Writers of the Future, Volume 29 (35 page)

Read Writers of the Future, Volume 29 Online

Authors: L. Ron Hubbard

“Someone's got to keep this town safe,” Rey said, quietly.

“Yeah,” Mara said, looking up at him. “But it should be me. Keera's life

should be mine. She wasn't raised to this, like I was.”

“Keera does a fine job,” Rey said, shoulders stiff. “It ain't nobody's

fault what happened.”

“I know,” Mara said. “I know.”

Rey stepped forward and touched her shoulder gently, as if she might

spook. “Come on out of here. It's been a strange day, but it's done, yeah? Tomorrow

things'll look different.”

He winced as he thought over what he'd said but Mara laughed. “Maybe

they will,” she said. “What do I know?”

She hopped down off the rail and they left the horse in the barn for the

night with a little of the grain it'd carried on its back. The next day she'd have

to go to one of the neighbors, arrange to pick up some hay. It might be good, having

something living to care for.

They didn't talk as they left the barn and walked the bare-dirt path

that led back to their houses. When they came to the fork, where Rey would go on

straight and Mara would turn right, he hesitated as if he would say something, but

Mara cut him off with an easy smile. “Thanks for the help with the horse,” she said.

“Tell Keera I'll see her tomorrow out in the field.”

He nodded and they parted. The smile slipped from Mara's face as quickly

as it had come.

The shadows were long when she got to the front porch of her house, the

last of the sun gleaming through the scrubby trees. She stood a moment watching the

sun set, squinting into the light. And then she heard a scrabble of claws over her

roof, and the whirr of gears. A clockwork finch launched itself off the edge of her

house and into the air.

“What the hell're you doing here?” she said, her heart hammering.

The finch didn't answer. It flew in low loops overhead, crying the same

thing over and over in its shrill, rusty voice: “Well? Did you see it? Did you see

it? Did you see it?”

Mara watched the bird for a while, and then went inside and closed the

door.

T

wo weeks after the incident on

the river road, Mara woke early in the morning, lay still under her quilts, and

counted wood grains in the ceiling. As she counted, something in her gut relaxed,

something that awoke every morning tight and scared that this morning, she wouldn't

be able to count them.

Then she got up, dressed, and made herself some chicory. She looked out

the narrow kitchen window that faced the turnip field and wondered if Keera was

there already. She finished her chicory and rinsed the cup. Then she went to the

barn and tacked up the dead man's horse.

If the gray horse thought this strange, he made no mention, taking the

saddle and the bridle with the same quiet timidity he showed lipping carrots from

her hand. He was a good-natured horse, respectful and docile. The last horse they'd

taken from a dead harvester had been headstrong and young, a barely broke roan

gelding that they'd given to Rey. That one was still prone to little displays of

temper and meanness, with a wicked sideways spin. Not the sort of horse she would

choose to ride on a hunt, to be certain.

Mara tied the gray to a rail outside the barn and then stepped back

inside. In the empty stall where she kept the hay there were three trunks, each one

small and neat and locked. She took a silver key from the pocket of her coat and

fitted it to the lock on the first trunk. The lid opened easily, without a catch or

hesitation. The inside smelled of oil and metal. She pulled a wrapped bundle from

the trunk, about the length of her arm. She closed the trunk, locked it, and

returned to the horse.

She stepped into the stirrup and swung her leg over the gray's back. She

settled the wrapped bundle over the front of the saddle, balanced atop her thighs.

The horse shifted his weight uneasily but didn't move. She nudged him with her heel

and they set off at a swinging jog, away from her little house, away from the turnip

field.

On horseback, the trip out to the river road would take half the time it

had on foot. She didn't hurry, though, and let the gray set his own pace. His ears

twitched back and forth like bird's wings and she wondered if he remembered this

path. How at the end of it lay a slick of dried blood.

But the air was very fine, warm and still with nothing stirring but

insects,

click-click-click

ing in the grass. So she kept

a loose rein, her face turned up to the sun, and didn't think too much about what

she planned to do.

Most of the fields stood empty. She saw only one man out, paused over

his crops and leaning on his hoe. He hailed her and she stopped. He asked Mara if

she and her sister would attend the wedding in town, a few weeks away. She said they

would, though she hadn't talked to Keera about it.

When the path ran into the river road she turned right, the way they'd

gone to ambush the harvesters. She rode up to the place and stopped the horse but

there wasn't much trace left. All the blood had churned into dust and flaked away.

She got down and toed at the dirt with her boot. The horse stood by her shoulder and

snorted long bursts of breathâcatching some scent in the air, or maybe just

ghosts.

Mara returned to the vale where the bodies were hidden. Though some part

of her expected them to be gone, they were still there, lying in the razor grass.

Scavengers had been at them, and everything soft was eaten, leaving sunken holes in

their faces and their bellies and their throats. The smell of rot was strong enough

to make Mara's eyes water and her throat sting.

“What were you?” she asked the dead men. “Why did you come here?”

A black beetle crawled out the bottom of one man's jaw.

She turned and left the bodies where they lay and went back up to the

river road. She walked on foot with the horse beside her. When she reached a

clearing on the side of the road, with open space and big, mature trees, she stopped

and pulled down the long bundle she'd taken from the chest that morning. She

unwrapped it and let the cloth fall to the ground. The feeling of the wood and metal

under her fingers was just as familiar as she'd known it would be, as if she'd never

put it away.

She fussed with the rifle for a few minutes, making sure all the parts

were clean and working. Then she breathed in and raised it to her shoulder. There

was a tree with a big burl in the center, like a target, and she squinted one eye

shut to aim.

She breathed out, and fired.

Much later she sat on the grass in the clearing with the rifle leaning

against her shoulder and looked up at the spattering of shot deep in the burl. She

couldn't put a shot just where she wanted it anymore.

“Missed you in the field this morning,” Keera said behind her.

Mara leapt to her feet, the rifle in her hands. “Don't sneak up on me

like that.”

“Didn't think you were gonna shoot me,” Keera said, eyeing the gun.

“Did you walk all the way out here?”

“Yeah. I thought I might find you here.” For the first time, Mara

noticed the bag lying on the ground by her feet. Keera's rifle was there, too. “I've

got something I need to do,” Keera said. “Figured this was as good a time as

any.”

“What're you saying?”

Keera didn't answer. She stepped up next to her sister and looked over

at the trees, with their peppering of deep pits. “Looks pretty good. I didn't know

you were gonna take it up again.”

“It's been two weeks.” She didn't want to say it out loud, that she

might be able to see again, forever. Things like that couldn't be said, lest the

sound of them in the air prove them false. “I thought I'd try.”

“You don't need to,” Keera said. “Rey and I, we do all right. You don't

need to do anything if you don't want to.”

“I want to.”

“Why?” Keera asked, quietly.

“Because you shouldn't have to,” Mara said, sharp as a shot.

Keera flinched, her face shuttering. “It's my job now, by rights. You

can't change that just by shooting holes in a couple of trees.”

Mara looked down at her sister's hands, crooked into loose fists, tense

and steady. She remembered how they had shaken after Keera shot the man whose body

lay rotting in the razor grass. “I was meant to do it.”

“I know,” Keera said. “I know! But you got out of it, fair and square,

your damned

eyes,

and you can't come back now. I won't

let you.”

They stared across the dry ground, Keera tense and bright, a high flush

of color in her cheeks, Mara just tired. Tired with the weight trapped in her gut,

the weight of what she had done to her sister with her inability to do her damn job

right in the first place. “You hate it,” she said. “I know you do.”

“That doesn't matter.”

“It should.”

“But it doesn't,” Keera said. She stepped away from Mara and picked up

her rifle. “I'm going to go down the river road.”

“No,” Mara said. “What would you do that for? It's not safe.”

“I have to know where the harvesters come from, don't you see? And what

if there are other people out there fighting them? We could help each other.”

“There's not,” Mara said. “Nobody comes here, and nobody who leaves ever

comes back. That's how it's always been.”

“That doesn't mean it's law.” Keera turned and faced across the road,

over the broad expanse of the river. The sun sparkled off it, clean and beautiful.

“I've just got to know. Aboutâ”

She stopped. Mara finished for her: about those men lying there

dead.

“I thought you just told me you were going to do your job,” Mara said.

“Protecting the Goldwater.”

“And I am,” Keera snapped. “I'm doing it. I'm figuring it out, and then

I'm coming back.”

Mara didn't say anything.

“If you want to put those rifle skills to the test, you can help Rey

mind the place while I'm gone.” Keera bent, got her pack, and slung it over her

shoulder. “I'm sure he'd be glad for the help.”

“Does he know where you're going?”

“He knows I always try to do right by this town.” Keera's voice had lost

its edge. She sounded weary.

“All right.” Mara closed her eyes for a moment, let everything go black.

Would she have done the same in Keera's place?

“I came to ask if I could borrow that horse,” Keera said. “It'd make the

trip quicker. Ours is a spooky little devil so I won't take him.”

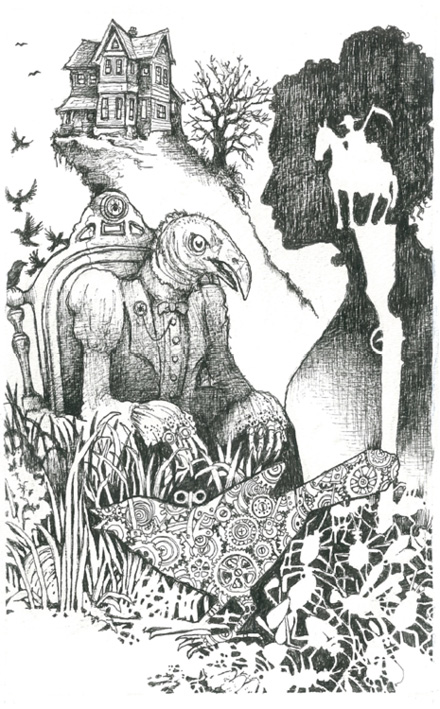

ILLUSTRATION BY JAMES J. EADS

“Take him. You can't go on foot.” She moved off to the horse, tied at

the edge of the clearing. On the way, she stopped next to her sister and softly

rapped their elbows together. “Come back soon.”

“I'll do my best.”

They packed Keera's things onto the gray in silence, and then Keera

swung into the saddle and stepped the horse back toward the road.

“I'll figure it out,” Keera said. “Who the harvesters are, where they're

coming from.”

“Be safe,” Mara said. “Shoot straight.”

Keera nodded and moved off down the road. Mara stood for a long time,

watching her sister and the horse grow small and indistinct in the distance. Then

she wrapped up her rifle and walked home, alone and on foot. Everything was quiet

except the sound of her footsteps on the packed dirt and the low burble of the

river. In the trees, one bird called and another one answered it.

A

wind swept through the Lady's

crooked house, licking through all the open windows and sending doors swinging,

open-shut-open. But the door to the Lady's parlor stayed closed. That door had never

been shut before when Mara came to visit. She stood frozen with her hand on the

knob, then leaned in close and put her ear to the wood. But she could hear nothing

inside. The Lady was very still, or she was gone.

Mara opened the door and stepped into the room.

The Lady came upon her in a rush of puckered bird skin and heavy green

velveteen and an open beak, hissing and snapping. The Lady slammed Mara back into

the doorframe, her hands digging hard into Mara's shoulders.

Mara choked and leaned her head back, despite herself. Her hands gripped

and relaxed but there was nothing to grab, no purchase on the smooth wood. Her rifle

at home and her knife still in her bootânot that she would dare use it on the Lady,

who had healed her. She steadied herself and gazed into the gap of the Lady's beak,

the wide black hole that led into her gullet. Mara thought,

Her

fingers are so strong. She's always looked frail, but she's not. She's

not.

“Why did you let her go?” the Lady hissed, her beak so close to Mara's

face, the sour blood stink of her breath gusting out.