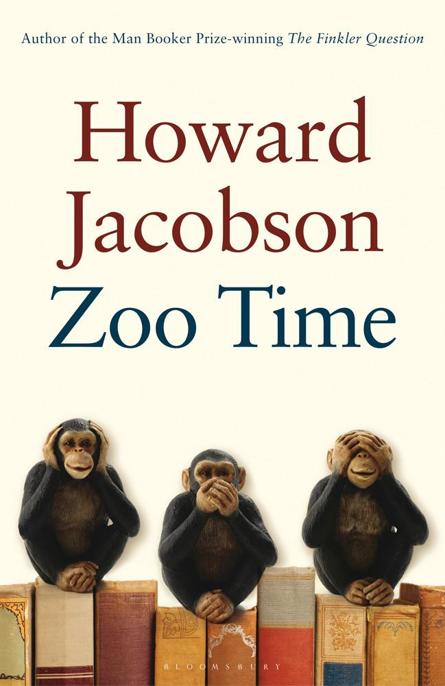

Zoo Time

Authors: Howard Jacobson

To

Jenny and Dena

and

Marly and Nita

‘Will any man love the daughter if he has not loved the mother?’

James Joyce,

Ulysses

Contents

8 So What Are We Going To Do With You?

10 Are There Monkeys in Monkey Mia?

16 All the World Loves a Wedding

28 How Much Did Your Last Book Make?

31 Every Living Writer is Shit

33 Read Me, Read Me, Fuck Me, Fuck Me

35 Too Late for the Apocalypse

Also available by Howard Jacobson

ONE

1

When the police apprehended me I was still carrying the book I’d stolen from the Oxfam bookshop in Chipping Norton, a pretty Cotswold town where I’d been addressing a reading group. I’d received a hostile reception from the dozen or so of the members who, I realised too late, had invited me only in order to be insulting.

‘Why do you hate women so much?’ one of them had wanted to know.

‘Could you give me an example of my hatred of women?’ I enquired politely.

She certainly could. She had hundreds of passages marked with small, sticky, phosphorescent arrows, all pointing accusingly at the pronoun ‘he’.

‘What’s wrong with “he stroke she”?’ she challenged me, making the sign of the oblique with her finger only inches from my face, wounding me with punctuation.

‘ “He” is neuter,’ I told her, stepping back. ‘It signifies no preference for either gender.’

‘Neither does “they”.’

‘No, but “they” is plural.’

‘So why are you against plurality?’

‘And children,’ another had wanted to know, ‘why do you detest children?’

I explained that I didn’t write about children.

‘Precisely!’ was her jubilant reply.

‘The only character I identified with in your book,’ a third reader told me, ‘was the one who died.’

Only she didn’t say ‘book’. Almost no one any longer said ‘book’, to rhyme with took or look, or even fook, as in ‘Fook yoo, yoo bastad’, which was the way it was pronounced in flat-vowelled lawless Lancashire just a few miles to the north of the sedate, sleepy peat bogs of Cheshire where I grew up. Berk, was how she said it. ‘The only character I identified with in your

berk

. . .’ As though a double ‘o’ was a hyperbole too far for her.

‘I’m gratified you found her death moving,’ I said.

She was quivering with that rage you encounter only among readers. Was it because reading as a civilised activity was over that the last people doing it were reduced to such fury with every page they turned? Was this the final paroxysm before expiry?

‘Moved?’ I feared she might strike me with my berk. ‘Who said I was moved? I was envious. I identified with her because I’d been wishing I was dead from the first word.’

‘

Were

dead,’ I said, putting on my jacket. ‘I’d been wishing I

were

dead.’

I thanked them for having me, went back to my hotel, polished off a couple of bottles of wine I’d had the foresight to buy earlier, and fell asleep in my clothes. I’d agreed to go to Chipping Norton for the opportunity it afforded me to visit my mother-in-law with whom I had for a long time been thinking of having an affair, but the stratagem had been foiled by my wife uncannily choosing that very time to have her mother visit us in London. I could have caught the train back and joined them for dinner, but decided to have a day to myself in the country. It wasn’t only the women at the reading group who wished they was dead.

Getting up too late for breakfast, I took a stroll through the town. Nice. Cotswold stone, smell of cows. (‘Why are there no natural descriptions in your novels?’ I’d been unfairly interrogated the day before.) Needing sustenance, I bought a herby sausage roll from an organic bakery and wandered into the Oxfam bookshop eating it. A chalk-white assistant with discs in his earlobes, like a Zambezi bushman, pointed to a sign saying ‘No food allowed on the premises’. A tact thing, presumably: you don’t fill your face when the rest of the world is starving. From his demeanour I assumed he knew I was a hater of Zambezi bushmen as well as women and children. I put what was left of the sausage roll in my pocket. He was not satisfied with that. A sausage roll in my pocket was still, strictly speaking, food on the premises. I stuffed it slowly into my mouth. We stood, eyeing each other up – white Zambezi bushman and Cheshire-born, London-based misogynistic, paedophobic writer of berks, buhks, boks, anything but books – waiting for the sausage roll to go down. Anyone watching would have taken the scene to be charged with post-colonial implications. After one last swallow, I asked if it was all right now for me to check out the literary-fiction section.

Literary

. I burdened the word with heavy irony. He turned his back on me and walked to the other end of the shop.

What I did then, as I explained to the constables who collared me on New Street, just a stone’s throw from the Oxfam bookshop, I had to do. As for calling it stealing, I didn’t think the word was accurate given that I was the author of the book I was supposed to have stolen.

‘What word would you use, sir?’ the younger of the two policemen asked me.

I wanted to say that this more closely approximated to a critical discussion than anything that had taken place in the reading group, but settled for answering his question directly. I had enough enemies in Chipping Norton.

‘Release,’ I said. ‘I would say that I have

released

my book.’

‘Released it from what exactly, sir?’ This time it was the older of the two policemen who addressed me. He had one of those granite bellies you see on riot police or Louisiana sheriffs. I wondered why they needed riot police or a Louisiana sheriff in Chipping Norton.

Roughly, what I said to him was this:

Look: I bear Oxfam no grudge. I would have done the same in the highly unlikely event of my finding a book of mine for sale second-hand in Morrisons. It’s a principle thing. It makes no appreciable difference to my income where I turn up torn and dog-eared. But there has to be a solidarity of the fallen. The book as prestigious object and source of wisdom – ‘Everyman, I will go with thee and be thy guide’ and all that – is dying. Resuscitation is probably futile, but the last rites can at least be given with dignity. It matters where and with whom we end our days. Officer.

Before they decided it was safe, or at least less tedious, to return me to society, they flicked – I thought sardonically, but beggars can’t be choosers – through the pages of my book. It’s a strange experience having your work speed-read by the police in the middle of a bustling Cotswold town, shoppers and ice-cream-licking tourists stopping to see what crime has been committed. I hoped that something would catch one of the cops’ eye and make him laugh or, better still, cry. But it was the title that interested them most.

Who Gives a Monkey’s?

The younger officer had never heard the expression before. ‘It’s short for who gives a monkey’s fook,’ I told him. I had lost much and was losing more with every hour but at least I hadn’t lost the northerner’s full-blooded pronunciation of the ruderies, even if Cheshire wasn’t quite Lancashire.

‘Now then,’ he said.

But he had a question for me since I said I was a writer –

since I said I was a writer

: he made it sound like a claim he would look into when he got back to the station – and as I obviously knew something about monkeys. How likely did I think it was that a monkey with enough time and a good computer could eventually write

Hamlet

?

‘I think you can’t make a work of art without the intentionality to do so,’ I told him. ‘No matter how much time you’ve got.’

He scratched his face. ‘Is that a yes or a no?’

‘Well, in the end,’ I said, ‘I guess it depends on the monkey. Find one with the moral courage, intelligence, imagination and ear of Shakespeare, and who knows. But then if there were such a monkey why would he want to write something that’s already been written?’

I didn’t add that for me the more interesting question was whether enough monkeys with enough time could eventually ‘read’

Hamlet

. But then I was an embittered writer who had just taken a battering.

The Louisiana sheriff, meanwhile, was turning the evidence over in his hands as though he were a rare-book dealer considering an offer. He opened

Who Gives a Monkey’s?

at the dedication page.