You Majored in What? (7 page)

Read You Majored in What? Online

Authors: Katharine Brooks

Your Wandering Map is just the start of your process and soon you will be combining the information you’ve uncovered in this chapter with the knowledge you’ll acquire in the next few chapters to begin designing your plans for a captivating and compelling future.

Before you leave your Wandering Map, consider the following questions:

1. If you’re having trouble seeing your themes, try asking yourself these questions: “What would happen if a miracle occurred tonight and suddenly I could see the themes? What do I think they would be?”

2. What two or three items are you most proud of? What skills or behaviors did you use to accomplish them? Can you begin thinking of ways to use those skills or behaviors now or in a work setting?

3. On a scale of 1 to 10, with 1 being least important and 10 being most important, which theme would you rank as the most important? Why?

4. If you knew you couldn’t fail, which one of these themes would you keep pursuing?

5. What theme would you like to take a step toward pursuing in the next twenty-four hours? What step would you take?

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

WISDOM BUILDERS

1.

GETTING THE MOST FROM YOUR STUDY—ABROAD EXPERIENCE: WHAT GRADUATES HAVE DISCOVERED

Many students and recent graduates include their study-abroad experience in their Wandering Maps. When surveyed about their college experiences, graduates almost always rank their study-abroad experience as one of the best and most fulfilling times in their lives. They cite the unexpected benefits they received from the experience and the many skills and talents they acquired, almost without realizing it. Here’s a list of the common strengths graduates say they acquired through the study-abroad experience:

• Established rapport with individuals from other cultures

• Functioned well in ambiguous situations and handled difficult situations

• Achieved goals (despite lots of challenges)

• Showed initiative and took risks

• Managed time well enough to both study and travel

• Responsible for all personal actions (no one else to rely on)

• Learned the language quickly

• Learned to be comfortable while relocating often in a job

• Learned through listening and observing

• Developed good decision-making skills . . . after making some errors

How might this list of skills interest an employer?

Can you think of some skills you derived, or might get, from studying abroad? Make some notes here: ________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________

2. HOW DO MY RELATIVES FIT INTO MY CAREER PLANS?

Another common component of a Wandering Map is the influence of family. Your parents and other relatives can be influential sources of information and attitudes about careers. Whether it’s a family business or career such as medicine, performing arts, and the law, it’s not uncommon for family traditions to develop around careers. What you need to decide is whether your family’s career field works for you. Here are some questions to consider as you think about the influence of your family:

• What do my parents say about their work?

• Did they choose their careers or did circumstances influence them?

• Would they do the same work again?

• Is there a career field that runs through my family?

• Am I interested in continuing this family tradition?

• What will happen if I do or don’t follow the tradition?

• What suggestions or advice have my parents given me about my career?

• What are my siblings doing?

• Do they enjoy the careers they’re in? Why or why not?

• What advice or guidance have they given me?

• What assumptions about work might I have made based on what I heard or observed in my family?

Summarize any significant messages you’ve received about work from your family: ________________________________________

______________________________________________________

______________________________________________________

3. HOW DO I DEFINE SUCCESS?

When you look at the experiences on your Wandering Map that you consider successful, how did you define success? Did it involve winning? Helping others? Achieving?

How might you define success in the future? Complete any of these sentences that appeal to you (no need to do them all):

As my life progresses, I will consider myself successful when I

HAVE THIS JOB TITLE: ___________________________________

OWN ____________________________________________________

RETIRE AT AGE ____ IN ______________________ (LOCATION)

USE MY TALENT IN________________ TO ___________________

AM IN LOVE WITH _______________________________________

SPEND MY TIME _________________________________________

VOLUNTEER TO __________________________________________

RECEIVE AN AWARD FOR _________________________________

AM ASKED FOR MY AUTOGRAPH BECAUSE I ________________

HAVE PURSUED __________________________________________

DO______________________________________________________

HAVE__________DOLLARS IN THE BANK OR IN INVESTMENTS

FILL IN THE BLANKS WITH YOUR OWN IDEAS:

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

Now, reward yourself for the hard work you’ve already done, and relish the order you’re finding in the chaos. You’ve already mined your past for gold; in the next chapter you’re going to get the most from an extremely valuable possession: your brain.

MENTAL WANDERINGS

YOUR MIND CAN TAKE YOU ANYWHERE OR NOWHERE

The universe is full of magical things, patiently waiting for our wits to grow sharper.

—EDEN PHILLPOTTS,

A SHADOW PASSES

THE VALUE OF THINKING

Two college deans stepped off the curb to cross a street when a pickup truck with a gun rack whizzed by, slowing down just long enough for the passenger to lean out the window, look at the two men, and yell, “Hey, smart guys!” before driving on. The two deans looked at each other, unsure how to react. Was that an insult or a compliment?

O

ur society sends mixed messages about being smart. From popular movies such as

Dumb and Dumber,

the TV show

Jackass,

and even book series such as _______

for Dummies,

we seem to be much more comfortable putting down our thinking power than promoting it. This tendency to downplay intelligence and thinking even rubs off on clearly intelligent career fields like Web development. A popular Web design book title,

Don’t Make Me Think,

succinctly sums up the prevailing philosophy about Web sites: the worst thing you can do is design a Web site that will require people to think. Part of the problem seems to be that people simply don’t have time to think anymore. We need short and quick Web sites and books that spell out everything so we don’t have to waste our time thinking.

College is supposed to be a time for thinking, but again, if you watch movies about the college scene (

Animal House

anyone?), you sure wouldn’t know it. The students who are serious and thoughtful never seem to be the cool or popular ones. So it’s not surprising that when I ask my students in class what mindsets or types of thinking they’ve developed through their classes, I get blank stares. They’ll tell me they haven’t had time to think about it. Ironic, isn’t it?

Does the “don’t make me think” philosophy mirror your time in college? Have you been acquiring a lot of knowledge and information without thinking of its value? Are you finding it hard to articulate to employers what you have learned or are not even sure why they’d want to know about your classes? After all, those job openings for philosophers or sociologists have been few and far between.

There’s no mixed message in this chapter—your knowledge and thinking skills

are

your power. Employers are begging for intelligent workers who possess and use the right mindsets: specific ways of thinking. The way you choose to think about your classes, your experiences, and your job search is the key to your success in the hiring process and beyond. But good luck finding a career book that gives thinking or mindsets more than a cursory glance.

In the last chapter you developed your Wandering Map, which highlighted past achievements, talents, and themes running through your life. In this chapter we’re going to

dig deeper and look specifically at the brain power behind those talents and themes

: the mindsets you’ve developed that will help you ace your interview, get a job, and move up in whatever career path you follow. And if you haven’t developed all of these mindsets yet, you will learn enough to start adding them to your repertoire of skills and talents.

What if you possessed a secret power that would change your job search completely? What if that power was in your mind?

It’s time to get wise.

RIGHT MIND:THE KEY ELEMENT OF GOOD THINKING

We don’t think of thoughts as tangible, because we can’t see them with our eyes any more than we can see the electricity that powers our computers or the vibrations that travel from our cell phones. Yet your e-mail arrives and your friend answers the cell phone. Thanks to increasingly powerful medical technology, we are beginning to “see” and measure thoughts—or at least see the parts of the brain that light up when certain thoughts or images are active. And as a result, our knowledge of the brain and how it thinks is growing exponentially. Your thinking skills are as real and identifiable as your more visible skills, such as athletic, musical, or artistic talents.

If you consider your thoughts to be just as tangible as the book you’re holding, then you can examine them and make deliberate choices in how you think. The field of cognitive behavioral psychology has demonstrated that how we think directly influences how we feel. When our attitude changes, our behaviors change, and this in turn influences our performance. So how you choose to think about your classes, experiences, the job search, and your job directly affects your success before and after graduation.

When you change the way you look at things, the things you look at change.

—WAYNE DYER,

THE POWER OF INVENTION

Good thinking will help you change how you interpret a situation. Zen philosophers have a nice phrase for good thinking: right mind. Right-mind thinking creates a positive chain of success in whatever endeavors you pursue even when you’re in less than desirable situations. Right-mind thinking doesn’t mean you ignore challenges or pretend that something bad is really good. Instead, you take what is challenging and find a way to mentally approach the challenge so that ultimately you succeed in the situation.

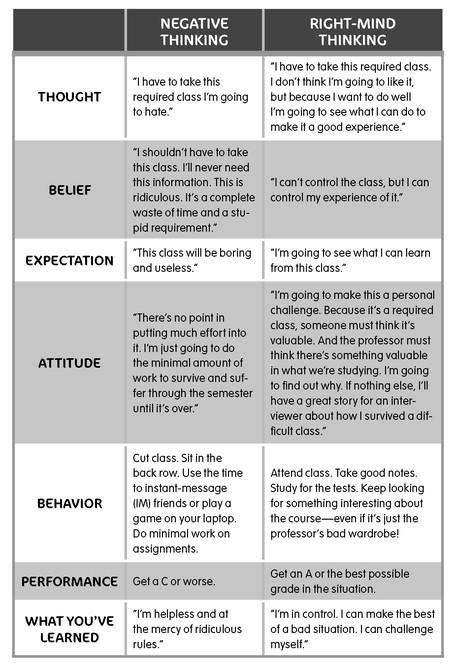

Let’s look at this in terms of a common student situation: you’re required to take a class you really don’t want to take. There are two tracks your thinking can follow:

Notice that at no time did the right-mind thought process become Pollyannaish or lapse into happy talk. The thinker didn’t lie to herself and say. “Oh, this class will be wonderful. I can’t wait to take it. I love the professor.” Quite the opposite. The thinker took a realistic perspective: “The class is what it is. I can choose to suffer through it or I can make the best of it.”

Aside from causing pain and leading you down a path to a poor outcome and uninspiring future, negative thinking has a particularly fatal flaw: it presumes you are a fortune-teller. How do you know you’ll never need the information from that class? Maybe a required science class sounds awful now, but what if two years later you decide to become a psychologist and need that science knowledge to get better grades in your psych classes, ace the Graduate Record Examination (GRE), or get into a master’s degree program? How do you know that you won’t suddenly enjoy that class and end up majoring in the subject? The right-mind thinker understands the power of the butterfly effect and remains open to the possibility that something good might come from an experience. The Chinese philosopher Lao-tzu was on to something when he said, “Know that you don’t know. That’s superior.”