Year of the Hyenas

Read Year of the Hyenas Online

Authors: Brad Geagley

Tags: #Fiction, #General, #Mystery & Detective, #Historical

A Novel of Murder in Ancient Egypt

Brad Geagley

Contents

INTRODUCTION

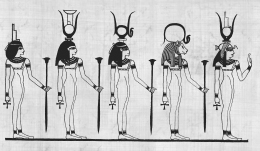

THE GODS

WILL

NOT WAIT

FOLLOWER

OF SET

THE

SERVANTS

OFTHE PLACE OFTRUTH

OPEN

YOUREYES

STREET

OF DOORS

THE

SEERESS OF

SEKHMET

HOUSE OF

ETERNITY

THE

GATES

OFDARKNESS

ABOUT

THE AUTHOR

SIMON &

SCHUSTER

Rockefeller

Center

1230 Avenue of

the

Americas

New York, NY

10020

This book is a

work of

fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are products

of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance

to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely

coincidental.

Copyright

© 2005

by Brad Geagley

All rights

reserved,

including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form.

SIMON& SCHUSTERand colophon are registered

trademarks

of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Library of

Congress

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Geagley, Brad,

date.

Year of the

hyenas /

Brad Geagley.

For my

mother,

Adell J.

Geagley

I am opposed

to the

increasingly longer and ever more gushing forms of author “thank you”

pages. Too often they sound like Oscar acceptance speeches and not like

something that belongs in a book. However, I would be remiss not to

mention four persons who were very important in the creation of this

manuscript:

Judith

Levin, Esq.

, my lawyer, agent,

and lucky star.

Michael

Korda

,

my esteemed editor,

who kept pulling me from the edge by pounding into my head the

following two phrases: “Mystery, Brad, not history,” and “More

Sherlock, less Indiana Jones.”

Carol Bowie

, Michael’s assistant;

as Judy said, it takes a brave woman to accept a manuscript in a

laundry room.

Frank Russo

, who, along with

Michael, read every word of

Hyenas

as it was being

written. Real estate may be his profession, but words are his art.

Thank you, all.

THOUGH

Year of the Hyenas

is a work of fiction,

the mystery depicted in the book is based on history’s oldest known

“court transcripts,” the so-called Judicial Papyrus of Turin, the

Papyrus Rifaud, and the Papyrus Rollin.

The year is

1153bce . The pyramids are

already fifteen

hundred years old, King Tut-ankh-amun has been dead for two hundred

years, and Cleopatra’s reign will occur over a thousand years in the

future. To the north, Achilles, Ajax, and Menelaus are battling the

Trojans for the return of Helen.

Most of the

characters

in this book are modeled after those people who lived at the time and

participated in the events. Ramses III, “the last great pharaoh,” ruled

Egypt with the aid of Vizier Toh, while at the Place of Truth the

tombmakers Khepura, Aaphat, and Hunro lived in homes that can still be

visited today. We even know that one day Paneb really did chase

Neferhotep up the village’s main street.

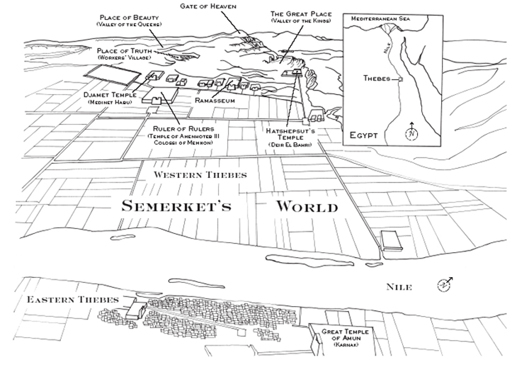

Though I have

simplified Egyptian spellings and names for the modern reader, I have

chosen to call certain temples and cities with the names used by the

Egyptians themselves. Medinet Habu thus becomes Djamet Temple, Deir el

Medina becomes the Place of Truth, the Valley of the Kings becomes the

Great Place, and so on. The exception to this is the city of Thebes, a

name too magnificent in itself to change to the more correct Waset.

Brad Geagley

WILL NOT

WAIT

HETEPHRAS LIMPED FROM HER PALLET

TO THEdoor

of her house like an old arthritic monkey. She pulled aside the linen

curtain and squinted to the east. Scents of the unfurling day met her

nostrils. Sour emmer wheat from the temple fields. The subtler aroma of

newcut barley. Distant Nile water, brown-rich and brackish. And even at

this early hour, someone fried onions for the Osiris Feast.

The old

priestess’s

eyes were almost entirely opaque now. Though a physician had offered to

restore her sight with his needle treatment, Hetephras was content to

view the world through the tawny clouds with which the gods had

afflicted her; in exchange they had endowed her other senses with

greater clarity. Out of timeworn habit she raised her head again to the

east, and for a moment imagined that she saw the beacon fires burning

in Amun’s Great Temple far across the river. But the curtains fell

across her sight again, as they always did, and the flames burnt

themselves out.

She pitied

herself for

a moment, because as priestess in the Place of Truth she could no

longer clearly view the treasures wrought in her village—decorations

for the tombs of pharaohs, queens, and nobles that were the sole

industry of her village of artists; pieces that lived for a smattering

of days in the light of the sun, then were borne to the Great Place,

brought into the tomb, and sealed beneath the sand and rock in darkness

forever.

Hetephras

unbent her

thin, bony spine, firmly banishing self-pity. She was priestess and had

to perform the inauguration rites for the Feast of Osiris that morning.

At Osiris Time, the hour for speaking with the gods was at the very

moment when the sun rose, for it was then that the membrane separating

this life and the next was at its most fragile, when the dead left

their vaults to gaze upon the distant living city of Thebes, girded for

festival.

Though she had

been a

priestess for over twenty years, Hetephras had never seen any shape or

spirit among the dead, as others said they had. She was an unsubtle

woman who took her joy from the simple verities of ritual, tradition,

and work. She believed with all her heart the stories of the gods, and

put it down to a fault in herself that never once had they revealed

themselves to her. Her husband, Djutmose, had been the spiritual one in

the family, having been the tombmakers’ priest when he married her.

When he died in the eleventh year of Pharaoh’s reign, the villagers

chose Hetephras to continue his duties; they had seen no reason to

search elsewhere.

Hetephras

sighed. That

was many years ago. Soon her own Day of Pain would come, as it must to

all living things, and she would be taken to lie beside Djutmose and

their son in their own small tomb. Perhaps it was only the morning

breezes that made her shiver.

She limped to

a large

chest in her sleeping room. On its lid, flowers of ivory and glass

paste entwined, while voles and crows of pear wood worried the curling

grapevines of turquoise and agate. It had been made by her husband. In

addition to his priestly duties, Djutmose had been a maker of

cupboards, caskets, and boxes for Pharaoh, and he had fashioned these

simple images knowing they would please his simple wife. She cherished

this casket now above all else she owned; it would be buried with her.

From this

chest

Hetephras plucked her priestess garb: a sheath of linen, white;

pectoral of woven wire, gilded; and a bright blue wig of raffia fibers

in the shape of vulture wings. Then she carefully packed the oil and

sweetmeats the gods so loved into an alabaster chalice. Thus attired

and burdened, she waited at her stoop for Rami, the son of the chief

scribe. It was Rami who had been appointed to guide her to the shrines

on these feast days.

But there was

no sign

of the boy. Hetephras stood waiting patiently for him, skin prickling

against the cool air of morning. Her thick wig made a comfortable

pillow as she leaned against the doorframe. Her eyes closed, just for a

moment… and the old lady was carried away into nodding forgetfulness by

the quiet and the breezes. She was brought awake again by the subtle

warming of her skin.

She looked

around,

startled, sniffing the air. Irritation and panic made her heart beat

faster. It was fast becoming full dawn! She would miss the appointed

time for the offering! The gods would blame her, and in turn would

become churlish with their blessings.

Damn Rami!

Where was

he? Sleeping with the shroud-weaver Mentu’s little slut, no doubt. She

had heard them together before, her ears keen to catch their shared

laughter and, later, their moans. The youngsters of the village often

used the empty stable next to Hetephras’s house as a trysting place—as

did some of the adults. The old priestess murmured dismally to herself

that a generation of sluggards and whores was poised to inherit Egypt.

Hetephras

decided to

go alone to the Osiris shrine. It was the most distant of all the

shrines and chapels she tended, and when she thought of the effort it

would cost her, half-blind as she was, her heart thumped with fresh

anger toward Rami.

Damn him! She

would

give him a tongue-lashing in front of his parents, that’s what she

would do—in front of the whole village!