Wobble to Death (7 page)

‘I was not with him to the end,’ Herriott answered. ‘We had two doctors in attendance, and they told me that the attacks were in the nature of muscular spasms. He was con-scious until the last moments.’

Cora covered her face, sobbing. Her father rested a hand on her arm.

‘The doctors,’ he said. ‘Could I see them?’

‘The doctor mainly concerned left to conduct the post-mortem examination at Islington mortuary. I shall be pleased to arrange a meeting later. The other doctor volun-teered his help. He is a competitor in the race—Mostyn-Smith. If you would care to meet him—’

‘Not if he is on the track at present. We should not inter-rupt his running again. Did either of the doctors venture an opinion of the cause?’

‘They said that tetanus was a possibility.’

‘Tetanus? You don’t get that running, do you? I thought it entered the body through a wound. Don’t soldiers get that? I’m sure it is due to dirty wounds.’

Herriott looked down.

‘I’m sorry. I know very little—’

‘But I really don’t understand,’ McCarthy persisted. ‘My son-in-law apparently died in agony from a disease that has to infect the body through a wound.’

‘His feet,’ faltered Herriott. ‘The blisters had broken. There were cuts. He ran on the path without boots or socks.’

Cora Darrell suddenly veered from passive grief to hys-terical anger.

‘Cuts! Open wounds! And he ran on them, over this filthy ground! What was his trainer doing, to allow this? Where is Sam Monk? What kind of trainer is he? Oh, Charlie, Charlie, he killed you. Monk killed you.’

McCarthy, mumbling apologies, tried to calm his daugh-ter. But she controlled herself, pushing him away.

‘I demand to see Mr Monk. I am entitled to a proper explanation. Where is my husband’s trainer?’

‘I . . . don’t think you should see him today,’ Herriott answered. ‘Like you, Mrs . . . Cora, he is in a distracted state. He could give you no proper answers.’

He remembered seeing Monk in the restaurant at lunch-time, drinking alone, and heavily. By now he would be in a stupor.

‘Mr Herriott is right, my dear,’ added McCarthy. ‘It would serve no useful purpose.’

Cora was now calm, and spoke slowly.

‘We shall sue that man, for wicked negligence. And you, Sol. We are old friends, I know, but if I can prove that you are responsible in any way for Charles’s death, I shall sue. You and your ridiculous race robbed me of his love—my lawful right—for the last six weeks of his life.’

‘Now, Cora,’ protested her father, ‘you cannot—’

‘There are thousands of witnesses to the filth of this building,’ she continued, ignoring him. ‘Thousands, Sol. And if the law allows it, I’ll prove you responsible.’

Herriott remained silent, stunned by the suddenness of the young widow’s attack. Cora had said all that she wanted and stood ready to leave. Her father formed an apology on his lips but only uttered a meaningless sound. Nodding awkwardly, he motioned Cora to the door and they left Herriott alone.

That evening was not a comfortable one for Herriott. Although a fair crowd accumulated in the stands they were less animated than the band. The performers on the track gave a dreary show. Only Billy Reid provided occasional diversions by sitting, on strike, at the track-edge, while his brother’s appeals were taken up by those near by, ‘Go it, Billy! You’ve got ’em all beat, my beauty. Get up, Billy boy!’—until he roused himself for another laborious circuit. Mid-way through the evening Sam Monk awoke from a drunken slumber in the restaurant and tottered into the arena pestering the officials for money. Herriott cast about for Jacobson, but the manager, as usual, was elsewhere, and the job of evicting Monk had to be his own.

Most of the audience had left and the pedestrians them-selves were starting to retire when Jacobson reappeared. With him were two strangers.

‘These gentlemen asked to meet you. They are from the police. Sergeant—er—’

‘Cribb—and Police Constable Thackeray. You are Mr Herriott, manager of this show?’

‘Promoter. Jacobson here is the manager.’

‘Very good. I am from the Detective Branch. Here to investigate the death of Charles Frederick Darrell. Pedestrian, I believe?’

‘Yes. But why—’

‘Doctors’ report came in tonight. He died of poisoning, sir. Enough strychnine in the corpse to put down a dray-horse. Where shall we talk?’

The Pedestrian Contest at Islington

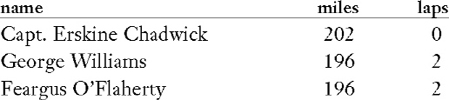

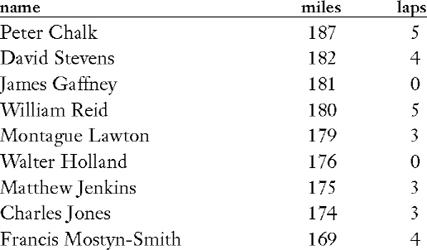

POSITIONS AT THE END OF THE SECOND DAY

C. Darrell (125 miles), and G. Stockwell (139 miles) retired from the race.

THE BOARDROOM STILL CONTAINED the bedstead which had been installed there eighteen hours earlier. It now served as a coat-rack. When he was seated, Herriott offered cigars to the other three, lit one for himself (he badly needed it), and studied the policemen, envying their vitality at this late hour. Sergeant Cribb remained standing, tall, spare in frame, too spry in his movements ever to put on much weight. His head, which switched positions with a birdlike suddenness, was burdened with an overlong nose. He had compensated for this by cultivating the bushiest Piccadilly Weepers that Herriott had seen. These, and his heavy eyebrows, were deep-brown, flecked with grey. He looked in his forties.

Jacobson asked, ‘What do you want us to do?’

‘Do, sir? Do nothing. Talk to us. That’s all.’

Cribb fastened his attention on Herriott.

‘The late Mr Darrell—tell me what you can about him.’

‘I can’t say that I knew very much about him at all, poor fellow. A first-class distance runner—I had that on expert advice, or I’d never have matched him with Chadwick. He trained uncommon hard for this race. Looked a cert when I watched him at Hackney Wick. His trainer was the best in England—Sam Monk.’

A nod to Constable Thackeray, who was busy with a notebook.

‘So you take him on. Give him any cash at this stage?’

‘That isn’t the practice. The prize money is generous enough. If Darrell won he would net five hundred, plus sidestakes.’

‘And if he didn’t?’

‘A hundred for second place. Fifty for third. The opposi-tion didn’t amount to much.’

Cribb paused, while his assistant, a burly, middle-aged man with a fine grey beard, caught up with his note-taking. ‘This newspaper.’ He produced a copy of that day’s

Star.

‘Read it?’

‘Some of it.’

‘The report on your affair?’

‘Yes. I read that.’

‘Substantially correct?’ asked Cribb.

The pace of his questioning was straining Herriott, who faltered. The question was flashed at Jacobson.

‘The details are right, yes. Some of the allusions to Mr Herriott—’

‘No matter. Darrell takes the lead after six hours. Right?’ ‘Yes.’

‘Chadwick falls behind, and takes to running?’

Jacobson nodded.

‘Not much resting till twenty-four hours are up?’

‘Only for light meals.’

‘Darrell’s wife—says here she visits him. He doesn’t stop?’

It seemed a very long time ago. Herriott took over the answers.

‘I showed Mrs Darrell around the arena. She didn’t want to interfere with the running.’

‘You show her around? She wants to see his tent, I expect?’

‘I simply introduced her to some of the officials. She knows most of us. We didn’t look into Darrell’s tent.’

Jacobson remembered. ‘Monk—that’s Darrell’s trainer— took Mrs Darrell in there.’

The eyebrows jerked higher. ‘For long?’

‘Oh, not much longer than five minutes.’

Constable Thackeray, finding the standing position awk-ward for writing, sat on the bed.

‘Then she leaves?’

‘As far as I can remember, yes.’

Cribb ran his finger down the newspaper which he was holding.

‘The last hour. Darrell in poor shape. Foxing, is he?’

‘Oh, I don’t think so,’ Jacobson answered. ‘His feet were troubling him. He took off his shoes before the end. Several of the runners were limping.’

‘Monk attends him, I suppose? Gets him back in the tent at one o’clock?’

‘Yes. Most of the competitors chose to rest at that stage.’ ‘Now then.’ Cribb had dissected the report to his satis-faction, and tossed the paper in Thackeray’s direction. ‘Darrell comes out again. What time?’

‘Soon after four.’

‘How’s he looking?’

‘Very good at that stage,’ Herriott recalled. ‘He set off at a clinking pace. The feet seemed to have improved a lot.’

‘Erratic?’

‘I don’t think so. He seemed well in command, but full of energy.’

Cribb’s face lit into a momentary smile.

‘Not surprising. Full of strychnine. Acts as a stimulant. The first spasm, now. When does that come?’

‘That would have been about six.’

‘Six. Is it now? Thought it might come earlier. Maybe the running makes a difference. Must check that.’

He patted the tip of his nose several times with his index finger.

‘Time of death? No matter. I’ve got that.’

Herriott took the opportunity of a lull in the interroga-tion to raise a point that was troubling him deeply.

‘Sergeant, this investigation. Does it mean that you will want me to cancel the race?’

‘Cancel? Whatever for? Keep it going, Mr Herriott. Keep it going as long as you can. Perfect for investigating a poisoning. Everyone’s here, you see. Might ask you to extend it into next week if I’m held up.’

Neither Jacobson nor Herriott was equal at this hour to the sergeant’s style of humour, so he turned to other matters.

‘This man Monk. He’s the cove I’ve got to see.’

‘You won’t learn much from him,’ commented Herriott. ‘The man is drunk. He took to the bottle this afternoon, drinking alone. He seemed to be doing it with the idea of get-ting stoned out of his mind. He fell into a stupor eventually, and then woke up and made a scene out there in the arena. I hauled him over to a spare hut. He’s sleeping it off there.’

‘We’ll have him out, then. Must grill him at once. Get him sobered up and bring him to Darrell’s tent. I’ll see him there.’

Herriott had hoped for a chance to sleep after the ques-tioning, but clearly he and Jacobson had been co-opted as members of the Detective Branch. Sergeant Cribb’s tone stifled protest.

‘Another thing,’ he snapped. ‘The second doctor, Mostyn-Smith. Hook him out of bed. We’ll hear his story while you dowse Monk.’

‘Mostyn-Smith won’t be in bed,’ said Jacobson. ‘He does-n’t normally rest for more than a half-hour. They say he gets his best walking done when the rest are sleeping. After this morning he’ll have a long stretch to make up.’

Cribb was not inconsiderate quite to the point of brutality. ‘Lost some ground did he? Can’t have him losing more, then. How long since you finished beat-bashing, Thackeray?’

The constable returned the look of a trapped bear.

‘Three years, Sarge. The feet, you know.’

‘Splendid. Should hold you up for a mile. Get out there with the Doc. You know the line of questioning. Not a word about the strychnine. We’ll keep that close at present. Understood, gents? Off you go, then.’

He passed each of the others his coat, and then tested the mattress of Darrell’s death-bed, heaved his long legs on to it and reclined there.

‘I’ll have that cigar before you go, Mr Herriott,’ he said.

THE GAS HAD been turned down soon after midnight, per-haps to encourage competitors to retire for their short sleep, and so release the late shift of officials. By one-fifteen, only Mostyn-Smith, his long-suffering lap-scorer and a somno-lent judge slumped in his chair occupied the arena. When the light in Chadwick’s tent was extinguished, the stunted blue flames on the chandeliers gave the scene a positively gloomy aspect. The little walker, at times hardly distinguish-able in his black costume, strode busily around the white-edged circuit, as though performing some gnomic ritual.

THE GAS HAD been turned down soon after midnight, per-haps to encourage competitors to retire for their short sleep, and so release the late shift of officials. By one-fifteen, only Mostyn-Smith, his long-suffering lap-scorer and a somno-lent judge slumped in his chair occupied the arena. When the light in Chadwick’s tent was extinguished, the stunted blue flames on the chandeliers gave the scene a positively gloomy aspect. The little walker, at times hardly distinguish-able in his black costume, strode busily around the white-edged circuit, as though performing some gnomic ritual.

Constable Edward Thackeray was not a man to be trou-bled by atmospheres, sinister or otherwise. His long career in the Force was blemished here and there by other short-comings, but in situations that required a steady pulse he was exemplary. It had become accepted in every station at which he served (he was often moved) that Thackeray was the constable who attended the most gruesome occasions; he was a tower of strength at exhumations. This gift unhap-pily did not bring the promotion that he once expected, but it had, early in 1878, brought him on to the fringe of a mur-der investigation, leading to the arrest of the notorious Charles Peace. The formation of the Detective Branch soon afterwards, and the call for constables experienced in serious crimes led to Thackeray’s present appointment. He was justly proud.

He approached the track and watched the solitary pedes-trian for a full lap, assessing the rate of progress as a cautious swimmer tests the water. At length he recognised Cribb’s brisk step somewhere behind him, and this encouraged him to cross the arena to await Mostyn-Smith on the track itself. He stepped smartly away at the right moment, pace for pace with the walker, exchanged identities and then gave all his attention to the walk. The rate of progress was not exces-sive, but he found that to maintain it comfortably he had to swing his arms across his chest. That, in ulster and bowler-hat, embarrassed him a little. Somewhere in the shadows Cribb would be savouring the spectacle.

At length, inhibitions conquered, he opened the ques-tioning.

‘You are the doctor who attended the man that died?’

‘I assisted. The official doctor was always in charge of the patient,’ answered Mostyn-Smith, speaking without strain.

‘You was with him till the end, though?’

‘Yes, that is true.’

‘What we need to know, Doctor, is whether he made statements of any sort while you attended him.’

There was a pause while they passed close to the lap-scorer.

‘Not strictly statements,’ Mostyn-Smith said. ‘The spasms were set off by the slightest movement, you see. Although he was fully conscious, we tried to discourage him from speech, even early in the condition. He did, however, make it clear, by the briefest utterances, that he could not understand the reason for his condition.’

‘What was they, sir?’

Thackeray instinctively felt for his notebook, thought again, and let it drop back into the pocket.

‘Oh, odd fragments. I remember that he said, “Never happened to me before.” And later, “What causes this?” Otherwise they were mostly exclamations of pain.’

The constable inhaled a gulp of air, committing the phrases to memory.

‘Did you give the man anything to drink?’

‘Warm tea, Officer. It sometimes helps.’

‘Nobody else visited the room I suppose?’

‘Nobody else.’

‘Thank you, sir. You didn’t know Mr Darrell before the race?’

‘Not at all.’

‘I think that’s all then, sir. You carrying on like this for long?’

‘Until Saturday. Good night to you.’

Thackeray eased his stride, and Mostyn-Smith padded cheerfully away into the gloom. The constable raised a leg and massaged his aching shin. At Cribb’s voice, immediately behind him, he dropped it like a guardsman.

‘Watch it, Thackeray. Next event the high jump.’

A bleak smile greeted the sergeant.

‘Right, then. What did you get while you were footing it?’ ‘Just as you thought, Sarge. Victim said very little, but enough to put suicide out of the question.’

They approached Darrell’s tent. Thackeray was moving forward to open the flap, when Cribb restrained him, rais-ing a hand for silence. With the stealth of a brave he crept to the opening, loosened the flap and flung it open. Someone inside scrambled to his feet. It was a uniformed policeman.

‘Never rest on duty,’ Cribb advised him. ‘I might have held a knife, lad.’

The young constable sheepishly emerged to face a with-ering look from Thackeray. Cribb dismissed him to the Hall’s police office where the detectives had first swooped on him as he was drinking cocoa, earlier in the evening.

With the lamp ignited, Darrell’s tent made a passable interviewing room. As well as two chairs and a bedside table, which Thackeray at once rearranged, there was a gas-ring and kettle. Milk and a teapot were found in a small food-cupboard, which also contained bread, whisky, a tin of liniment, various potions, a leathery remnant of calf-bladder and a slice of strong-smelling cod. Still on the table were the bottle and mug from which Darrell had taken Monk’s ‘bracer.’ Cribb sniffed at them charily and removed them to the cupboard.

‘We’ll have every liquid analysed,’ he announced. ‘Your job, Thackeray. Get ’em out at daybreak to a lab. Now where’s this trainer? Monk . . . Monk; heard of him, have you?’

‘Can’t say that I have, Sarge. But that don’t mean a lot. On my earnings I ain’t what you’d call one of the Fancy.’

‘Just as well,’ Cribb reassured him. ‘But if you ever do lay a bet, remember this: four legs support a body better than two. I’ll trade foot-racing for a Newmarket sweep any day.’ There was the sound outside of scuffled footsteps. Walter Jacobson entered, half-supporting Sam Monk, a bedraggled figure, damp about the head and shoulders. He deposited him in the waiting chair. He was about to seat himself on the still unmade bed when Cribb intervened.

‘My thanks, sir. And now you—and Mr Herriott’ (the promoter had just heralded his entry by kicking a hip bath) ‘shall get some sleep. Busy day coming up, I dare say.’

After their exit, Thackeray fastened the flap and took a standing position behind Monk, resting his weight on the chair-back. The flickering light greatly magnified his shadow so that it loomed over the trainer like a shade from hell. It was not his intention to terrorise the man. He was there merely to see that Monk did not relapse into sleep. The worst that threatened was a timely prod.