100 Cats Who Changed Civilization (11 page)

PETER

THE CAT WHO DROVE

HIS MASTER NUTS

One of the most famous illustrators of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was an Englishman named Louis Wain. He made his fortune drawing fanciful pictures of anthropomorphized cats doing everything from playing golf to having tea. This feline version of the dogs-playing-poker franchise was inspired by Wain’s own pet, Peter.

Sadly, Wain’s cat pictures provide a riveting visual record of his eventual descent into madness. Born August 5, 1860, Wain began his artistic career as a teen. During his early twenties he worked as a freelancer of modest reputation. Then his wife, Emily, began a long struggle with cancer, which would eventually claim her life. Since she took great solace from their black and white cat, Peter, Wain taught him tricks, such as wearing spectacles. Then he started drawing the cat in more fanciful situations, and a new career was born. “To him properly belongs the foundation of my career, the developments of my initial efforts, and the establishing of my work,” he wrote.

For years thereafter, Peter would be seen again and again in his master’s renderings. In 1886, Wain drew a massive piece called

A Kitten’s Christmas Party

for the

Illustrated London News

. It won

him wide acclaim, and soon his pictures of upright-walking, clothes-wearing cats were everywhere. It’s hard to overestimate Wain’s popularity. His felines graced everything from greeting cards to children’s books to the

Louis Wain Annual

, a magazine devoted to his caricatures. He was to cats what Thomas Kinkade is to cottages.

Sadly, though the artist’s work is still remembered today, it is for a darker reason. Late in life Wain developed schizophrenia and spent almost two decades confined to mental hospitals before his death in 1939. He painted until the end, unwittingly creating a disturbing record of his descent into madness. As his schizophrenia took hold, the clothes-wearing cats disappeared. Instead Wain created ever more abstract-looking feline portraits, with the subjects rendered in bright, almost psychedelic colors and sporting surprised, even terrified, expressions. In his final works—basically collections of small, geometric shapes—the “cats” are merely complex kaleidoscopic patterns. And yet, even toward the end, the poor mad artist occasionally created portraits that looked like Peter, the cat who started it all.

MASTER’S CAT

THE CAT WHO CHARMED

THE DICKENS OUT OF DICKENS

English novelist Charles Dickens was a great fan of dogs and birds—so fond, in fact, that for years cats were banned from his London household, lest they make off with his feathered friends. But all that changed when Dickens’s daughter, Mamie, received a white kitten as a gift. The cat was christened William. Shortly thereafter, after giving birth to kittens, she was rechristened Williamina.

The feline family was supposed to stay in a box in the kitchen. But Williamina had other plans. One by one she carried her kittens into Dickens’s study and deposited them in a corner. Dickens told his daughter that they couldn’t stay and had her take them back to the kitchen. But Williamina brought them back. Mamie removed them again, only to have the mother once more laboriously haul them into the study. Only this time she laid them directly at the great man’s feet and then stared at him imploringly, as if begging permission to stay.

It was finally granted, and the kittens enjoyed the privilege of climbing up the curtains and scampering across Dickens’s desk as he tried to work. When they were old enough, all were found good homes—except for a single deaf kitten.

Because it could never hear its name, it was never given one. Instead he was known simply as “the master’s cat.” And indeed he was. He followed Dickens like a dog throughout the house and would sit by him at his desk as he wrote.

Not that the master’s cat didn’t demand a certain level of attention from the master. One night, when the rest of his family went out to attend a ball, Dickens sat in his study by a candle, engrossed in a book. The cat, as usual, was at his side. Suddenly the candle flickered out. Dickens, too engrossed in his reading to notice the cause, relit the candle and continued. He also gave a passing pat on the head to his cat, who stared at him longingly.

A minute or two later, the candle flickered again. Dickens looked up just in time to see his companion deliberately trying to put out the flame with his paw. The author set his book aside and played with the cat, then shared the story with his family the next day.

HAMLET

THE CAT WHO HELD COURT OVER

A LITERARY ROUND TABLE

For decades, Manhattan’s elegant Algonquin Hotel has been a gathering place for the city’s theater crowd and literati. But during its heyday, its greatest celebrity arguably wasn’t Dorothy Parker or Robert Benchley but a scraggly former stray cat named Hamlet.

According to legend, the feline, originally called Rusty, was an unemployed theater cat taken in by the hotel’s owner, Frank Case. It must have been quite a step up. The old tomcat was renamed Hamlet and given the run of the hotel. He even got his own cat door to ease his travels and is said to have enjoyed lapping milk from a champagne glass. When he passed away after only three years on the job, the

New York Times

noted his departure in its gossip column.

Though the original Hamlet is a distant memory, the tradition of keeping a cat at the Algonquin lives on. Today the position is held by a former animal shelter inmate named Matilda. Like her predecessors, she has the run of the place (save for the kitchen and hotel dining room) and receives fan mail from around the world.

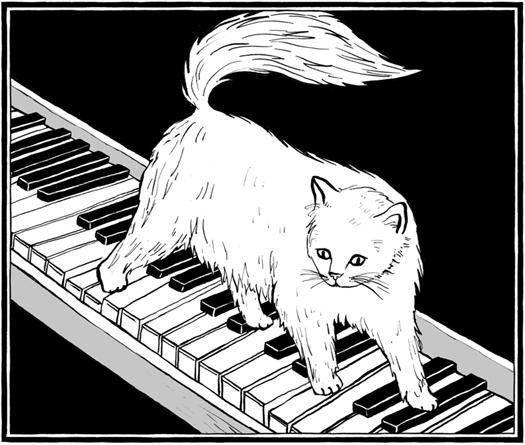

PULCINELLA

THE CAT WHO WROTE A FUGUE

Today the name Domenico Scarlatti doesn’t exactly fall trippingly off the tongues of music aficionados. In the early eighteenth century, however, the Italian-born composer was famous throughout Europe. A master of the keyboard, he commanded respect both from his contemporaries and successors. He was considered George Frederic Handel’s equal on the harpsichord. Artists ranging from Chopin to Brahms to Vladimir Horowitz have idolized his work for centuries, but he was also extremely popular with lay audiences.

He was as prolific as he was skilled. During his lifetime (1685–1757) he created several operas and produced some five hundred sonatas, all while holding various high-profile musical posts in Italy, England, Portugal, and Spain, where he lived for more than two decades. Scarlatti became famous not just for his intricate, innovative keyboard pieces, but also for his somewhat unorthodox style, which sampled everything from religious themes to Spanish, Moorish, and Jewish folk music. But one of his most famous pieces was inspired not by some rustic melody or the work of another composer. It was a collaboration with his cat. Officially called the Fugue in G minor, Kk. 30, this one-movement

harpsichord sonata is unofficially known as the Cat’s Fugue.

According to legend, the maestro owned a cat named Pulcinella, who enjoyed walking up and down the keyboard of his harpsichord. Usually this produced only random, meaningless noise. But during one of these “improvisation sessions,” the feline plinked out an unusual, though quite catchy, series of notes. Scarlatti grabbed a pad and wrote down the short phrase. Inspired, he composed an entire fugue around it.

The piece became an instant success, and it remains so today. During the 1840s, the great pianist Franz Liszt added the work to his

repertoire—it became a regular part of his performances. By that time a major oversight on Scarlatti’s part had been rectified. At the time he wrote it, the idea of somehow noting the origin of the piece in the title simply didn’t occur to him. But by the early nineteenth century the brilliant bit of feline-inspired music had become universally known as the Cat’s Fugue.

CALVIN

THE CAT WHO INSPIRED

TWO AUTHORS

It is the rarest of literary cats who serves as the muse of not one but two writers. Such was the case for a fluffy Maltese named Calvin. He entered the world of letters in the mid-nineteenth century, when he wandered “out of the great unknown” into the household of Harriet Beecher Stowe. “It was as if he had inquired at the door if this was the residence of the author of

Uncle Tom’s Cabin

, and, upon being assured that it was, had decided to dwell there,” remarked family friend Charles Dudley Warner. Calvin immediately made himself at home. He hovered nearby as Stowe wrote, sometimes even perching on her shoulders. All were impressed not only by the feline’s self-confidence, but by his intelligence. “He is a reasonable cat and understands pretty much everything except binomial theorem,” said Warner.