Yoga for a Healthy Lower Back (4 page)

Read Yoga for a Healthy Lower Back Online

Authors: Liz Owen

Generally speaking, when you practice yoga poses (asanas), your breath should be full, smooth, and rhythmic, taking as long to inhale as you do to exhale. In my classes, I advise students to use their breath this way: “A strong breath for a strong pose, a soft breath for a soft pose.” That means that when you are practicing a pose that takes a lot of energy, such as a standing pose or a backbend, you should breathe very deeplyâideally, in a softly audible wayâto help your body move into the pose, to support your

body while you are in the pose, and to help you to come out of it. Remain mindful of your breath, especially in challenging poses, because you may discover a tendency to hold it when your body is working hard. When that happens, gently bring your breath back into your body with a deep, even, audible inhalation and exhalationâyou'll feel a big, immediate difference in how you experience the pose. Remember, though, when you are in a restful or meditative position, to let your breath become soft and quiet, encouraging your body and mind to relax.

When you focus your mind on your breath as well as on your body, your mind is drawn inward. It learns to observe, witness, and become present to the sensations in your bodyâespecially, for our purposes, the critical messages your lower back is trying to tell you about its condition and what will help it to come into wellness. A natural, full flow of breath can help to open tight areas, release tension, and bring life force (prana) into its full expression in your body.

The breath work (pranayama) exercises I will introduce in this book are meant to help you cope with chronic pain and the emotional stresses that come along with it. Much of the pranayama practice you'll learn in this book is meant to elicit the “relaxation response” I discussed earlier. When your emotions lose their charge and calm down, you can create a positive dialogue with your body and your pain, instead of living with the fear and anxiety that often accompany chronic pain. Remember, you can practice pranayama exercises whenever you feel pain or are mentally or emotionally charged or strained . . . and whether you're on and off your yoga mat. Once you connect with the power of your breath, you'll carry a self-sustaining treasure trove of wellness and life force wherever your life takes you.

Now let's learn one of the most powerful (yet accessible) pranayama practices I know ofâOcean Breath. You'll see this breath a number of times throughout this book, and I hope that it can become a go-to practice whenever you need to come into control of your breath and direct it toward your emotional or physical well-being.

Ocean Breath is called Ujjayi Pranayama in the yogic texts.

Ujjayi

means “upward victory,” which is quite descriptive of how this breath feels and looks in your body, because when you practice it, your lungs are fully expanded and your chest lifts and broadens, like a mighty conqueror.

24

Yet the name Ocean Breath is lovely and apt as well, because as you will hear, it sounds like a gentle ocean wave breaking in the distance. You will create this sound by very slightly and gently narrowing the space between your

vocal cords. Sometimes it's hard to know if you're actually doing that, but you can tell you've got it when both your inhalations and your exhalations take on a soft, rich, resonant, audible vibration.

To find Ocean Breath, take a long inhalation and create an audible sighing sound as you exhale through your mouth. Now close your mouth and when you exhale again, do so this time through your nose. Can you create a similar sighing sound? Practice the sighing sound in both your inhalations and exhalations, breathing through your nose, until your breath becomes long, deep, and full. Let your breath move into and out of your body like a gentle ocean wave lapping at a peaceful shore.

Be sure to pay mindful attention to the quality of your breath and how your body and mind feel during your practice. You're good to go as long as your breath is long, smooth, and resonant. But if your hear strain in your breath, if it “catches,” or if your body starts to tense up, it's time to let go of Ocean Breath and return to normal breathing. You can take a couple of regular breaths and then return to practice Ocean Breath for a few more rounds.

H

OW

T

O

S

TAND

Your posture, or how you hold your body in a standing position, says a lot about you, from the state of your self-esteem to the likelihood that you are suffering from lower back pain. Standing up straight, strong, and tall can make all the difference in the image you projectâboth outward to the world and inward to your own self-image.

There are many factors that determine your posture. Some of these are beyond your control, such as the bone structure and body shape that you inherited from your family or that were set by how you were positioned in your mother's womb. Other factors are only slightly more under your control, such as the stresses and strains of your job or daily routine at home. Other factors that affect your posture are more functional, such as the mobility of your hips, spine, and shoulders; the muscle tone of your legs, hips, abdominal wall, and back; and the way emotional stress manifests in your body.

I mentioned self-esteem before, and on that note, I'm sure you're aware of what can easily happenâespecially in your upper chest and shouldersâwhen you experience challenging emotions such as insecurity, sadness, or grief, not to mention the mental and emotional stressors that often accompany chronic pain. It's no coincidence that your upper back and shoulders hunch forward and your upper chest caves inward during times of stress or pain. At those moments, we tend to instinctively close our hearts, both literally and figuratively, to protect ourselves. As you practice yoga, you will find physical stability that will help carry you through stress and chronic lower back pain. Because your body and mind are inextricably connected, you may also find that bringing stability into your body encourages emotional stability. From that stable place, you may find yourself better able to face the stresses and strains of everyday lifeâwith your spine lifted and your heart open.

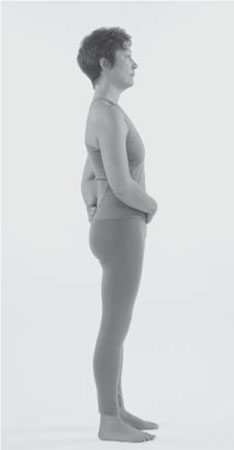

FIG. 1.1

Now that you understand the importance of your baseline standing posture, it may not surprise you to learn there is a yoga pose for simply standing up straight. It is called Mountain Pose, or

Tadasana

in Sanskrit (

fig. 1.1

). It is one of those poses you can practice at the bus stop in the morning, in front of a mirror before bed, or waiting in line at the ATM. Standing up in an aligned, mindful way is available to you wherever you are.

Try Mountain Pose now: Stand with your feet grounded to the earth while your spine and the crown of your head elongate up toward the sky. Visualize the natural centerline of your body, from front to back, which passes through the center of your ankles, knees, hips, and shoulders. Bring your ears and the crown of your head into alignment with your shoulders. Imagine your strong, long centerline passing right through the center of your pelvic girdle; your sacrum and thoracic spine curve gently backward from it, your lumbar and cervical spines curve inward to meet it, and the base of your skull is centered on it.

Take a moment to look at yourself from the side in a mirror and see if you can find this alignment. Are your hips balanced over your legs, or do they sway forward or backward? Are your shoulders aligned over your hips, or are they rounded forward or thrown back? Are your ears set squarely over your shoulders?

Practice Mountain Pose again, this time with your back body against a wall. Place your hips and your shoulders snugly on the wallâroll your shoulders back until your shoulder blades rest as much as possible against the wall. Notice what happened in your lower back when you took your shoulders backâdid it keep a long, gentle curve, or did it overarch forward and throw your abdomen away from the wall?

Finally, take the back of your head to the wall to bring your shoulders, ears, and crown of head into alignment with your spine. Be sure that your chin is parallel to the floor so the back of your neck stays long.

You are now in your natural alignment. Does your body feel different from how it normally does when you “stand up straight?” This may be a very different experience of what it means to stand in postural alignment, even when you practiced Mountain Pose just a moment ago, without the support of a wall.

In your supported Mountain Pose, close your eyes for a moment and feel stability in your legs and hips. Visualize the long, gentle curves of your lower back, middle back, upper back, and neck as they rise out of your sacrum and climb up to the base of your skull, like strong, limber vines that support your rib cage, shoulder girdle, and head. Take a big, deep breath into your broad and open heart!

FIG. 1.2

Now step away from the wall and see if you can maintain the alignment you just discovered and create “neutral hip position,” which establishes an upright and balanced position of your pelvic girdle and centers your hips over your thighs (

fig. 1.2

). We'll come back to this position many times throughout the bookâyou can experience it by creating the following actions in your pelvis and legs:

â¢Â  First draw your tailbone down the wall, then scoop it in and up.

â¢Â  Roll your upper thighs slightly inward.

â¢Â  Press your front thighs back toward the wall.

â¢Â  Lift your frontal hip bones up toward your waist.

â¢Â  Hug your abdominal wall toward your spine.

You'll see many references to neutral hip position throughout the book, because it creates stability in your hips, alignment in your sacrum and lumbar, and a healthy base from which your spine can come into its gently curved profile.

Relish your neutral hips and aligned spine for a moment. Carry the feeling with you throughout your day, and remember: when your spine is in alignment, it is strong and flexible, and your bodyâespecially your lower backâwill move with ease and grace. Repeat Mountain Pose at a wall whenever you feel slouchy, collapsed, or when you have the blues from

chronic pain, as a reminder of what your body can and will feel like when it's in its natural alignment. Use it as a reminder, as well, of what it can feel like to align all the aspects of yourself: your body, your breath, your mind, your emotions, and your deepest, most essential core.

S

ELF

-A

SSESSMENTS:

A

RE

Y

OUR

H

IPS

A

LIGNED?

Your hips move back and forth and up and down with every step you take. In addition, your hip bones rotate up and back, and forward and down. Your pelvic girdle is vulnerable to the stresses and strains that come with all of their movements, especially when the myofascia around them is imbalanced, tight, or weak. The result is that your hip bones and sacral joints reform into imbalanced positions. Imbalanced alignment isn't always a direct cause of lower back pain, although it sometimes is, but it can cause your lower back to become vulnerable to injury, which then produces back pain.

25

Now that you've established the natural alignment of your body in Mountain Pose, you can do three simple tests to determine if your hip bones are aligned, or whether one is higher or lower, or rotated up or down. And you'll explore the effect of imbalanced sacral joints on your hip bones. You'll use your findings in chapters 2 and 3 to help realign and balance your hips and sacral joints.

First, you'll find your ASIS, or the anterior superior iliac spine (

fig 1.3

). This comprises the prominent knobby points on the front of your hip bones. Stand in Mountain Pose in front of a mirror with your fingers on your front hip bones. Bend your knees and come into a forward bend position. Massage the front of your hips with your fingers until you find the ASIS points, which are right above the crease of your front groins, and place your index and middle fingers on them. Now slowly stand up, straighten your legs, and look at your hips in the mirror. Are your fingers, and thus your hip bones, even with each other, or is one side higher than the other? Now check for rotationâis one hip bone closer to the mirror than the other?