With Love and Quiches (4 page)

Read With Love and Quiches Online

Authors: Susan Axelrod

- Never forget presentation; garnish dishes in wine sauce with toasted buttered bread triangles. [Funny because sauce isn’t a garnish, and I would never use ordinary toasted buttered bread triangles.]

- Egg whites; the older the better—freeze in ice cube trays.

- Don’t use more than one rich sauce per meal. [This is achingly obvious!]

- Assemble all ingredients beforehand and measure accurately. [This one is good advice.]

- Onion—grip the onion, not the board. [What? I’m not even sure what I meant here.]

- Oil—must be room temperature for sauces. [How else?]

- Beurre Manie—knead 1 tbs. butter with 1 tbs. flour to thicken sauces. [A good basic technique, and simple to use for almost any sauce, sweet or savory.]

There were about twenty-five items on that list, and although many were right on, I don’t mind making fun of myself for the more misguided hints of my first foray into professional cooking.

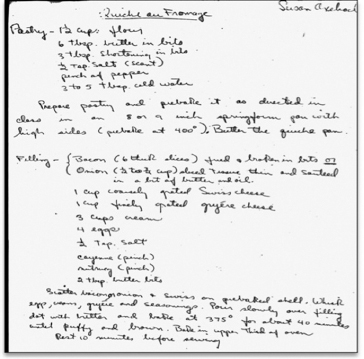

Also among the memorabilia I found while packing up our house was my original Quiche au Fromage recipe as it first appeared in my handouts for the ORT class. It doesn’t include the method for the crust (because I was demonstrating it), and the crust need

not

be pre-baked for sure. This quiche would, of course, become a staple of my business, and the product today has not changed all that much from the original. (Please note, though, that my instruction to bake in the upper third of the oven is dead wrong: the bottom third is better, giving you a browner bottom without burning the top.)

I found a lot more when packing up the house before our move to the city: I had been a compulsive recipe collector, and I had torn literally thousands of recipes out of magazines and other publications, recipes that I then saved for decades. I hadn’t looked at these recipes for many years, if ever, yet I had them spilling out of drawers, shopping bags, and cartons. I tossed them all, and it felt very good to do so. Cathartic to get rid of all that baggage! But all my notes and lesson plans for my cooking classes? And my cookbooks? They all came with me, even the overused and mildewed ones!

________

It’s hard to believe how unsophisticated I was when I taught those series of cooking courses. Many of the recipes and techniques I taught were taken from the elaborate dinners that I used to serve my friends, and teaching that material cost me a fortune in terms of both time and money: thirty to forty hours of preparation for each three-hour weekly session, and God only knew what I spent on all the foodstuffs I needed for each class, together with what I spent for other needed supplies, travel costs, and the additional hours in front of a copy machine preparing my giveaway materials for each participant. Yet I thought the $150 per session pay a princely sum—clueless as usual. It worked out to all of about ten cents per hour after my ingredient and supply expenses, but I had “tasted blood” for the first time and was ready to do something more important. The time to do something other than solely entertaining my friends had arrived.

Chance and serendipity are a recurring theme in my life, and the origins of my company are no exception. In junior high, I’d followed a friend to Woodmere Academy, a tony private school that at the time seemed far preferable to the public school in my neighborhood. One of my classmates there was a boy named Peter Davison, who I got to know but wasn’t particularly close with. After some time at Woodmere, I realized that I wasn’t the private school type, and I transferred back to Far Rockaway High School for my freshman year—which is a good thing, too, since that’s where I met Irwin.

Almost twenty years later, though, when we moved to Hewlett Harbor, I found out that Peter Davison’s sister lived in the neighborhood. I was looking to join a car pool for the children, so I called her up and told her I knew Peter. We found that our children had a few activities and interests in common and that we did too—primarily a

passion for food. Jill and I worked out a car pool and soon became good friends.

One day after Jill dropped Andrew and Joan off, she asked if I had a little time to talk. At the kitchen table, over coffee, we chatted about mundane topics of the day for a few minutes before Jill paused and asked me a question. “I’m thinking about starting some kind of business,” she said. “Something food related. Would you be interested?”

Well, as you can imagine,

that

gave me something to think about.

Getting Started (1973–1974)

There are times when you want a bull in a china shop.

—Somerset Maugham

O

nce I had processed what Jill asked me that day in the kitchen, my answer was immediate: “Yes.” I was game. Why

not

start a food-related business together? Jill was a great cook, and her mother had run a small but successful business selling Christmas decorations to the exclusive department store Henri Bendel, so Jill had always hoped to start a business of her own. To Jill, I seemed like a natural choice for a partner. I agreed.

Over the next few weeks, our planning commenced. Without giving it too much thought, we decided to call ourselves “Bonne Femme” (Good Lady). We thought it had a good ring to it, and we’d both always leaned toward the French style of cooking.

Our start-up was both very funny and bittersweet. It should be written in stone that no business, however small, should be started

without

some

kind of rudimentary business plan, but that’s exactly what we did. We had no idea what kind of food-related business we even wanted: Would we eventually run a small café? Sell food we’d cooked to restaurants? What kind of food should we sell? Instead of answering any of these basic questions, we just started taking step after step, somewhat blindly. We started with no business plan. We simply started.

The first step we took was a good one, at least: we contacted the New York State Department of Agriculture to have my house licensed as a “Bakery/Food Processing Plant.” Lots of people illegally sold food to restaurants from unlicensed home kitchens, but not me; I was brought up to always do the right thing. Somehow we got the license from the state, though I still have no idea how we managed to pull it off—for starters, my water heater surely wasn’t hot enough to qualify! I imagine we took them by surprise because not many people had asked before. Today, home kitchens are rarely, if ever, able to obtain such licenses, instead having to rent space in licensed commercial kitchens, but back in the early 1970s it must’ve been easier. We got a pass, and we still have the same plant number to this day.

So off we went, my partner and I, charging blindly forward. Now the next question: What to do? We started off with a stab at catering. By virtue of our culinary reputations, Jill and I were able to take on a half-dozen jobs in the neighborhood before we decided that catering was not for us. Neither Jill nor I liked walking in through the back door of events as hired help. (Little did I know that catering would have been a walk in the park compared to the path I’d take over the next few years—“Humble Pie” would become my middle name for a very long time.)

Now that catering was out, what next? I don’t remember exactly where the idea of quiche Lorraine came from, but once we happened upon it, it simply felt right. We looked at each other and said, “Let’s give

that

a try.” Our first quiche may have been an amateurish effort,

but I still consider it to be one of the best I have ever tasted. Without realizing it, I was marching into my destiny—and in that offhand manner, Bonne Femme was off to the races.

With a name, a license, and a product, all we had to do now was persuade somebody to buy our quiche. In our first attempt, we took a few samples to our local gourmet supermarket, the Windmill Food-store of Hewlett. As regular shoppers there, Jill and I both knew the owner. Our plan was to sell our quiche Lorraine to the store frozen raw, but we baked some off for the owner to sample. He ordered on the spot—our first sale, and it felt

very

good! Even better, he reordered, and then reordered again. Now we had our first repeat customer, and the journey had officially begun.

Our second regular customer followed soon after. I had the idea that we could make up some of the wonderful sauces I used for my dinner parties and sell them to the fish market just next door to the Windmill for use in their prepared foods section. I figured their customers would appreciate being able to pick up a delicious Newburg or cucumber-and-dill sauce with their purchase of fresh fish. The owner agreed, apparently, and soon Jill and I were cooking up and delivering the stuff by the gallon.

As owner-operators of Bonne Femme, we were truly clueless. We had no plan, no capital, kept our books in our heads, had no idea how to price our products, didn’t realize that our own labor was actually worth something, and operated in just my kitchen with equipment gathered from both of our homes. Despite our ignorance, at the end of a three-month period, we had ten or fifteen customers, all local. Most of our new customers were restaurants, and they were selling our quiches as fast as we could make them. The company had started to take shape.

Our days at Bonne Femme started at five in the morning, when Jill and I would have a phone call to plan the day. As soon as the kids left for school, Jill would come over and we’d get started—rolling dough, frying bacon, grating cheese, and all the rest. (I very often grated my

fingers along with the Swiss cheese, but even back then I had the sense to know I had to toss the cheese, not just pick through it to remove the bloody bits.) Everything was done by hand in tiny batches, and we were busy all day.

In the afternoon, I would run out to make deliveries while Jill, while doing her share, would typically pursue other interests. Somehow she still found time to run out for golf tournaments and things. After school, all of our children would get home, and we’d put them to work cracking eggs for the next day’s production. Things were beyond hectic, but I loved it.

With things up and running, Jill and I started asking questions of anyone who would listen. We got some good advice from a master baker who, with his father, owned and ran an old line European pastry shop two towns over. He taught us useful and practical things: for example, that water was a great binder, and free! He stored quiches for us as well and sold us pie pans at his cost.

I also had an old friend whose family owned a very successful local supermarket chain, and he offered to sell us ends and scraps of bacon in fifteen-pound packages really cheap! Prior to that we had been clearing local supermarket shelves of their most expensive bacon in very small packages. Of course this added to our labor and waste, but what did we know? Buying from my friend was a tiny step forward. He would even drop off the packets of ends and scraps for us on his way home from work. And we found ourselves buying quite a bit of it as we got more and more customers. I might add that frying all that bacon played havoc with my kitchen. It took years to finally clean out all the vents, which were almost completely blocked with the accumulated grease, and I am quite thankful that I didn’t burn my house down.

For all of our non-bacon ingredients, we were still raiding the local supermarkets and throwing off all their standard ordering patterns. We piled our grocery carts to the top with a hundred five-pound bags

of flour, and we’d clean out their shelves of Swiss, Gruyère, broccoli, spinach, and everything else we needed for our quiches. It fascinated the other shoppers and infuriated the management. The managers used to say, “Here they come again—hide everything!” So we had to keep changing supermarkets.

So far, we were still only selling frozen raw quiches, which we stored at my house, Jill’s house, and then all over the neighborhood. Then one of our customers, a local hamburger joint, asked if we could make them a pecan pie. That we could do! We had the pans, so why not? The dessert was a hit with the customers of that establishment, and our foray into desserts—our first line extension—was born. Soon we were also selling pecan pies to

all

of our restaurant customers.

The unbaked quiches needed to be frozen before we could pack them in plastic bags and stack them at our friends’ houses around town. We had come up with a system: we juxtaposed blocks from our children’s toy sets to add as many levels as possible in my laundry room freezer and the extra freezer in my garage, in order to freeze as many quiches at a time as we could. And by now we had

two

sizes: six inch for retail and nine inch for restaurants.

Once we started making desserts, we couldn’t exactly sell them frozen raw like our quiche (although we

tried

with the pecan pie), so we had to find a way to bake them efficiently. We came up with a similar system for baking desserts in our standard double ovens so that we could sneak in a few extra pies at a time. Nine per oven! Both of our houses! We started ferrying pails of pecan pie batter between houses. During one trip, a teenage hot-rodder came barreling out of a side street and slammed straight into my car, practically folding it in half and causing a veritable tsunami of batter all over the place. We repaired the car, but six months later the odor of very old butter

and eggs was still so strong that dozens of scrubbings couldn’t erase it; we gave up and got rid of the car.