play, Pyramus and Thisbe (based mainly on Arthur Golding’s translation of Ovid’s Metamorphoses) for performance at the Duke’s wedding. The mechanicals themselves belong rather to Elizabethan England than to ancient Greece. Bottom’s partial transformation into an ass has many literary precedents. Fourthly, Shakespeare depicts a quarrel between Oberon and Titania, King and Queen of the Fairies. Oberon’s attendant, Robin Goodfellow, a puck (or pixie), interferes mischievously in the workmen’s rehearsals and the affairs of the lovers. The fairy part of the play owes something to both folklore and literature; Robin Goodfellow was a well-known figure about whom Shakespeare could have read in Reginald Scot’s Discovery of Witchcraft (1586).

A Midsummer Night’s Dream offers a glorious celebration of the powers of the human imagination while also making comic capital out of its limitations. It is one of Shakespeare’s most polished achievements, a poetic drama of exquisite grace, wit, and humanity. In performance, its imaginative unity has sometimes been violated, but it has become one of Shakespeare’s most popular plays, with a special appeal for the young.

THE PERSONS OF THE PLAYTHESEUS, Duke of Athens

HIPPOLYTA, Queen of the Amazons, betrothed to Theseus

PHILOSTRATE, Master of the Revels to Theseus

EGEUS, father of Hermia

HERMIA, daughter of Egeus, in love with Lysander

LYSANDER, loved by Hermia

DEMETRIUS, suitor to Hermia

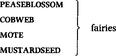

HELENA, in love with DemetriusOBERON, King of Fairies

TITANIA, Queen of Fairies

ROBIN GOODFELLOW, a puckPeter QUINCE, a carpenter

Nick BOTTOM, a weaver

Francis FLUTE, a bellows-mender

Tom SNOUT, a tinker

SNUG, a joiner

Robin STARVELING, a tailorAttendant lords and fairies

Enter Theseus, Hippolyta, and Philostrate, with others

THESEUS

Now, fair Hippolyta, our nuptial hour

Draws on apace. Four happy days bring in

Another moon—but O, methinks how slow

This old moon wanes! She lingers my desires

Like to a stepdame or a dowager

Long withering out a young man’s revenue.

Draws on apace. Four happy days bring in

Another moon—but O, methinks how slow

This old moon wanes! She lingers my desires

Like to a stepdame or a dowager

Long withering out a young man’s revenue.

HIPPOLYTA

Four days will quickly steep themselves in night,

Four nights will quickly dream away the time;

And then the moon, like to a silver bow

New bent in heaven, shall behold the night

Of our solemnities.

Four nights will quickly dream away the time;

And then the moon, like to a silver bow

New bent in heaven, shall behold the night

Of our solemnities.

THESEUS Go, Philostrate,

Stir up the Athenian youth to merriments.

Awake the pert and nimble spirit of mirth.

Turn melancholy forth to funerals—

The pale companion is not for our pomp.

Awake the pert and nimble spirit of mirth.

Turn melancholy forth to funerals—

The pale companion is not for our pomp.

⌈

Exit Philostrate

⌉

Hippolyta, I wooed thee with my sword,

And won thy love doing thee injuries.

But I will wed thee in another key—

With pomp, with triumph, and with revelling.

And won thy love doing thee injuries.

But I will wed thee in another key—

With pomp, with triumph, and with revelling.

Enter Egeus and his daughter Hermia, and Lysander and Demetrius

EGEUS

Happy be Theseus, our renowned Duke.

THESEUS

Thanks, good Egeus. What’s the news with thee?

EGEUS

Full of vexation come I, with complaint

Against my child, my daughter Hermia.—

Stand forth Demetrius.—My noble lord,

This man hath my consent to marry her.—

Stand forth Lysander.—And, my gracious Duke,

This hath bewitched the bosom of my child.

Thou, thou, Lysander, thou hast given her rhymes,

And interchanged love tokens with my child.

Thou hast by moonlight at her window sung

With feigning voice verses of feigning love,

And stol’n the impression of her fantasy

With bracelets of thy hair, rings, gauds, conceits,

Knacks, trifles, nosegays, sweetmeats—messengers

Of strong prevailment in unhardened youth. 35

With cunning hast thou filched my daughter’s heart,

Turned her obedience which is due to me

To stubborn harshness. And, my gracious Duke,

Be it so she will not here before your grace

Consent to marry with Demetrius,

I beg the ancient privilege of Athens:

As she is mine, I may dispose of her,

Which shall be either to this gentleman

Or to her death, according to our law

Immediately provided in that case.

Against my child, my daughter Hermia.—

Stand forth Demetrius.—My noble lord,

This man hath my consent to marry her.—

Stand forth Lysander.—And, my gracious Duke,

This hath bewitched the bosom of my child.

Thou, thou, Lysander, thou hast given her rhymes,

And interchanged love tokens with my child.

Thou hast by moonlight at her window sung

With feigning voice verses of feigning love,

And stol’n the impression of her fantasy

With bracelets of thy hair, rings, gauds, conceits,

Knacks, trifles, nosegays, sweetmeats—messengers

Of strong prevailment in unhardened youth. 35

With cunning hast thou filched my daughter’s heart,

Turned her obedience which is due to me

To stubborn harshness. And, my gracious Duke,

Be it so she will not here before your grace

Consent to marry with Demetrius,

I beg the ancient privilege of Athens:

As she is mine, I may dispose of her,

Which shall be either to this gentleman

Or to her death, according to our law

Immediately provided in that case.

THESEUS

What say you, Hermia? Be advised, fair maid.

To you your father should be as a god,

One that composed your beauties, yea, and one

To whom you are but as a form in wax,

By him imprinted, and within his power

To leave the figure or disfigure it.

Demetrius is a worthy gentleman.

To you your father should be as a god,

One that composed your beauties, yea, and one

To whom you are but as a form in wax,

By him imprinted, and within his power

To leave the figure or disfigure it.

Demetrius is a worthy gentleman.

Other books

Collection 1989 - Long Ride Home (v5.0) by Louis L'Amour

These Shallow Graves by Jennifer Donnelly

The Supernaturals by David L. Golemon

A Little Fate by Nora Roberts

All This Talk of Love by Christopher Castellani

Jack In The Green by Charles de Lint

Spellweaver by CJ Bridgeman

Blood Lines: Kallen's Tale (Witch Fairy #3.5) by Lamer, Bonnie

Seduced by Moonlight by Janice Sims

A Lord for Haughmond by K. C. Helms