100 Most Infamous Criminals (15 page)

Read 100 Most Infamous Criminals Online

Authors: Jo Durden Smith

On the morning of August 28th 1962, the de Kaplanys’ neighbours heard the sound of screams buried beneath the vast noise of a stereo blasting out from the de Kaplanys’ apartment. They hammered on the walls, doors and windows to no effect. Then they called the police. When the police arrived, they too banged on the front door. Suddenly the music stopped, and the door opened, to reveal Geza de Kaplany sweating and grinning like a crazy man, dressed only in underwear and wearing rubber gloves on his hands. He said he had to go back to work, and the police followed him in.

In the bedroom, they found Hajna de Kaplany naked, spreadeagled on the bed and tied at wrists and ankles to the bedposts. She’d been appallingly disfigured and mutilated. There were bottles of nitric, sulphuric and hydrochloric acid on the bedside bureau. Her face had been obliterated; and her breasts and genitals had been savagely slashed. When the ambulance arrived, the paramedics burned their hands wherever they touched her body. For de Karpany had made small incisions all over his wife and had then seen which acid caused the most pain. He’d been at it for several days.

As her mother sat beside Hajna’s bed in the intensive care unit, praying that she would not die, her son-in-law calmly told the police that he’d been extremely methodical. He’d bought the stereo and installed several speakers. He’d also had a manicure so that he wouldn’t puncture the rubber gloves while handling the acids he brought from the hospital. Then while Hajna slept, he’d pinioned her, stripped her and tied her up. After the stereo had been turned up full blast, he’d held up a piece of paper in front of her on which he’d written the words:

‘If you want to live – do not shout; do what I tell you or else you will die.’

She did die – after thirty-three days of agony; and Geza de Kaplany was charged with her murder. At his trial, he said he hadn’t intended to kill her, just to make her less attractive. But when he was shown pictures of her brutalized body, he went berserk, shouting:

‘I am a doctor! I loved her! If I did this – and I must have done this – then I am guilty!’

He was given life imprisonment, but for reasons that have never been clear, he was classified as a ‘special interest prisoner,’ and was released, well before his first official parole date, in 1975. The reason that was given at the time was that he was urgently needed ‘as a cardiac specialist’ at a Taiwan missionary hospital. De Kaplany was not a cardiac specialist. But nevertheless he was in effect smuggled out of the country in one of the most flagrant abuses of the parole system in California ever seen. He relocated to Munich and remarried. Over the course of more than twenty years, he became a naturalized German citizen, thereby precluding the possibility of extradition for the parole violation.

Albert DeSalvo

A

lbert DeSalvo was oversexed, everyone agreed. His lawyer, F. Lee Bailey, wrote that he was,

‘without doubt, the victim of one of the most crushing sexual drives that psychiatric science has ever encountered.’

His wife said he demanded sex up to a dozen times a day; and a psychiatrist from his army days in Germany explained why she complained:

‘He made excessive demands on her… she did not want to submit to his kind of kissing which was extensive as far as the body was concerned.’

If it hadn’t been for this monumental sexual appetite of his, everything might have gone well for Boston handyman DeSalvo. For he was, to all appearances, a clean-living individual. He neither smoked nor drank. He was a sportsman – he’d been middleweight boxing champion of the US Army. His hair was always neatly swept back and he prided himself on his freshly laundered white shirts. But the need for sex kept getting him into trouble. In Germany, it was the officers’ wives; at Fort Dix, it was a nine-year-old girl he was alleged to have molested. And in Boston, after he’d been honourably discharged and had moved back to his native state, it was all the gullible pretty women who wanted to be models.

In 1958, Albert DeSalvo began to be known in police circles as the ‘Measuring Man’. An unknown man, posing as a talent scout for a modelling agency, had started smooth-talking his way into women’s apartments and cajoling them into having their measurements taken. He wouldn’t attack them, but he would touch, even caress them, whenever and wherever he could. Then he’d leave, saying that a senior executive of the agency would soon be in touch. When this didn’t happen, some of the women complained – but not all, said De Salvo later. Many of them were willing to pre-pay, with sex, for their future careers.

He was finally caught in March 1960, when he was arrested, almost by accident, as a suspected burglar. Even though he soon confessed, the police took it for granted that the ‘Measuring Man’ act was simply a device for entering apartments and houses he intended later to rob. In fact, he was only convicted – and duly recorded – as a ‘breaker and enterer’: a fact that the police, indeed the entire population of Boston, were later to regret.

When he got out of prison, after serving an 11-month term, DeSalvo’s wife, as her own form of punishment, denied him all sexual contact. So DeSalvo was forced to take on a new identity, this time that of the ‘Green Man’. The ‘Green Man’ got his name from the green trousers he liked to wear when talking his way or breaking into women’s houses; and he was both a more dangerous and a wider-ranging character. In other northeastern states as well as Massachusetts, he’d strip some of his victims at knifepoint and then kiss them all over; others he would tie up and rape. Many of them, he later claimed, hadn’t complained at all and had heartily joined in. He boasted of having ‘had’ six women in a single morning.

Alberto DeSalvo became known as the ‘Measuring Man’

In 1962, though, another and yet more sinister character appeared on the scene, one that was to terrorize Boston for eighteen months: The Boston Strangler. In June of that year, the naked body of a middle-aged woman was found in her apartment, clubbed, raped and strangled. Her legs had been spreadeagled and the cord from her housecoat had been wound round her neck, then tied beneath her chin in a bow. The necktie, the bow and the spreadeagling were all to become, as the months dragged on, horrifyingly familiar.

Two weeks later, the Strangler struck twice. Both victims were women in their sixties. Two more were murdered, a day apart, in August 1962, one 75, one 67. Then, in December, he struck once more – and from then on no woman in Boston felt safe, for she was only 21. Sophie Clark was strangled and raped, and her body, when it was found, carried all the marks of the Strangler.

The killings went on, with increasing violence, until January 1964. There was no particular pattern, apart from the spreadeagling, the bow, the ligature. The youngest victim was 19, the oldest 69. As the number of dead mounted up, panic increasingly gripped the city. Few – except for patrol cops – chose to walk the streets at night. When husbands had to leave the city, wives kept guns at their bedsides. The police were inundated with calls and condemned in the press. But Albert DeSalvo was never even interviewed.

Then, though, the killings stopped. After January 1964 the Strangler seemed to disappear – even though the ‘Green Man’ was still at work. For that autumn a young married student called the Cambridge police to say that she’d been tied up and sexually assaulted by an intruder. The description she gave tallied with that of the ‘Measuring Man’, and DeSalvo was arrested. Meanwhile police in Connecticut, who’d been investigating similar attacks during the summer of ’64 in their state, finally identified him as the ‘Green Man’. DeSalvo was held on $100,000 bail and sent to Bridgewater mental hospital for routine observation. He was later sent back there by a judge when declared

‘potentially suicidal and… schizophrenic.’

It was at Bridgewater that the controversy that still surrounds DeSalvo’s name began. For a prisoner called George Nassar, who’d been arrested for murder, was in the same ward as DeSalvo and realized, from his boasts, so he said, that he had to be the Boston Strangler. He told his lawyer, F. Lee Bailey, and Bailey himself spoke to DeSalvo and taped his confession – not only to the Strangler’s known murders, but also to two others.

In a complicated deal engineered by Bailey, DeSalvo in the end stood trial only for the ‘Green Man’ offences. He was sentenced to life imprisonment; and is said to have confessed in detail to the Boston Strangler’s crimes at a special meeting of doctors and law enforcement officers in 1965. Even so there remain some doubts. For the ‘Measuring Man’ and the ‘Green Man’ invariably chose younger women than the Boston Strangler. Witnesses who’d actually seen the Strangler failed to identify him. So could the Boston Strangler have really been George Nassar, who’d somehow fed DeSalvo details of the crimes in Bridgewater and then persuaded him to confess? Could there in fact have been several killers? We shall never know. For DeSalvo was stabbed to death in Walpole State Prison in 1975. The inmate who knifed him through the heart was never identified.

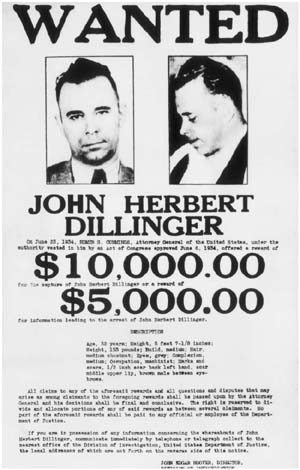

John Dillinger

T

here was something desperate, death-or-glory, about John Dillinger. For his big-time career as America’s most wanted criminal lasted, in fact, little more than a year. He came out of prison in May 1933 after a nine-year stretch, and by July the following year he was dead, gunned down outside a cinema in Chicago. In that short space of time he robbed untold numbers of banks, broke into police armouries, escaped from prison twice, and survived at least six different shoot-outs. If he hadn’t existed, J. Edgar Hoover’s Bureau of Investigation – which made its reputation out of his identification and death – would have had to invent him.

John Herbert Dillinger was born into a religious Indianapolis Quaker family in 1902, and moved with it to Mooresville, Indiana eighteen years later. In 1923, after an unhappy love-affair, he joined the navy. But he deserted soon after, married a local girl and then, in September 1924, was sent down for nine years for assault while attempting to rob a grocer. He seems to have come out of prison nine years later as a man with a mission. For within a month, he’d robbed an Illinois factory official and within two, he’d committed his first bank robbery. At this point he gathered a gang together, among them ‘Baby Face Nelson’ Gillis, and together they went on a spree, robbing banks all over the Midwestern states and killing anyone who stood in their way.

Dillinger became the FBI’s Public Enemy No1

There were occasional hiccups. In July 1933, Dillinger was arrested for his part in a Bluffton, Ohio bank heist. But three of the gang posed as prison officials and soon got him out – the spree went on. They moved from rural banks to the big city: they robbed the First National Bank in East Chicago, and escaped with $20,000, killing a policeman on the way. And though Dillinger was again arrested – this time in Tucson, Arizona for possession of stolen banknotes and guns – this did little to cramp his style: legend has it that he carved himself a wooden gun, held up officials with it and bluffed his way out the joint.

The only other thing he did wrong on this occasion was to steal a car from a sheriff and drive it across the state line. But this was enough to involve J. Edgar Hoover’s Feds, who then played him up to the newspapers as a deranged killer even as they tried to track him down. Dillinger, in fact, had a reputation as a courteous man, particularly to women and children. So he resented the publicity, and did his best to avoid it. He tried to disguise himself via facial surgery – and he even had his finger ends shaved off to avoid identification.

In April 1934, a tip-off led the government men – or G-men, as George ‘Machine Gun’ Kelly seems to have been the first to call them – to a hide-out at a lodge in Little Bohemia, Wisconsin. The Feds, though, shot at the wrong car during a night-time raid, and Dillinger escaped, leaving a dead G-man behind him. Gradually, however, the net closed in. Rewards for information leading to Dillinger’s arrest were by now on offer from several states, and there’d even been a special appropriation voted by Congress to add to the pot.