Your Brain and Business: The Neuroscience of Great Leaders (17 page)

Read Your Brain and Business: The Neuroscience of Great Leaders Online

Authors: Srinivasan S. Pillay

What this means (without having to memorize the brain regions) is that intuition is a “quick-and-dirty” fix—faster than deliberate thinking (because the brain’s emotional centers get a quick read) but not always as accurate. Early detection needs to be balanced with accuracy but should not be ignored.

Jane P., a client I once coached, listened to her “emotions” when she went for a job interview even though all other factors pointed in the opposite direction. She interviewed for a senior management position, which promised a significant pay raise, more flexibility, and more responsibility, all of which she wanted. The firm she interviewed with (a Fortune 500 company) really wanted to hire her. But as she walked around the building meeting people, she thought that she detected a “fear” or “threat” in the employees. She had no rational reasons, and although this was a crucial career move for her, she decided to turn down the offer because of the discomfort she felt. Her “intuition brain detectors” kept firing. She was therefore not surprised that a few months after she turned down the offer, the company “collapsed” and had a significant restructuring that would have left her—as a new hire—without a job. Her insula and ACC had provided information to her that was vital to her survival. It was fortunate for her that she was listening to these signals from within her brain.

•

Brain regions that integrate inputs and are deeply unconscious increase intuition.

Semantic coherence systems have also been shown to increase neural activity in heteromodal association areas (brain regions that integrate inputs to produce a coherent picture of the world) in the bilateral inferior parietal and right superior temporal cortex.

34

In another study, even without consciously knowing whether cues were rewards or punishments, people chose rewards over punishments, and this correlated with activity in the ventral striatum.

35

Thus, the reward center of the brain has ways to register unconscious information. You may not know why you make the choices you do, but your brain may “know” before you do.

•

Intuition may be automatic.

Other concepts related to intuition are mirror neurons (which automatically activate to represent another person’s movements, intentions, or feeling states).

36

The application:

How does knowing this information help you when working with leaders or managers? The following summary is what we can extract: (1) We have evidence that the brain does register information before you consciously know it—so pay attention to this and do not let go of an intuition. (2) These intuitions register in a few brain regions: mostly, the insula, OFC (cognitive flexibility region), and ACC (attentional center). Now we understand that knowing before you know is possible. (3) The brain processes information before a goal is known or before final data is known with what it has available to it. Later on, the accuracy of data improves; therefore, with intuition, in order to not let go, we can construct intuition maps and explore them (see

Chapter 8

). (4) If we have intuitions and ignore them, we may not drive explorations as far as we could early enough—the more information we give the brain’s navigator, the more likely we are to initiate an action. (5) Mirror neurons activate automatically so that you can read other people’s intentions and emotions. Coaching can help you learn how to use this knowledge without discarding it.

The Neuroscience of Body Language and Its Application to Thought

The concept:

We have referred to mirror neurons multiple times in this book. Mirror neurons are groups of brain cells that activate in specific brain regions when someone acts, intends, or emotes.

37

Thus, when somebody’s body moves, even if you are not consciously thinking about it, it is being represented in your brain. If it is awkward, you may not like the person, but the reality is that you are probably not liking what just got automatically registered in your

own

brain. Leaders should be aware that their body language automatically affects others,

and they would likely benefit from an increased awareness of this. Once this action is registered in your brain, it will likely stimulate related emotion areas as well.

Furthermore, a concept called “embodied cognition” has recently been introduced to the neuroscience literature. Essentially, this theory is based on the hypothesis that it is not just thoughts that create or cause movement, but movement itself can also create thoughts. That is, certain kinds of movement may contribute to insight or solving problems.

38

In fact, some researchers believe that it is not necessarily the emotion mirror systems that people share when they understand each other’s emotions, but a movement mirror system that then generates thoughts and emotions.

39

The application:

Reading body language occurs at multiple levels in the human brain. Reading of body language occurs automatically in the human brain in the mirror neuron system. This “reading” may stimulate thoughts and emotions within the brain of the observer. Also, we can change our patterns of thinking and insight by moving. The exact form of movement for any given problem is not yet known, but we do know that when we move, we can stimulate insight solutions to certain problems. Thus, coaches may prescribe exercise, or even, in the midst of problem solving, taking a motor break involving swinging the arms or stretching them. The idea here is to offer movement as a way of exploring (rather than knowing) that an insight may be enhanced. Even shifting attention in a pattern consistent with a problem’s solution may help insight.

40

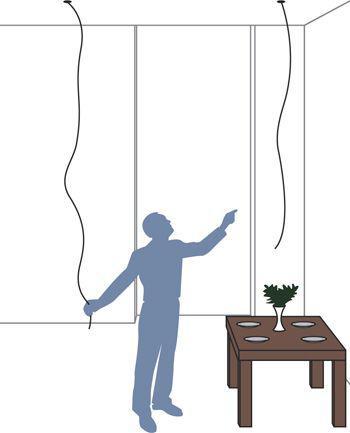

For example, an experimental task that is sometimes used is called the two string problem (see

Figure 4.4

).

38

Figure 4.4. The two-string problem

The task goal is to hold onto one string hanging from the ceiling and then grab another string too far away to be reached that is above a table with objects on it. The solution involves tying a weight to the other string and then swinging it so that the string can be grasped. If you ask subjects (who do not know the connection between movement and solutions) to swing their arms versus stretch their arms while thinking of a solution to the problem, subjects who practice swinging their arms will be more likely to solve the problem than those who practice stretching. Thus, the aligned movement provides a mental solution. Action centers in the brain, when activated, can stimulate thought.

The Neuroscience of the “Impostor Syndrome”

In an article in the

Harvard Business Review

, the author Manfred F.R. Kets de Vries describes “the dangers of feeling like a fake....”

41

Usually, this impostor syndrome is characterized by fear of failure, fear of success, perfectionism, procrastination, and workaholism. de Vries describes how high achievers can damage their own careers and in the process, bring down the organization as well. Their anxiety triggers behavior that serves their fears rather than their talents.

In part, this arises because talented people experience “gaps” in their awareness of their success. Because leaps of success often involve unconscious processes, an accumulation of unconscious processes can lead to these talented individuals seeking justifications for their success while they believe that something is unbelievable about this. Part of the reason it is unbelievable is that it is not easily remembered because conscious thought and action have only played a partial role in it. Therefore, there are no conscious memories of their success.

Also, when people acquire higher-level skills to become leaders, they often lose their more technical knowledge. They may be able to direct followers (managers or employees) to the correct material but since they learned the material a long time ago, they may have forgotten it. Their conceptual memory is enhanced but their technical memory is reduced.

The amygdala probably activates to the anxiety of not remembering and disrupts thinking and planning processes, thereby undermining future planning and goal orientation.

A recent article explains that when we do the very opposite of what we are capable of, it is because the unconscious monitoring system of the brain has become so loud that it turns off our conscious brains.

42

As a result, our brains become “primed” by negative ideas. They only hear fears of the opposite of what we are trying to do. Stress, in particular, switches conscious brain systems off. When leaders become afraid of

making mistakes, they put themselves under stress. This stress results in them falling into the prudence trap. Being overly prudent disrupts the flow of thinking, because this prudence is a manifestation of anxiety that disrupts thinking. The brain also goes into “hypervigilance mode,” and at a certain level of stress, this turns off the conscious brain and leaves the unconscious brain on. But the unconscious brain responds to priming with phrases that carry high significance and does not hear “do not” when the prudent leader tries to prevent mistakes. As a result, when the leader thinks, “Do not fumble at the meeting,” the unconscious brain under stress hears “fumble” and the brain obeys this instruction.

The application:

Preventing the impostor syndrome is better than waiting for it to occur. To address this, coaches must explain to leaders that their success has a shadow side—the side of self-questioning. Lack of answers for success may mean that much of the “important stuff” was unconscious. Coaches can encourage leaders to trust letting go, as they have previously, and then work with them to do this.

Leaders who suddenly become too conscious may disrupt their own flow. It is like a figure skater who suddenly questions his or her flow on the ice and starts to stumble, or a musician who loses the spontaneity and starts to play mechanically. Leaders need to be embraced from time to time in protective ways so that they can flow the way they used to—that is, so that they can allow the unconscious brain to do its thing.

Chapter 8

describes methods to apply to specific brain regions.

The Neuroscience of Mirrored Self-Misidentification

When people look at themselves in a mirror and cannot see who that person is, the challenge of dealing with this syndrome is difficult. Leaders are notorious for this syndrome because the history of successes provokes narcissistic crises. At the core of not being able to see themselves is a fear of people recognizing that they are different. In this way, leaders may still want to be seen as representing core social values when they don’t.

Research has shown that lesions of the right hemisphere can alter a sense of self-knowing.

43

Other case histories have shown that mirrored self-misidentification (not recognizing the self upon reflection) may also be due to right hemisphere dysfunction.

44

This seeming disorientation to self can be seen especially in leaders who have been absorbed in a complex problem and have been wrapped up in finding a solution. If this is the constant mode of operation of the leader, coming out may feel very disorienting.

The application:

When leaders lack self-awareness, admiration from others does not sustain a positive response to the self. This is because the deficit is not in being recognized as being great by others, but in not recognizing the self. This is a critical point, and I have come across this in many leaders.

Martin B. was the CEO of a prominent company. The company had been doing poorly when he was hired, but within five years it was back on track again. The effort that it took Martin to turn around the company was the greatest achievement of his career. Everyone admired him, and he was pleased with the results, but deep within him the victory sensation lasted for a minute and was then gone. No matter how much people told him how great he was, he became progressively depressed because this did not match with how he felt. If anything, it made him anxious and less productive, and his performance started to decline. Here, we have a case of summit syndrome (discussed next) as well as right hemisphere dysfunction in not recognizing oneself.

Thus, pointing to strengths to augment the egos of leaders is a short-lived success, and once the coach is gone, there is no guarantee that this perception will last. Instead, empowering the leader with the tools for self-perception is critical, but the crucial thing to recognize is that you are working with a brain that does not know how to automatically do this. We will examine specific interventions later.