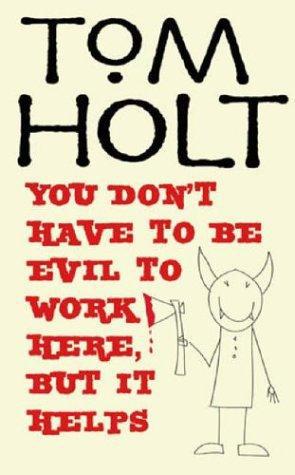

You Don't Have To Be Evil To Work Here, But It Helps

Read You Don't Have To Be Evil To Work Here, But It Helps Online

Authors: Tom Holt

Tags: #Humorous, #Fantasy, #General, #Fiction, #Magic, #Family-owned business enterprises

YOU DON’T HAVE TO BE EVIL TO WORK HERE, BUT IT HELPS by TOM HOLT

CHAPTER ONE

Three weeks, and still nobody had the faintest idea who they were. There were rumours, of course: they were Americans, Germans, Russians, Japanese, an international consortium based in Ulan Bator, the Barclay brothers, Rupert Murdoch; they were white knights, asset strippers, the good guys, the bad guys, maybe even Kawaguchiya Integrated Circuits operating through a network of shells and holding companies designed to bypass US anti-trust legislation. Presumably the partners had some idea who they were, but Mr Wells hadn’t been seen around the office in weeks, Mr Suslowicz burst into tears if anybody raised the subject, and nobody was brave and stupid enough to ask Mr Tanner.

‘We bloody well ought to be able to figure it out for ourselves,’ declared Connie Schwartz-Alberich from Mineral Rights, not for the first time. ‘I mean, it’s a small industry, the number of players is strictly limited. Only’ She pulled a face. ‘Only I’ve been ringing round - people I know in other firms - and everybody seems just as confused as we are. You’d have thought someone would’ve heard something by now, but apparently not. It’s bloody frustrating.’

Thoughtful silence; a soft grunt of disgust from Peter Melznic as half of his dunked digestive broke off and flopped into his tea.

‘I still reckon it’s the Germans,’ said Benny Shumway, chief cashier. ‘Zauberkraftwerk or UMG. They’re the only ones big enough in Europe.’

‘Unlikely,’ muttered the thin-faced new girl from Entertainment and Media, whose name nobody could remember. ‘I worked for UMG for eighteen months - it’s not their style.’

For some reason, the new girl’s statements were always followed by an awkward silence, as though she’d just said something rude or obviously false. Unfortunate manner was the generally held explanation, but it didn’t quite ring true. Peter Melznic was on record as saying that she gave him the creeps - coming from Peter, that was quite an assertion - but even he was at a loss to explain exactly why.

‘I don’t think it’s anybody in the business,’ the new girl went on. ‘I think it’s someone completely new that none of us has ever heard of. Possibly,’ she added after a moment’s reflection, ‘Romanians. It’s just a feeling I have.’

‘I don’t care who it is,’ Connie Schwartz-Alberich lied, ‘so long as it’s not Harrison’s. I couldn’t stand the thought of having to take orders from that smug git Tony Harrison. He was a junior clerk here once, believe it or not, years ago.’

Benny Shumway frowned. ‘Is that right?’

Connie nodded. ‘It was just before I got sent out to the San Francisco office. He started off in mineral rights, same as everybody. He was an obnoxious little prick even then.’

Benny shrugged. ‘I don’t think it’s Harrison’s,’ he said. ‘I happen to know they’re in deep trouble right now. In fact, if it wasn’t for the bank bailing them out’ He paused, and frowned. ‘Anyhow, it’s not them. Not,’ he added, standing up, ‘that it’s something we can do anything about. And so far, admit it, they’ve not been so bad.’

Connie snorted; Peter scowled; the new girl was staring in rapt fascination at a picture on the wall. She did things like that. Benny glanced at his watch and sighed. ‘Time I wasn’t here,’ he said.

Left alone with four empty mugs and her thoughts, Connie tried to get back to the job in hand, but she couldn’t concentrate. Benny had been right, of course. Whoever they were, they’d bought the company, and she and her colleagues went with the rest of the inventory, the desks, chairs, VDUs and stationery at valuation; it’d be entirely unrealistic to classify them as part of the goodwill. It was, she couldn’t help thinking, a funny old way to run a civilisation, but she’d become reconciled over the years to the fact that her consent was neither sought nor required. Five more years to retirement; a long time to hang on, but at her age she had no choice. Whoever they were, accordingly, they had her heart and mind.

Just for curiosity, she turned her head and looked at the picture, the one that had apparently fascinated the new girl. Poole Harbour, in watercolours, by Connie’s brother Norman. There vas something odd about that girl, but for the life of her Connie couldn’t quite pin down what it was.

She picked up a stack of six-by-eight black-and-white glossy prints. Most people would’ve been hard-pressed to say whether they were modern art, the latest pictures of the surface of the Moon sent back by the space shuttle, close-ups of wood grain or the inside view of a careless photographer’s lens cap. She picked one off the top of the stack, closed her eyes and rested the palm of her hand on it. Harrison’s, she thought, and scowled.

The phone on Connie’s desk rang, startling her out of vague recollections of Tony Harrison as a junior clerk asking her in crimson embarrassment where the men’s bogs were. As she lifted her hand off the photograph to answer it, she noticed a faint cloud of moisture on the surface of the print. Ah, she thought, I must be worried.

‘Cassie for you.’

‘God,’ Connie sighed. ‘All right.’

The usual click, and then: ‘Connie?’

‘Cassie, dear.’

‘I’m stuck.’

‘What, again}’ Connie closed her eyes. I-will-not-be-brusque. I-was-young-and-feckless-once. No, she reflected; I was young, but I didn’t keep getting stuck all the bloody time. ‘Listen,’ she said pleasantly, ‘it’s just a tiny bit awkward at the moment, do you think you could possibly hang on there till lunch?’

‘No,’ Cassie squeaked. ‘Look, I’m stuck, you’ve got to’

‘All right,’ Connie sighed. ‘Tell me where you are, and I’ll come and get you.’

She wrote down the directions on her scratchpad, the corners and edges of which she’d earlier embellished with graceful doodles of entwined sea serpents. ‘Please hurry,’ Cassie pleaded urgently. ‘Sorry to be a pain, but’

‘Be with you as soon as I can,’ Connie said, and put the phone down. Bugger, she thought. It was, of course, only natural that the younger woman should have chosen her as her guide, role model and mentor. Even so. She glanced down at the pile of prints; she could always take them home and do them this evening, it wasn’t as if she had anything else planned. Somehow, that reflection brought her little comfort. She stood up, took down her coat from behind the door, and left the room.

To get out of 70 St Mary Axe without (a) official leave (b) being seen by Mr Tanner, assuming you’re starting from the second floor back, you have to sneak across the landing into the computer room to the rear staircase. This will bring you out in the long corridor that curls round the ground floor like a python, and of course you’ll pass Mr Suslowicz’s door on your way. But that’s all right, because Cas Suslowicz

‘Connie,’ said Mr Suslowicz, poking his head round his office door. ‘I was just coming to look for you.’

‘Ah,’ Connie replied.

‘You’re not busy right now, are you?’

Yes. ‘No,’ Connie said, in a neutral sort of voice. ‘I was just on my way to the library, as a matter of’

‘You couldn’t do me a favour, could you?’

It was, always, the way he said it. You wouldn’t expect it to look at him; he had vast shoulders, gigantic round red cheeks and a dense black beard whose pointed tip brushed against the buckle of his trouser belt. Somehow, however, he managed to sound like a very small child who’s been separated from his parents at a fairground.

Cassie, stuck, awaiting her with frantic impatience. ‘Sure,’ she said, ‘what can I do for you?’

‘It’s these dratted specifications,’ said Mr Suslowicz; and Connie asked herself if she’d ever heard him use coarse or profane language. Buggered if she knew. ‘Some of it I can understand, but a lot of it’s horribly technical. It’d take me a week to look it all up, and even then I probably couldn’t make head nor tail of it. Do you think you could possibly??’

‘Of course,’ Connie said brightly. ‘Get Nikki to leave it on my desk and I’ll look at it first thing after lunch.’

‘Ah.’ He could look so sad when he wanted to. ‘Actually, it’d be a tremendous help if you could just cast your eye over it terribly quickly now. I’ve got the client coming in at three, you see.’

Connie thought quickly. Poor stuck Cassie; but stuck, by definition, means not likely to be going anywhere in a hurry. And maybe, just possibly, having to wait an extra forty minutes might encourage her to look where she was going, the next time.

‘No problem,’ Connie said. (And she thought: just five years to go, and then they can all get stuck permanently, with or without reams of incomprehensible technical jargon, and it won’t be any of my concern.) ‘How’s your back, by the way?’

‘Much better,’ Mr Suslowicz replied. ‘My own silly fault, of course. I just can’t get used to the fact that I’m not able to do the kind of stuff I could handle twenty years ago.’ He grinned sheepishly - he must have stupendous lip muscles, Connie reflected, In order to lift that bloody great big beard - and held the door for her.

One glance at the wodge of single-spaced typescript reassured Connie that Cas wasn’t just being feeble. It was pretty advanced stuff, all about atomic densities and molecular structures, and she was rather proud of the fact that she could understand it.

Explaining it, on the other hand ‘Quite a job you’ve got on here,’ she said. ‘New client?’

Cas nodded; she managed not to look at the tip of his beard massaging his crotch. ‘Quite a catch, if we can keep him happy,’ he said. ‘Hence the urgency.’

Connie avoided his gaze. ‘Friends of the new management?’ she asked, trying and failing to sound casual.

‘Yes and no.’

She waited a full half-second, then said, ‘Ah’ and turned her attention back to the technical drivel. ‘Well,’ she said, ‘it’s like this. Imagine the Einsteinian spatio-temporal universe is a globe artichoke’

Whether or not Cas really understood what she’d endeavoured to explain to him, he let her go an hour later, thanking her profusely and apologising for taking up so much of her time. That was the infuriating thing about Cas Suslowicz, she thought, as she hurtled toward the front office. There ought to be a law, or something in the European Declaration of Human Rights, about bosses not being allowed to be nice. It went against a thousand years of tradition in the field of British industrial relations. Of course, she reminded herself as she pushed through the fire door, Cas Suslowicz is nominally Polish

‘Early lunch?’ snapped the girl behind the reception desk. She was slight, slim, blue-eyed, red-haired and to all appearances not a day over twenty-two. She was also Mr Tanner’s mother.

‘Don’t talk to me about lunch,’ Connie counter-snapped. No chance of even a fleeting sandwich, if she had to go and unstick Cassie and be back in the office by two p.m. The explanation wasn’t, however, something that she could share with a boss’s mother. ‘If Tillotsons call, take a message,’ she added, and lunged out into the street.

Poor stuck Cassie - Connie scowled. Impossible, in the circumstances, to take a taxi to Charing Cross and put in a pink expenses chit to get the money back off the firm; which meant that either she’d have to pay for a taxi out of her own money, or take the slow but cheaper Tube. Well, she thought; Cassie’s been there a fair old while already, another twenty minutes won’t kill her. As a sop to her conscience, Connie increased her pace to a swiftish march (new shoes, heel-tips not yet ground down to comfortable stubs). Halfway down St Mary Axe, however, someone called out her name and she stopped.

‘Connie Schwartz-Alberich,’ he repeated. ‘You haven’t got a clue who I am, have you?’

He was short, slim, thin on top, glasses, fifty-whatever; Burton’s suit, birthday-present tie. His voice, however, came straight from somewhere else, long ago and very far away. It couldn’t be.

‘George?’

He grinned. Voices and grins don’t decay the way other externals do. ‘Hellfire, Connie,’ he said, ‘you haven’t changed a bit.’

‘Balls,’ she replied demurely. ‘You have, though.’

‘True.’ He frowned. ‘I was going to say, fancy meeting you here, but’ His frown deepened. ‘Don’t say you’re still stuck at JWW.’

‘Yes.’

‘My God.’ He shrugged. ‘Why?’

‘Too old to get a decent job, of course. How about you? Still .it M&F?’

He laughed. ‘Not likely,’ he said. ‘I went freelance - what, fifteen years ago. Got my own consultancy now.’

‘Doing all right?’

‘I guess so.’ His grin made it obvious that he was being modest. For over a second and a half, Connie hated him to death. ‘Better than the old days, anyhow. Look, is it your lunch hour, or can you skive off whatever you’re doing?’

Poor Cassie, stuck; on the other hand, George Katzbalger, apparently returned from the dead. ‘Oh, go on,’ she said. ‘Let’s go and have a pizza.’

He looked puzzled. ‘A what?’

‘Pi’ She remembered one of the salient facts about George. ‘You choose,’ she said.

‘Pleasure. There’s this really rather good little Uzbek place just round the corner. Know it?’

‘Uzbek?’

‘Big bowls of rice with little bits of stuff in it.’

‘Yes, all right. But I can’t be too long, I’ve got to go and rescue someone before one-fifteen at the latest.’