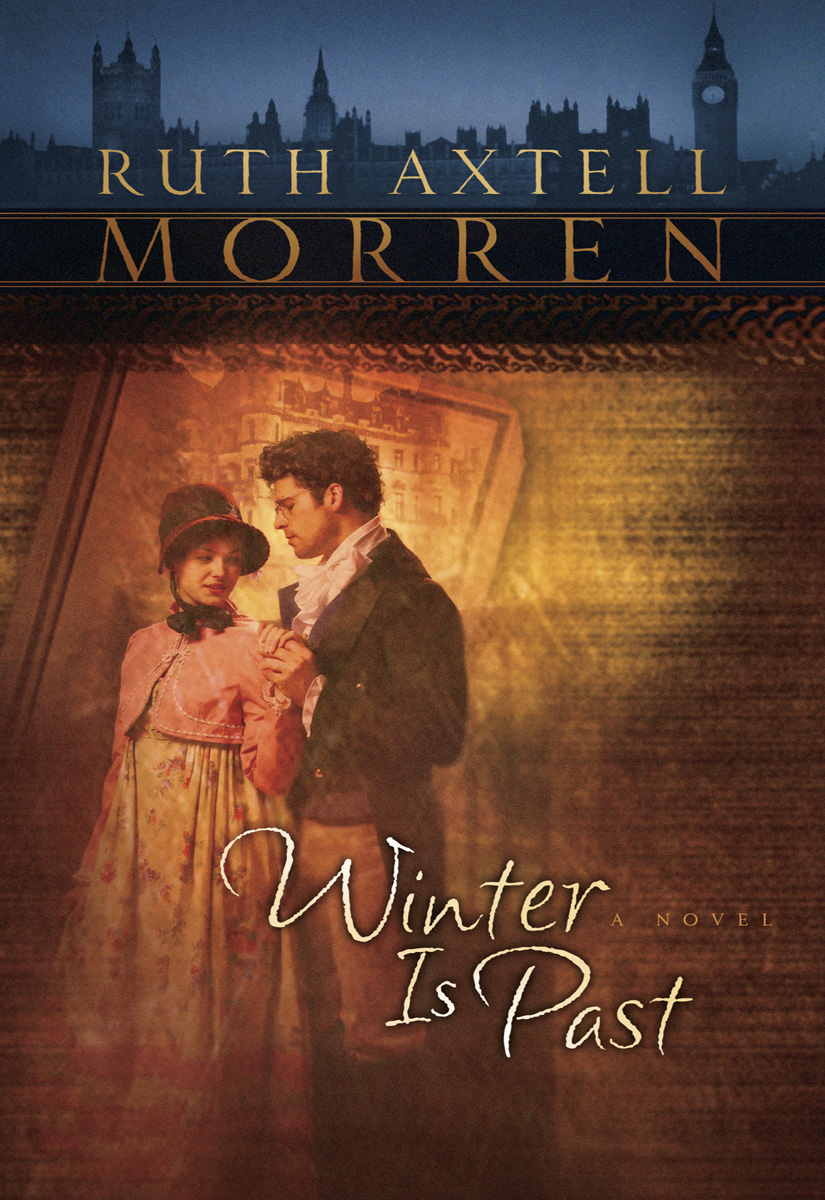

Winter Is Past

Authors: Ruth Axtell Morren

Winter Is Past

I wish to dedicate this story to:

Yeshua ha Mashiach,

who taught me that little becomes much

in the master's hand;

To the Rebeccas I have known,

who went home early to be with Him;

And to Rick,

who has given me the opportunity to

study the male psyche up close over the years.

When a cousin of mine began investigating the possibilities of Jewish ancestry in our family's Colombian/Venezuelan roots, I suddenly became interested in the Sephardic branch of Judaism. Soon I was fascinated with the story of the expulsion of the Sephardic Jews from Spain in 1492.

In Spain, under the Inquisition, thousands of Jews were forced to convert to Catholicism. However, many of them continued to practice their religion clandestinely. When they were expelled from Spain and eventually migrated to Holland, the Middle East, England and the New World, they were more accustomed, perhaps, than Ashkenazi and other non-Sephardic Jews, to leading a “double life” between outward Christianity and inner Judaism.

During the early nineteenth century, when

Winter Is Past

takes place, Jews living in England were gaining greater acceptance in mainstream Christian society, though the old prejudices were still thriving. I've used this background in telling the story of Methodist nurse Althea Breton and her employer, Simon Aguilar, a Jew by birth who has for political reasons become a member of the Church of England. When Althea meets Simon for the first time, she faces her own ugly prejudices against Jews. At first afraid and unsure of what to expect from this “foreign man,” Althea realizes that she has believed half-truths, not God's true word regarding the Jewish people. Soon, through her faith and newly gained knowledge of Simon and his family, Althea comes to see that Jews, much

like Christians, are people of faith, family and love. Sadly, it took somewhat longer for England to officially acknowledge this.

The most famous story of an English

converso

is Benjamin Disraeli (1804â1881). He was a Sephardic Jew whose family migrated to England from Italy. Although his career in Parliament didn't begin until about a decade after Simon's, Disraeli, too, received baptism as an adolescent, attended a private school run by an independent minister and was elected to Parliament. Back then, only baptized members of Britain's official state church could receive higher education, wed legally or hold public office. Luckily, in 1858, a law was passed making it legal for Jews to be admitted as members of Parliament, paving the way for Disraeli as England's first and only Jewish prime minister.

For further reading on Sephardic Jewry, I highly recommend

The Cross and the Pear Tree: A Sephardic Journey

by Victor Perera.

London, 1817

“S

o you're the miracle worker.”

Althea stared back at the man addressing her across the wide mahogany desk, his eyes deep and dark and mocking. They held mystery and an ancestry centuries old. The small, wire-rimmed oval spectacles did nothing to diminish the force of the hooded brown irises fringed by thick lashes and framed by heavy, black brows.

“Lady Althea Pembroke,” he stated when she remained silent, the mockery edging his tone soft as the feathery quill he brushed against his fingertips.

“I am Althea Breton,” she answered the dark-haired man. When he continued looking at her from behind his desk, the sound of the feather against his skin magnified in the still room, she added, “Lord Skylar requested me to come.”

“Yes, he spoke to me of you.” The tone revealed nothing beyond the words. “But I believe he spoke to me of

Lady

Althea Pembroke. You are his sister, are you not?”

She removed her gaze from his, realizing the answer was not

a simple one. Why had Tertius compelled her into this interview, she asked herself for the hundredth time.

She took a deep breath, reining in her frustration like a woman gathering her skirts against the wind. “I am sorry for the confusion,” she managed to say at last. “I am Lord Skylar's

half

sister. Perhaps my brother did not have a chance to explain to you.”

He made a gesture of impatience with ink-stained fingers. They were long and pale, illuminated in the circle of light cast by the Argand lamp. “Well, Lady AltheaâMiss Bretonâwhatever name you choose to go by, the important thing is, do you know anything of nursing? Your brother seems to think so.”

Irritated by the insinuation she was operating under an alias, she compressed her lips to avoid any ill-advised reply. He didn't bother to await her answer, but looked back down at the papers he'd been studying when she'd been bidden to come in. So now she must speak to the crown of dark, disheveled curls, she thought, annoyed at his obvious inattention. It hadn't been her idea to come here, she wanted to tell him! She was here only as a favor to her brother, who'd practically begged her to hear his friend out. Now she was made to feel as if she were groveling for a position, when that was the last thing she was in need of. The last thing she desired. She was quite fine where she was, she wanted to clarify to those unruly locks.

As she looked at the bowed head and observed the rapid movements of the long, slim fingers, something inside her stirred, remembering her brother's stories. Had this man truly been unmercifully tormented at Eton by his fellow students, all because he was a Jew?

The word still gave her a shudder of revulsion as she pictured the greasy, black-garbed moneylenders in the East End. She tried to stifle it as she cleared her throat, deciding her best course was to get this uncomfortable interview over with. She spoke to the dark head. “If I can be of any help to your daughter, I would appreciate the opportunity to try.” Her tone emerged sounding calm and collected.

When he did not answer immediately, she studied what she

could see of his features. They certainly belied the image she had had. The Honorable Simon Aguilar looked younger than she'd pictured a man of thirty-two with four years in the House of Commons. He'd been the youngest member of Parliament elected since Pitt the Younger, which proved his brilliance and wit, according to Tertius, qualities which her brother had first witnessed in the schoolboy at Eton.

Her gaze traveled farther. He wasn't handsome, more like arresting, she judged. His cheeks were clean-shaven, with only a shadow of beard against the pale skin; the nose not the hooked beak she expected, but high-bridged and chiseled; the lips a cushion of crimson accentuating the pallor of his skin. His physiognomy denoted a man of study, not a rapacious swindler of the poor. If the dim, book-lined shelves on either side of the room were any indication, he rarely saw the light of day.

He looked up, catching her observation. He waved a hand to a seat in front of the desk, as if just then noticing that she still stood in front of it like a servant awaiting orders. “Please, my lady, have a seat.”

“

Miss

Breton,” she corrected quietly but firmly, determined to get that established from the outset, as she took the chair indicated.

“Very well,

Miss

Breton. Could you be so kind as to explain to me why someone of your rank should want to lower herself to a position of nurse?”

Althea looked at him, aware it would not be easy to explain. He had removed his spectacles. The dark, hooded eyes stared back at her, their skepticism telling her beforehand that he would not easily accept whatever she told him. “Nursing ought to be seen as the honorable and noble profession it is.”

His lips curved in a humorless smile. “Please spare me a eulogy on the glories of bathing a sick body and emptying its slop basin.”

She colored and bit back a retort. Leaning forward and placing both her hands against the massive desk, her eyes sought an entry through the curtain of contempt and disbelief confronting her. “Mr. Aguilar, if you will permit me.”

He raised a black eyebrow, looking like a falcon deciding the fate of its prey. She glanced down at her hands splayed against the polished wood, like a tiny sparrow's feet gripping the safety of a tree limb. She removed them and balled them in her lap, clearing her throat to give it more authority.

“My brother told me you were in need of a nurse for your childâa young girl, I believe.” The words sounded clipped to her earsâshe spoke in what the street urchins recognized as her “brooking no nonsense” tone.

At his curt nod, she continued. “I have some years' experience nursing the sick. I can assure you I am well able to care for your little girl.”

“You hardly look old enough to have spent several years in the sickroom.” He fingered his pen impatiently as he spoke, and she had the impression of hands never still.

“I am older than I look. My brother must have explained to youâ”

He let the pen go and waved the same hand in the air. “Yes, yes, Sky filled me in on your impeccable qualifications. Lady of rank, renouncing all her worldly position and goodsâincluding the honorific, I come to seeâto become a Dissenter, live among the poor and tend to the sick. I hope they are grateful.”

“I am not a Dissenter!” Realizing how sharp her voice sounded, she took a deep breath and began afresh. “

Methodist

is the correct term, if you must label me.”

She felt her cheeks burn and was annoyed with Tertius for having divulged her personal history, then quickly understood her brother must have been trying to convince his friend of her qualities for the positionâa position she was by no means convinced she should accept. She sat back and silently asked for grace to maintain her temper. Where was the fruit of patience she had cultivated for the past eight years?

“I only wish to help in any way I can,” she added more gently.

It was Simon Aguilar's turn to take his gaze away first, using the moment to remove a handkerchief from his pocket to polish his

spectacles. “Yes, well, there's not much anyone can do but make Rebecca as comfortable as possible and keep her entertained. Her original nurse left us last year when she chose the life of a baker's wife over that of nursemaid. I replaced her with a governess, who was with us up until about a month ago, when it grew too taxing for Rebecca to continue her lessons on a regular basis. That is not to say you can't teach her things or read to her when she wishes.” He replaced his spectacles as he ended the summation.

Althea nodded, digesting the information, determined to keep her mind on the reason she was there. “What exactly is wrong withâ¦Rebecca?”

He shrugged, toying instead with a brass seal on his desk. “The physicians each have a different opinion. But the truth is, none of them know.” He scowled. “Some say a brain fever, others a blood poisoning or liver ailment. She gets sick very often and tires easily.” Once again he fixed dark, brooding eyes on her. “The truth is, she is dying.”

In the stillness Althea heard only the faint sound of a late-winter rain outside the windows behind the desk, the steady drone impervious to the plight of the individual lives being played out within. She watched her future employer's long, pale fingers realign the papers before him into a stack. She realized with a start that she was already calling him her employer.

No, Lord!

she cried silently; she'd by no means accepted this as His path for her. Just as quickly, shame swept over her at her pettiness when a little girl's life was at stake.

“There's not a thing I or the best physicians in Londonâor youâcan do about my daughter's condition, but make Rebecca as happy and comfortable as possible until then. Do you understand? Do you think you can manage that? You won't have an attack of the vapors the first time you face a crisis with her?”

Althea drew in a breath, her pity evaporating. If he'd seen half of what she'd seen in her six years in the East End, he would know it took more than an ailing child to overset her nerves. After a few seconds she answered dryly, “No, sir.”

He dipped his pen into its inkstand. “I will pay you twelve pounds, fifteen shillings per quarter.” His attention switched back to the stack before him. He made a notation on the margin of the topmost sheet. “Does that suffice?”

He looked up and she nodded, caught unawares. She hadn't even considered remuneration when her brother had askedâpleaded withâher to come here.

“I feel strange offering such pitiable wages to a peeress.”

“I am

not

a peeress,” she stated, exasperation edging her tone. “I have no hereditary title.”

He looked back down, ignoring her comment. “One more thing. I am hiring you officially as âgoverness' to Rebecca, although unofficially you will be her nurse. I suspended her lessons, as I said.”

“But why the title of governess if I am to be her nurse?”

He replaced the pen in its stand. The long, almost bony, fingers pushed through the dark, thick curls, leaving them in more disarray than before. “Because, Miss Breton, as should be obvious to you, I would prefer my daughter not realize she is so sick as to need a nurse.”

Althea bit her lip at her obtuseness.

He continued in a slightly more civil tone. “Besides, it is not the norm to have a young lady of noble birth working in one's household as a nurse. Governess would seem to excite less curiosity. It has a certain veneer of respectability to it. A nurse usually hails from the lowest dregs of societyâ¦at least, that has been my experience up until recently,” he muttered, looking down at his papers once more.

He took up his pen, as something caught his eye on the page before him. He made another notation. Althea continued observing him, trying to reconcile his appearance and manner with the preconceptions she had of his people.

“What is it?”

She felt the blood rise in her cheeks, wishing for the first time in her life that she had more freckles to hide her heightened color. “N-nothing.”

“You find me interesting to look at?”

“Noâ¦not at all.”

“Does my Jewish heritage intrigue you?”

She started at his perception. After a few seconds she nodded.

“I expect your brother informed you of my conversion to the Church.” His lips curled sardonically. “But I imagine you, as most, assume it was only skin deepâ”

He rolled the pen between his fingers.

Her eyes were fixed on the motion.

“You are correct in your supposition that it was a conversion in name only. Indispensable, you understand, for my entry into Parliament.”

He plucked at the dark sleeve of his jacket. “The marks of generations of Jewry cannot be so easily effaced, can they? Once a Jew, always a Jewâisn't that what you think?” She stared at him, disconcerted by the frank admission of the purely materialistic rationale for his conversion.

“Tell me, my curiosity is piqued, did I meet all of your expectations? What did you come here expecting to see? An old man hunched over in a moldering coat, counting out his coin? Fangs, perhaps? A gross deformity? After all, we are the Jesus killers, are we not?”

He didn't give her an opportunity to answer. “Well, Miss Breton, I can assure you, you shall be perfectly safe under my roof. I have managed to control the baser instincts of my race under this semblance of the gentleman you see before you.” He leaned back in his chair, his dark gaze assessing her, making her feel as if she were the one at fault.

She found herself struggling to meet that gaze, which seemed to see beyond her pious garb and acts of mercy, to something deep within her of which even she was unaware. This was ridiculous, she told herself. She had nothing to reproach herself for; she had seen firsthand what those moneylenders had accomplished with their extortionary techniques.

Deciding she would merely ignore his words, just as he had so

many of her own, she asked, “What precisely are you looking for in a nurse?”

He looked at her as if trying to explain something to an imbecile. “Miss Breton, I am frequently not at home. I need someone I can trust with my child. I need someone to take care of her as if she were her own. I realize that may be difficult for a childless woman, much less a hired one, to comprehend, but nevertheless that is what I require. That is what Rebecca needs.” He sighed, raking a hand through his hair, a gesture Althea was coming to recognize as expressing his impatience with having to explain things to people of less astuteness or intelligence.

He gave her another assessing look. “I don't expect you to understand this. I only agreed to this interview because your brother spoke so glowingly of your abilities. Quite frankly, I must admit my doubt.”

“I see,” she said, bowing her head and looking down at her tightly clasped hands, their firmness belying her inner trembling. She did not know what she had expected from this interview, but certainly not the doubt, much less the downright hostility, in the man before her. All at once it occurred to her that she had come harboring those very same sentiments, yet had felt perfectly justified in holding them. The realization piqued her conscience. For a split second she experienced the clarity of God's spirit touching something within her. It was like a door opening upon an unused room, letting in a shaft of light. One could choose to shut the door, or allow it to open farther and flood the area. The latter way held an element of risk.