100 Most Infamous Criminals (2 page)

Read 100 Most Infamous Criminals Online

Authors: Jo Durden Smith

It was only with the famous raid at Entebbe airport – when Israeli commandos rescued the passengers of an El Al aircraft hijacked by Palestinian gunmen – that Amin was finally exposed as a international pariah, and his reign of terror came to an end. Even then, though, he had one more trick up his sleeve. In a last attempt to get the support of his countrymen, he announced that Tanzania was getting ready to invade, an invasion that he did his best to provoke by sending raiders across the border into Tanzanian territory. When the Tanzanians did finally respond by sending their army into Uganda, it was welcomed with open arms. Amin fled to Libya, and then subsequently to a private hotel suite in Riyadh in Saudi Arabia, courtesy of the Saudi royal family. He died, still in exile, in 2003.

Countess Elizabeth Bathory

W

hen Countess Elizabeth Bathory, aged 15, married Count Nadasdy in around 1576, it was an alliance between two of the greatest dynasties in Hungary. For Nadasdy, the master of Castle Csejthe in the Carpathians, came from a line of warriors, and Elizabeth’s family was even more distinguished: It had produced generals and governors, high princes and cardinals – her cousin was the country’s Prime Minister. Long after they’ve been forgotten, though, she will be remembered. For she was an alchemist, a bather in blood – and one of the models for Bram Stoker’s Dracula.

She was beautiful, voluptuous, savage – a fine match for her twenty-one-year-old husband, the so-called ‘Black Warrior’. But he was forever off campaigning, and she remained childless. More and more, then, she gave in to the constant cajolings of her old nurse, Ilona Joo, who was a black witch, a satanist. She began to surround herself with alchemists and sorcerers; and when she conceived – she eventually had four children – she may have been finally convinced of their efficacy. For when her husband died, when she was about 41, she surrendered to the black arts completely.

There had long been rumors around the castle of lesbian orgies, of the kidnappings of young peasant women, of flagellation, of torture. But one day after her husband’s death, Elizabeth Bathory slapped the face of a servant girl and drew blood; and she noticed that, where it had fallen on her hand, the skin seemed to grow smoother and more supple. She was soon convinced that bathing in and drinking the blood of young virgins would keep her young forever. Her entourage of witches and magicians – who were now calling for human sacrifice to make their magic work – agreed enthusiastically.

Elizabeth and her cronies, then, began scouring the countryside for children and young girls, who were either lured to the castle or kidnapped. They were then hung in chains in the dungeons, fattened and milked for their blood before being tortured to death and their bones used in alchemical experiments. The countess, it was said later, kept some of them alive to lick the blood from her body when she emerged from her baths, but had them, in turn, brutally killed if they either failed to arouse her or showed the slightest signs of displeasure.

Peasant girls, however, failed to stay the signs of ageing, and after five years Elizabeth decided to set up an academy for young noblewomen. Now she bathed in blue blood, the blood of her own class. But this time, inevitably, news of her depravities reached the royal court; and her cousin, the prime minister, was forced to investigate. A surprise raid on the castle found the Countess in midorgy; bodies lying strewn, drained of blood; and dozens of girls – some flayed and vein-milked, some fattened like Strasburg geese awaiting their turn – in the dungeons.

Countess Bathory pursued a grisly beauty regime

Elizabeth’s grisly entourage was taken into custody and then tortured to obtain confessions. At the subsequent trial for the murder of the eighty victims who were actually found dead at the castle, her old nurse, Ilona Joo, and one of the Countess’s procurers of young girls were sentenced to be burned at the stake after having their fingers torn out; many of the rest were beheaded. The Countess, who as an aristocrat could not be arrested or executed, was given a separate hearing in her absence at which she was accused of murdering more than 600 women and children. She was then bricked up in a tiny room in her castle, with holes left only for ventilation and the passing of food. Still relatively young and curiously youthful, she was never seen alive again. She is presumed to have died – since the food was from then on left uneaten – four years later, on August 21st 1614.

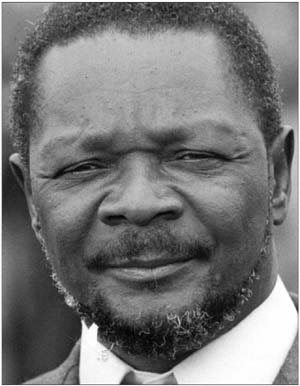

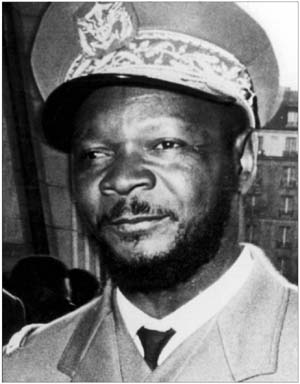

Jean Bedel Bokassa

T

o the French who’d once ruled the Central African Republic, Colonel Jean Bedel Bokassa must at first have seemed a good bet. For it was soon clear, after he seized power in 1966, that he longed to be more French than they. He worshipped De Gaulle and Napoleon and tried to set up in his capital of Bangui the sort of art, ballet and opera societies characteristic of a French provincial town. He made concessions to French companies; allowed the French army a base; and entertained French president Giscard D’Estaing several times on his own private game reserve, which occupied most of the eastern half of the country. He was also extremely generous with gifts – particularly of diamonds, one of the few commodities his dirt-poor country produced.

By 1977, though, even the French must have begun to suspect that this ugly, violent little man was beginning to lose touch with reality. For, spurred on by constant viewings of a film of the coronation of British Queen Elizabeth, he’d decided to emulate his hero Napoleon and have himself crowned Emperor. He’d even ordered a dozen prisoners held in Bangui Jail to be released from the general prison population and given exercise and proper rations in the run-up to the $20 million show.

French diplomats and businessmen, for all this, were among those who gratefully accepted invitations, and they were welcomed by brand-new Mercedes limousines paid for via a French government credit. They attended the comic-opera coronation and after the ceremonial parade – in which Bokassa rode in a gold carriage drawn by eight white horses over the only two miles of paved road in his capital – they assembled at his palace for a banquet, little knowing that among the delicacies served up to them on specially-ordered Limoges porcelain were what remained of the Bangui-Jail prisoners…

It still took the French two years to move against Bokassa, who by that time had run mad. He’d become obsessed, for example, by the fact that the barefoot children of Bangui’s only high school had no ‘civilized’ French-style uniforms. So he jailed them and then had them one by one beaten to death when they failed to show up at ‘uniform inspections’ properly dressed. When news of this reached the French Embassy, they were finally forced to act. As Bokassa was leaving his ‘Empire’ for a state visit to Libya, an opposition politician was shaken awake in Paris and bundled on a plane to Bangui, where he called upon the French Foreign Legion troops who were hard upon his heels to ‘aid the people’ in Bokassa’s overthrow.

The legionnaires soon uncovered the mass grave where the schoolchildren had been buried in the grounds of Bangui Jail. The bones of another thirty-seven were found at the bottom of the swimming pool in Bokassa’s palace – they’d been fed to his four pet crocodiles. In the palace kitchen were the half-eaten remains of another dozen victims who’d been on the Emperor’s menu in the days before his departure.

Jean Bedel Bokassa’s crimes are still being uncovered

Bokassa first took refuge in the Ivory Coast in West Africa. But he soon showed up in a chateau in a Parisian suburb, where he entered a new career as a supplier of safari suits to African boutiques. President Giscard d’Estaing of France, meanwhile, made a personal donation to a Bangui charity school of $20,000 – which he said was the value of the diamonds Bokassa had given him.

Bokassa allegedly fed his enemies to his pet crocodiles

Cesare Borgia

O

f the Borgias, it is Lucrezia, perhaps, who has the worst reputation. But all she was was weak. It was her brother, the tyrant and murderer Cesare Borgia who seduced and tormented her, and then – mad with jealousy – scared off her first husband and murdered her second. After Cesare was wounded in battle and left to die, she lived a blameless life for another eleven years.

Cesare Borgia, like sister Lucrezia, was the bastard child of a courtesan and a cardinal who later, in 1492, became pope. He was immediately, aged 16, appointed Archbishop of Valencia; by 17, he was a cardinal. But it wasn’t enough for the unscrupulous spoiled brat. For what he wanted was power: power over people, power over the affairs of state. Not for nothing was he the model of Niccolo Machiavelli’s

The Prince

.

Power over people he satisfied sexually. He slept with every woman who attracted him, among them his sister and his brother’s intended wife, and regularly had his homosexual partners either poisoned or assassinated. The Venetian ambassador later wrote:

‘Every night four or five murdered men are discovered – bishops, prelates and others – so that all Rome is trembling for fear of being destroyed by the Duke Cesare.’

Power over the affairs of state, though, took more time. For elder brother Giovanni had been made head of the papal army and at the beginning of his reign the pope made a mistake: when the king of Naples died, he immediately recognized the king’s son as his successor. Charles VIII of France, believing he himself had a better claim, promptly invaded; and the Borgias were forced into a humiliating retreat. Cesare was taken as a hostage, and though he subsequently escaped, he wanted personal revenge for the humiliations he’d suffered at the hands of the French court. He murdered all those he could find who had witnessed them; and then had a group of Swiss mercenaries who’d broken into his mother’s house during the Frenchmen’s stay in Rome tortured to death.

As far as the politics of state were concerned, however, fate soon played into his hands. For brother Giovanni disgraced himself in a campaign against the Orsini family, who’d collaborated with the French. So Cesare had him assassinated and – abandoning his church titles – took over Giovanni’s role as his father’s military and political right-hand man. Allied to the French again by now, and married to the king of Navarre’s sixteen-year-old sister, he set about the business of bringing rebellious nobles into line and carving out a kingdom for himself in the area south of Venice.

As a commander, he was every bit as devious and ruthless as he had been as a cardinal. In one captured town he ordered forty of the prettiest virgins to be brought to him for deflowering. In another, he demanded that its female ruler be brought to his bed – and wrote gloatingly to his father about what transpired. In yet another he promised to give safe passage to its young master in return for his surrender, only to have him sent to Rome and tortured to death. His friends and allies also suffered. He double-crossed the Duke of Albino; had his own deputy hacked in two and displayed on a public square; and when he suspected disloyalty among those around him, invited them to a banquet and had them strangled.