100 Most Infamous Criminals (28 page)

Read 100 Most Infamous Criminals Online

Authors: Jo Durden Smith

Christie with his wife, who was later found buried under the floorboards

Four years later, though, in March 1953, a man named Beresford Brown, who had sublet John Christie’s apartment from him a few days before, found by accident a kitchencupboard door that had been papered over. He opened it and saw the naked back of a partly-mummified woman. He called the police, who quickly found two other women, hidden behind the first, carefully stuffed into the cupboard upright. There was another body, which turned out to be that of Christie’s wife, buried beneath the dining-room floor. Two more female skeletons were later found in the garden, as well as a human femur propping up a fence.

The four women in the house – three young prostitutes and Christie’s wife – had all been killed well after Evans’s execution. So a warrant was immediately put out for Christie’s arrest; he was recognized and taken in a week later as he stood quietly on Putney Bridge. He was confused and exhausted. But he quickly confessed to the murder of all six women, and later to that of Beryl Evans, though not that of her baby daughter.

When arrested, Christie confessed to the murder of six women

Little by little it emerged that Christie, who had been beaten as a child and then mocked by girls in his teens, was largely impotent with living women. So beginning in 1943, he started killing them, inviting them to the house when his wife was away, and then gassing and strangling them before having sex with their corpses. In December 1952 he finally disposed of his wife as an inconvenience; he was then free to kill when he chose. His last three victims died over a period of a few days.

Did Christie kill Beryl Evans? And if so, why did Timothy Evans say he himself had killed her when he gave himself up in Wales? The answer is that Beryl had been pregnant and Evans had told Christie that they wanted an abortion. Christie had offered to do it himself while Evans was at work. Then he persuaded Evans that Beryl had died during the operation and that if he didn’t make a run for it, he, Evans, would be held responsible. He offered to have the Evans’ daughter adopted by friends.

Before he was tried, Evans, who was mentally subnormal, had withdrawn his confession and had told this version of events to police, but he hadn’t been believed. And after Christie was hanged on July 15th 1953, a campaign began to have the young truck-driver posthumously pardoned. Finally, thirteen years later, a full enquiry was set up, headed by a High Court judge, who announced that, though Evans had probably murdered his wife, he had probably not murdered his daughter, the case for which he’d actually been tried. He was given his pardon. But though 10 Rillington Place, along with the rest of the street, has long since been torn down, a strong sense of injustice done lingers…

Dr. Hawley Harvey Crippen

D

r. Hawley Harvey, later Peter, Crippen is one of the most famous – and most reviled – murderers of the 20th century. Yet he was a small, slight man, intelligent, dignified, eternally polite and anxious for the welfare of those around him. With his gold-rimmed spectacles, sandy whiskers and shy expression, he was, in fact, more mouse than monster. His problem was his wife.

Crippen was born in Coldwater, Michigan in 1862, and studied for medical degrees in Cleveland, London and New York. Around 1890, his first wife died, leaving him a widower; three years later, when working in a practice in Brooklyn, he fell in love with one of his patients, a 17-year-old with ambitions to be an opera singer, called Cora Turner. She was overweight; her real name was Kunigunde Mackamotzki – she was the boisterous, loose daughter of a Russian-Polish immigrant. But none of this mattered to Crippen. He first paid for her singing lessons, and then he married her.

In 1900, by now consultant physician to a mail-order medicine company, Crippen was transferred to London to become manager of the firm’s head office and Cora came to join him. On arrival in London, though, she decided to change her name once again – this time to Belle Elmore – and to try out her voice in the city’s music halls. She soon became a success and acquired many friends and admirers. She bleached her hair; became a leading light in the Music Hall Ladies Guild; and entertained the first of what were to be many lovers. Increasingly contemptuous of her husband, whom she regarded as an embarrassment, she forced him first to move to a grand house in north London that he could ill afford, and then to act as a general dogsbody to the ‘lodgers’ she soon moved in.

Dr. Crippen is one of the most reviled murderers of the 20th century

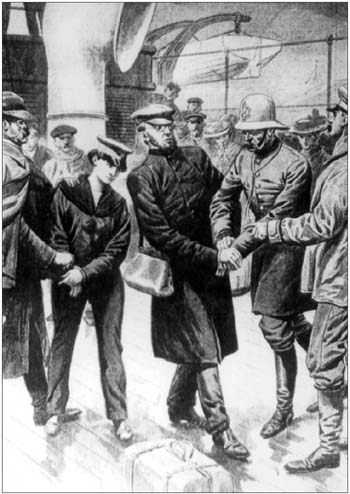

An artist’s impression of Crippen’s capture

Crippen took such consolation as he could with a shy secretary at his company called Ethel Le Neve. But in 1909, he lost his job, and his wife threatened to leave him, taking their life savings with her. By the beginning of the following year, he’d had enough. On January 19th, he acquired five grains of a powerful narcotic called hyoscine from a chemist’s in New Oxford Street; and the last time his wife was seen was twelve days later, at a dinner for two retired music-hall friends at the Crippens’ home. Two days after that, as it turned out, Crippen began pawning her jewellery, and sent a letter to the Music Hall Ladies Guild, saying that she’d had to leave for America, where a relative was seriously ill. Later he announced that she’d gone to the wilds of California; that she had contracted pneumonia; and, in March – after Ethel had moved into his house – that she had died there.

Two actors, though, who’d been touring in California returned to England and, when told, said they’d heard nothing at all about Cora’s death. Scotland Yard took an interest and Crippen was forced to concede that he’d made up the story: his wife had in fact left for America with one of her lovers. Though this seemed to satisfy the detectives, he then made his first big mistake: he panicked, settled his affairs overnight and left with Ethel the next day for Europe, after persuading her to start a new life with him in America. When the police called again, it was to find them gone. They began a thorough search of the house. What remained of his wife – rotting flesh, skin and hair – was found buried under the coal cellar.

Unaware of the furore of horror created by this discovery in the British press, Crippen – his moustache shaved off, under an assumed name, and accompanied by Ethel, disguised as his son – took a ship from Antwerp to Quebec in Canada. But they were soon recognized by the captain who, aware of a reward, used the new invention of the wireless telegraph to send a message to his employers. Each day from then on, in fact, he sent via the same medium daily reports on the doings of the couple which were published in the British newspapers. Meanwhile, Chief Inspector Dew of Scotland Yard took a faster ship and arrested Dr. Crippen and ‘son’ Ethel when they reached Canadian waters.

Huge, angry crowds greeted them when they arrived back a month later, under arrest, in England. The newspapers had done their job of transforming the pair of them into vicious killers. But Crippen always maintained that Ethel had had absolutely no knowledge of the murder, and when they were tried separately, she was acquitted. Crippen, though, was found guilty and was hanged in Pentonville Prison on November 23rd 1910. Before he died, he described Ethel as

‘my only comfort for the past three years. . . As I face eternity, I say that Ethel Le Neve has loved me as few women love men. . . Surely such love as hers for me will be rewarded.’

It is not known whether she was rewarded, or indeed what became of her, though one story recounts that she ran a tea-shop in Bournemouth, under an assumed name, for forty-five years…

Claude Duval

C

laude Duval’s epitaph called him ‘the Second Norman Conqueror’ and there’s no doubt at all that he was a 17th-century star. His biography was written by a professor of anatomy at Oxford University; he was the prototype for Macheath in John Gay’s hugely successful

The Beggar’s Opera

and his exploits were even noted approvingly by the famous historian Lord Macaulay. When he was finally caught in 1670, it’s said that large numbers of rich and fashionable women tried to intercede on his behalf. Perhaps taking offence, King Charles II said no. So the ladies had to make do instead with veiled visits to see his hanged body as it lay in state for several days in London’s Covent Garden.

Duval – whose biographer says was a cardsharp and confidence-trickster as well as a highwayman – was born in Normandy in 1643, but gravitated to Paris, where he fell in with Royalist exiles waiting for the death of Oliver Cromwell and the restoration of the British monarchy. At the age of 17, then, he crossed the Channel to London as a footman to the Duke of Richmond. But he didn’t stay in service long. For the days of Puritan austerity were finally over: with the King setting an example, the gentry were dressing up in finery again, and taking to the roads to visit each other or to travel to their estates. It was an opportunity too good to miss.

Duval, then became a holdup-man – but a holdup-man with a difference. For he was well-dressed, courteous and good-looking and it wasn’t long before women travellers were having daydreams about being waylaid by him. On one occasion, he’s said to have played the flute and danced with one of his pretty victims – giving up £300, a vast sum, for the privilege. On another, he gravely handed back a solid-silver bottle to a woman traveller who was feeding her baby with it.

As his legend grew, so did his standing in the most-wanted list published in the

London Gazette

and the reward offered for his capture. A road was named after him in Hampstead, near the site of one of his robberies. He became a byword for daring and glamour. Then, though, in January 1670, he was finally caught – and all too prosaically. He was recognized in a London pub run by an ex-mistress of the Duke of Buckingham called The Hole in the Wall (the name, much later, of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid’s retreat) and he was too drunk to put up much resistance.

Tried on six charges, he was soon condemned to death. But so popular had he become that at his hanging there were riots. His body was taken down by the crowd and carried to a tavern in St. Giles-in-the-Fields, where it lay, open to all-comers, for several days. Finally, after a long torchlit procession, Claude Duval was buried under the central aisle of St. Paul’s Church in Covent Garden. His epitaph began:

‘Here lies Du Vall: Reader, if male

thou art,

Look to thy purse; if female to thy

heart.’

Ruth Ellis

R

uth Ellis, born in Rhyl, Wales in 1927, has the distinction of being the last woman in Britain to be hanged. Twenty-eight years old when she went to the scaffold, she was as much victim as killer.

Men, from the beginning, were Ruth Ellis’s problem – and she theirs. Raised in Manchester – a waitress and for a while a dance-band singer – she’d fallen in love at the age of 17 with an American flyer, only for him to be killed in action in 1944. Soon after his death she bore him a son and six years later she married a dentist and had a baby daughter by him – only for him to divorce her shortly afterwards on the grounds of mental cruelty. Now with two small children to take care of, and with no qualifications except her looks, she did what she had to. She became a club-hostess and hooker. She migrated to London and there, in Carrolls Club in 1953, she met a man called David Blakely.