William Shakespeare: The Complete Works 2nd Edition (5 page)

Read William Shakespeare: The Complete Works 2nd Edition Online

Authors: William Shakespeare

Tags: #Drama, #Literary Criticism, #Shakespeare

BOOK: William Shakespeare: The Complete Works 2nd Edition

13.01Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

There can be no doubt that the best actors of Shakespeare’s time would have been greatly admired in any age. English actors became famous abroad; some of the best surviving accounts are in letters written by visitors to England: the actors were literally ‘something to write home about’, and some of them performed (in English) on the Continent. Edward Alleyn, the leading tragedian of the Admiral’s Men, renowned especially for his performances of Marlowe’s heroes, made a fortune and founded Dulwich College. All too little is known about the actors of Shakespeare’s company and the roles they played, but many testimonies survive to Richard Burbage’s excellence in tragic roles. According to an elegy written after he died, in 1619,

No more young Hamlet, old Hieronimo;

Kind Lear, the grieved Moor, and more beside

That lived in him have now for ever died.

There is no reason to suppose that the boy actors lacked talent and skill; they were highly trained as apprentices to leading actors. Most plays of the period, including Shakespeare’s, have far fewer female than male roles, but some women’s parts—such as Rosalind (in

As You Like It

) and Cleopatra—are long and important; Shakespeare must have had confidence in the boys who played them. Some of them later became sharers themselves.

As You Like It

) and Cleopatra—are long and important; Shakespeare must have had confidence in the boys who played them. Some of them later became sharers themselves.

The playwriting techniques of Shakespeare and his contemporaries were intimately bound up with the theatrical conditions to which they catered. Theatre buildings were virtually confined to London. Plays continued to be given in improvised circumstances when the companies toured the provinces and when they acted at court (that is, wherever the sovereign and his or her entourage happened to be—in London, usually Whitehall or Greenwich). In 1602,

Twelfth Night

was given in the still-surviving hall of one of London’s Inns of Court, the Middle Temple. Acting companies could use guildhalls, the halls of great houses, the yards of inns, or even churches. (In 1608,

Richard II

and

Hamlet

were performed by ships’ crews at sea off the coast of Sierra Leone.) Many plays of the period require no more than an open space and the costumes and properties that the actors carried with them on their travels. Others made more use of the expanding facilities of the professional stage. No doubt texts were adapted as circumstances required.

Twelfth Night

was given in the still-surviving hall of one of London’s Inns of Court, the Middle Temple. Acting companies could use guildhalls, the halls of great houses, the yards of inns, or even churches. (In 1608,

Richard II

and

Hamlet

were performed by ships’ crews at sea off the coast of Sierra Leone.) Many plays of the period require no more than an open space and the costumes and properties that the actors carried with them on their travels. Others made more use of the expanding facilities of the professional stage. No doubt texts were adapted as circumstances required.

5. Richard Burbage: reputedly a self-portrait

6. The hall of the Middle Temple, London

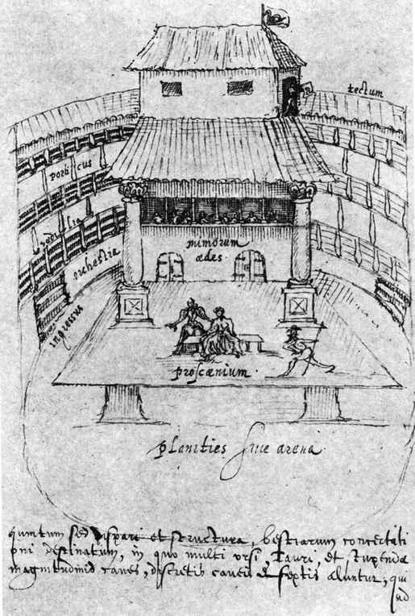

Permanent theatres were of two kinds, known now as public and private. Most important to Shakespeare were public theatres such as the Theatre, the Curtain, and the Globe. Unfortunately, the only surviving drawing (reproduced opposite) portraying the interior of a public theatre in any detail is of the Swan, not used by Shakespeare’s company. Though theatres were not uniform in design, they had important features in common. They were large wooden buildings, usually round or polygonal; the Globe, which was about 100 feet in diameter and 36 feet in height, could hold over three thousand spectators. Between the outer and inner walls—a space of about 12 feet—were three levels of tiered benches extending round most of the auditorium and roofed on top; after the Globe burnt down, in 1613, the roof, formerly thatched, was tiled. The surround of benches was broken on the lowest level by the stage, broad and deep, which jutted forth at a height of about 5 feet into the central yard, where spectators (‘groundlings’) could stand. Actors entered mainly, perhaps entirely, from openings in the wall at the back of the stage. At least two doors, one on each side, could be used; stage directions frequently call for characters to enter simultaneously from different doors, when the dramatic situation requires them to be meeting, and to leave ‘severally’ (separately) when they are parting. The depth of the stage meant that characters could enter through the stage doors some moments before other characters standing at the front of the stage might be expected to notice them.

Also in the wall at the rear of the stage there appears to have been some kind of central aperture which could be used for the disclosing and putting forth of Desdemona’s bed (

Othello

, 5.2) or the concealment of the spying Polonius

(Hamlet

, 3.4) or of the sleeping Lear (

The History of King Lear

, Sc. 20). Behind the stage wall was the tiring-house—the actors’ dressing area.

Othello

, 5.2) or the concealment of the spying Polonius

(Hamlet

, 3.4) or of the sleeping Lear (

The History of King Lear

, Sc. 20). Behind the stage wall was the tiring-house—the actors’ dressing area.

On the second level the seating facilities for spectators seem to have extended even to the back of the stage, forming a balcony which at the Globe was probably divided into five bays. Here perhaps was the ‘lords’ room’, which could be taken over by the actors for plays in which action took place ‘above’ (or ‘aloft’), as in Romeo’s wooing of Juliet or the death of Mark Antony in

Antony and Cleopatra

. It seems to have been possible for actors to move from the main stage to the upper level during the time taken to speak a few lines of verse, as we may see in

The Merchant of Venice

(2.6.51-8) or

Julius Caesar

(5.3.33-5). Somewhere above the lords’ room was a window or platform known as ‘the top’; Joan la Pucelle appears there briefly in I

Henry VI

(3.3), and in

The Tempest

, Prospero is seen ‘on the top, invisible’ (3.3).

Antony and Cleopatra

. It seems to have been possible for actors to move from the main stage to the upper level during the time taken to speak a few lines of verse, as we may see in

The Merchant of Venice

(2.6.51-8) or

Julius Caesar

(5.3.33-5). Somewhere above the lords’ room was a window or platform known as ‘the top’; Joan la Pucelle appears there briefly in I

Henry VI

(3.3), and in

The Tempest

, Prospero is seen ‘on the top, invisible’ (3.3).

Above the stage, at a level higher than the second gallery, was a canopy, probably supported by two pillars (which could themselves be used for concealment) rising from the stage. One function of the canopy was to shelter the stage from the weather; it also formed the floor of one or more huts housing the machinery for special effects and its operators. Here cannon-balls could be rolled around a trough to imitate the sound of thunder, and fire crackers could be set off to simulate lightning. And from this area actors could descend in a chair operated by a winch. Shakespeare uses this facility mainly in his late plays: in

Cymbeline

for the descent of Jupiter (5.5), and, probably, in

Pericles

for the descent of Diana (Sc. 21) and in

The Tempest

for Juno’s appearance in the masque (4.1). On the stage itself was a trap which could be opened to serve as Ophelia’s grave (

Hamlet

, 5.1) or as Malvolio’s dungeon (

Twelfth Night,

4.2).

Cymbeline

for the descent of Jupiter (5.5), and, probably, in

Pericles

for the descent of Diana (Sc. 21) and in

The Tempest

for Juno’s appearance in the masque (4.1). On the stage itself was a trap which could be opened to serve as Ophelia’s grave (

Hamlet

, 5.1) or as Malvolio’s dungeon (

Twelfth Night,

4.2).

7. The Swan Theatre: a copy, by Aernout van Buchel, of a drawing made about 1596 by Johannes de Witt, a Dutch visitor to London

Somewhere in the backstage area, perhaps in or close to the gallery, must have been a space for the musicians who played a prominent part in many performances. No doubt then, as now, a single musician was capable of playing several instruments. Stringed instruments, plucked (such as the lute) and bowed (such as viols), were needed. Woodwind instruments included recorders (called for in

Hamlet

, 3.2) and the stronger, shriller hautboys (ancestors of the modern oboe); trumpets and cornetts were needed for the many flourishes and sennets (more elaborate fanfares) played especially for the comings and goings of royal characters. Sometimes musicians would play on stage: entrances for trumpeters and drummers are common in battle scenes. More often they would be heard but not seen; from behind the stage (as, perhaps, at the opening of

Twelfth Night

or in the concluding dance of Much Ado About Nothing), or even occasionally under it (

Antony and Cleopatra

, 4.3). Some actors were themselves musicians: the performers of Feste (in

Twelfth Night)

and Ariel (in

The Tempest

) must sing and, probably, accompany themselves on lute and tabor (a small drum slung around the neck). Though traditional music has survived for some of the songs in Shakespeare’s plays (such as Ophelia’s mad songs, in

Hamlet

), we have little music which was certainly composed for them in his own time. The principal exception is two songs for

The Tempest

by Robert Johnson, a fine composer who was attached to the King’s Men.

Hamlet

, 3.2) and the stronger, shriller hautboys (ancestors of the modern oboe); trumpets and cornetts were needed for the many flourishes and sennets (more elaborate fanfares) played especially for the comings and goings of royal characters. Sometimes musicians would play on stage: entrances for trumpeters and drummers are common in battle scenes. More often they would be heard but not seen; from behind the stage (as, perhaps, at the opening of

Twelfth Night

or in the concluding dance of Much Ado About Nothing), or even occasionally under it (

Antony and Cleopatra

, 4.3). Some actors were themselves musicians: the performers of Feste (in

Twelfth Night)

and Ariel (in

The Tempest

) must sing and, probably, accompany themselves on lute and tabor (a small drum slung around the neck). Though traditional music has survived for some of the songs in Shakespeare’s plays (such as Ophelia’s mad songs, in

Hamlet

), we have little music which was certainly composed for them in his own time. The principal exception is two songs for

The Tempest

by Robert Johnson, a fine composer who was attached to the King’s Men.

Shakespeare’s plays require few substantial properties. A ‘state’, or throne on a dais, is sometimes called for, as are tables and chairs and, occasionally, a bed, a pair of stocks

(King Lear

, Sc.

7/2.2

), a cauldron (

Macbeth,

4.1), a rose brier (

I Henry VI,

2.4), and a bush (

Two Noble Kinsmen

, 5.3). No doubt these and other such objects were pushed on and off the stage by attendants in full view of the audience. We know that Elizabethan companies spent lavishly on costumes, and some plays require special clothes; at the beginning of 2

Henry IV

, Rumour enters ‘painted full of tongues’; regal personages, and supernatural figures such as Hymen in As You Like It (5.4) and the goddesses in

The Tempest

(4.1), must have been distinctively costumed; presumably a bear-skin was needed for

The Winter’s Tale

(3.3). Probably no serious attempt was made at historical realism. The only surviving contemporary drawing of a scene from a Shakespeare play, illustrating

Titus Andronicus

(reproduced on the following page), shows the characters dressed in a mixture of Elizabethan and classical costumes, and this accords with the often anachronistic references to clothing in plays with a historical setting. The same drawing also illustrates the use of head-dresses, of varied weapons as properties—the guard to the left appears to be wearing a scimitar—of facial and bodily make-up for Aaron, the Moor, and of eloquent gestures. Extended passages of wordless action are not uncommon in Shakespeare. Dumb shows feature prominently in earlier Elizabethan plays, and in Shakespeare the direction ‘alarum’ or ‘alarums and excursions’ may stand for lengthy and exciting passages of arms. Even in one of Shakespeare’s latest plays,

Cymbeline,

important episodes are conducted in wordless mime (see, for example, 5.2-4).

(King Lear

, Sc.

7/2.2

), a cauldron (

Macbeth,

4.1), a rose brier (

I Henry VI,

2.4), and a bush (

Two Noble Kinsmen

, 5.3). No doubt these and other such objects were pushed on and off the stage by attendants in full view of the audience. We know that Elizabethan companies spent lavishly on costumes, and some plays require special clothes; at the beginning of 2

Henry IV

, Rumour enters ‘painted full of tongues’; regal personages, and supernatural figures such as Hymen in As You Like It (5.4) and the goddesses in

The Tempest

(4.1), must have been distinctively costumed; presumably a bear-skin was needed for

The Winter’s Tale

(3.3). Probably no serious attempt was made at historical realism. The only surviving contemporary drawing of a scene from a Shakespeare play, illustrating

Titus Andronicus

(reproduced on the following page), shows the characters dressed in a mixture of Elizabethan and classical costumes, and this accords with the often anachronistic references to clothing in plays with a historical setting. The same drawing also illustrates the use of head-dresses, of varied weapons as properties—the guard to the left appears to be wearing a scimitar—of facial and bodily make-up for Aaron, the Moor, and of eloquent gestures. Extended passages of wordless action are not uncommon in Shakespeare. Dumb shows feature prominently in earlier Elizabethan plays, and in Shakespeare the direction ‘alarum’ or ‘alarums and excursions’ may stand for lengthy and exciting passages of arms. Even in one of Shakespeare’s latest plays,

Cymbeline,

important episodes are conducted in wordless mime (see, for example, 5.2-4).

Towards the end of Shakespeare’s career his company regularly performed in a private theatre, the Blackfriars, as well as at the Globe. Like other private theatres, this was an enclosed building, using artificial lighting, and so more suitable for winter performances. Private playhouses were smaller than the public ones—the Blackfriars held about 600 spectators—and admission prices were much higher—a minimum of sixpence at the Blackfriars against one penny at the Globe. Facilities at the Blackfriars must have been essentially similar to those at the Globe since some of the same plays were given at both theatres. But the sense of social occasion seems to have been different. Audiences were more elegant (though not necessarily better behaved); music featured more prominently.

8. A drawing, attributed to Henry Peacham, illustrating Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus

Other books

Rohn Federbush - Sally Bianco 01 - The Legitimate Way by Rohn Federbush

Chronicles of Kin Roland 1: Enemy of Man by Scott E Moon

Possession by Tori Carrington

1 State of Grace by John Phythyon

To Have and to Hold (Cactus Creek Cowboys) by Greenwood, Leigh

Hunger (Chicken Ranch Gentlemen's Club Book 1) by Amanda Young

AnchorandStorm by Kate Poole

The Alchemy of Murder by Carol McCleary

Who's Sorry Now (2008) by Lightfoot, Freda

Some Like it Scottish by Patience Griffin