100 Most Infamous Criminals (4 page)

Read 100 Most Infamous Criminals Online

Authors: Jo Durden Smith

Haarmann was born in 1879 in Hanover, and grew up a wanderer, a scrounger and petty thief – always in trouble with the law for pickpocketing and fraud and, on at least one occasion, sex offences with children. In 1913, the cops threw the book at him: he was sent to prison for five years; and by the time he emerged, the First World War had come and gone and Germany had plunged into chaos. Whole populations were on the move; the countryside and towns were full of homeless, rootless people, many of them teenage runaways desperate for a place to stay and work. Crime was universal; the black markets were thriving; people would buy and sell anything, without too many questions asked.

It was in this atmosphere that Haarmann, once out of prison, quietly set up a business as a meat-trader and dealer in second-hand clothes. Desperate for help against the rising tide of crime, the police soon recruited him as a spy – with the understanding that they wouldn’t look too closely at whatever he was up to in return. So the universally popular Haarman was free to go about his business – which involved hanging out with vagrant teenagers at the railroad station, taking them home for a meal or a bed and turning them into part of the food chain.

His relationship with the police was an effective cover: on one occasion, when forced to search his apartment, they gave it only a cursory look – and failed to notice the human head behind the oven. But so was his new profession as a butcher: the neighbours got used to the sounds of chopping, the bloodstained clothes and even a pail of blood carried down the stairs. Besides, Fritzi’s meat was so good.

In September 1919 – with the butchery and the second-hand-clothes business both doing well – Haarmann acquired a partner: a cold, tyrannical 20-year-old called Hans Grans, who encouraged him to expand. The stream of boys and young men disappearing into the apartment they took together steadily grew – and so did the number of parents, arriving from other districts of Hanover or from outside the city, looking for their children – who were, of course, nowhere to be found. For their heads and bones had been tossed into the river Leine; and their meat had passed through the digestive systems of unsuspecting citizens.

From time to time through the early 1920s, someone would mention that Haarmann had been seen with one of the disappeared, or that Grans had been spotted wearing another’s clothes. But by this time Haarman had become indispensable to the police. He’d even set up a detective agency of his own with a high police official, and was recruiting for a secret organization which was plotting the violent removal of the French from the occupied Ruhr. Though ghastly rumours were by now beginning to sweep through Hanover, about werewolves, butchers and cannibals stalking through the night – and though Hanover was beginning to be seen in German newspapers as a monster, an eater of children – still nothing was done.

Then, though, in May 1924, two human skulls were found in the river Leine and the police chief was finally forced to deal, not only with public outrage, but also with the pile of circumstantial evidence that by now linked the police’s favourite informer to the missing. He called in two detectives from Berlin and told them to follow Haarmann. They did, and promptly caught him attacking a teenager at the railroad station. He was arrested, and then his and Grans’s apartment was searched. Faced with the evidence – of blood on the walls and second-hand clothes that could be linked to the disappeared – Haarmann confessed. More than a quarter of a tonne of bones and skulls was later retrieved from the river.

Haarmann had invariably butchered his prey, he said at his trial, by tearing their throats out with his teeth. He’d almost certainly had sex with and mutilated them further before finally carving them up. He said he couldn’t remember how many victims there had been, perhaps thirty, perhaps forty. But investigators believed that he killed 138 in the past sixteen months alone. The total may have been as high as 600.

On December 19th 1924, he was found guilty of the murder of twenty-seven boys between the ages of 12 and 18. He was beheaded the next day. Grans, who on occasion had urged him to kill simply because he fancied a particular victim’s clothes, was sentenced to life imprisonment, later reduced to twelve years.

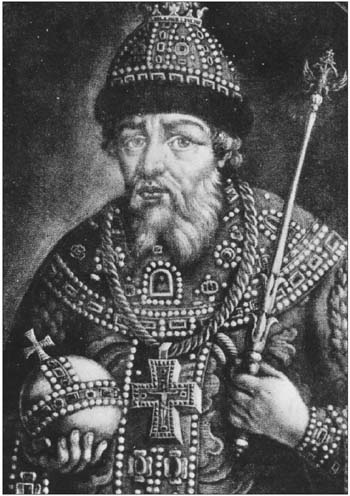

Ivan the Terrible

I

van the Terrible was born under a bad star. When his father, the Grand Duke of Muscovy, divorced his first wife in 1525 to marry Ivan’s mother, the patriarch of Jerusalem is said to have said:

‘If you do this evil thing, you shall have an evil son. Your nation shall

become prey to terror and tears.’

Terror and tears it duly got. For even in his lifetime Ivan became known as, not ‘the Terrible’ – a poor translation – but ‘the Dread.’

By the time he was eight years old, Ivan was an orphan – his father dead of an ulcer, his mother poisoned; and from then on, he later claimed, he had ‘no human care from any quarter.’ He grew up into a violent teenager – his first political act was to have one of the leaders of the warring factions beneath him assassinated and thrown to the dogs. Thirty of his followers were then hanged. One account says that Ivan liked to throw animals down from the Kremlin walls just to see them die; and that in the evenings – though full of daytime piety – he rampaged through the streets of Moscow with a gang of friends, beating up anyone who got in his way.

In 1547, Ivan had himself crowned as Tsar – Caesar – of all Russia, and shortly afterwards married Anastasia, the 15-year-old daughter of an influential member of his nobles’ council. She seems to have had a restraining influence on him; until she died 13 years later, he was a benevolent, if tough, ruler. He instituted reforms, attacked corruption, gave his people wider representation and access to the courts and reined in the powers of provincial governors. He also, by raking back territory from the Tartars, the descendants of the Mongol Khans, turned Russia into an imperial power.

In 1560, though, Anastasia died. Ivan soon imprisoned or exiled his closest advisers and became increasingly violent and irrational. In 1564, he withdrew from the capital completely and announced that he had laid down the office of Tsar. A deputation of churchmen and nobles rode out to see him and begged him to change his mind. He agreed, but only on condition that from now on he be allowed to govern without interference, and would have a free hand in dealing with traitors.

Ivan the Terrible – a tough and vicious ruler

At this point he began a bizarre social experiment. He divided the country into two halves, one of which was to be governed traditionally, and the other of which was from now on to be his personal domain. In his own half he soon unleashed the dark riders of a secret-service and assassination squad, the

oprichniki

, who instituted a reign of terror, wiping out all opposition to Ivan, killing more or less at will. Whole families were extirpated. Even the head of the Orthodox Church in Moscow was brutally murdered, while Ivan spent his time outside the capital, living a lifestyle, in the words of one historian,

‘blended of monastic piety, drunken debauchery and bizarre cruelty.’

The climax of the terror came in 1570, when the citizens of Novgorod were accused of being ready to hand their city over to the Poles. Ivan immediately rode northward, completely destroying the countryside in every direction. Then he built a wooden wall around the city, and for five weeks engaged in indiscriminate slaughter. Children were tortured in front of their parents – and vice versa. Women were impaled on stakes or roasted on spits; men were used in spear-hunts or fried alive in giant skillets. Tens of thousands were killed, and when Ivan was done, he rode back to Moscow for more execution-by-torture, this time of many of his advisers, in Red Square. So awesome did his reputation become that later when he invaded Livonia, one town garrison blew itself up rather than fall into his hands. He tortured to death all those who survived.

In 1572, Ivan abandoned the division of this kingdom to beat off a Tartar invasion that threatened Moscow. By now, in any case, all opposition to him had been emasculated. From now on, as in his youth, he see-sawed between monkish piety and unbridled carnality and rage. In 1581, after finding his son and heir Ivan’s pregnant wife not properly dressed, he threw her to the ground and kicked her. Then he lashed out at Ivan and fractured his skull. Both died within a few days.

By the time of Ivan’s own death, after seven marriages and innumerable mistresses, he was raddled with disease. As a British trader put it:

‘The emperor began grievously to swell in his cods [genitals], with which he had most horribly offended above fifty years, boasting of a thousand virgins he had deflowered and thousands of children of his begetting destroyed.’

In March 1584, acting in character, he called together sixty astrologers and told them to predict the day of his death, adding that if they got it wrong, they’d be burned alive. They said March 18th – and luckily for them he died one day before, before they could be proved wrong.

Bela Kiss

B

ela Kiss was forty years old when he moved with his young bride Maria to the Hungarian village of Czinkota in 1913. A plumber by trade, but obviously well-to-do, he bought a large house with an adjoining workshop and settled down to a quiet life, growing roses and collecting stamps. From time to time he would drive into Budapest on business, but otherwise his was an uneventful life. No one in the village ever thought to tell him that whenever he was away his wife was often seen out with a young artist called Paul Bihari.

Nor did anybody particularly remark on the fact that when he returned from the big city he started bringing oil drums back with him. Everyone, after all, knew that war was coming, and that fuel was likely to be scarce. When Kiss’s wife and the artist Bihari ended up disappearing from Czinkota, the villagers took it for granted that they’d eloped. Why, Kiss even had a letter from his wife that said as much.

Besides, poor man, he was clearly distraught at what had happened. He withdrew from village life – and it only became clear much later what the oil drums, which he continued from time to time quietly to bring back from Budapest, along with the occasional woman overnight guest, were really for…

After war came in August 1914, the reclusive Kiss was conscripted. While he served in the army, his house remained empty, its taxes unpaid; and then, in May 1916, news arrived that he’d been killed in action. His house was sold at auction for the unpaid taxes, and bought by a local blacksmith, who found seven oil-drums behind sheets of corrugated iron in the workshop. One day he opened one of them. It was full of alcohol – as were the rest of the drums. But in each one floated the body of a naked woman. When police subsequently searched the garden, they found the pickled bodies of another fifteen women, aged between 25 and 50, and that of a single young man. All of them had been garrotted.

It wasn’t long before police in Budapest picked up Kiss’s trail. He’d been placing advertisements in a newspaper, giving a post-office box number and claiming to be a widower anxious to meet a mature spinster or widow, with marriage in mind. Both the name and the address he’d given the newspaper proved false. But one of the payments he’d made to it had been by postal order, and when the signature on it was published in the press, a woman came forward and said it was that of her lover, Bela Kiss – and she produced a postcard sent from the front to prove it. When a photograph of Kiss was found and published in its turn, he was recognized as a frequent – and sexually voracious – visitor to Budapest’s red-light district. He’d apparently been using the savings he’d persuaded his victims to withdraw – in advance of their marriage – to feed his constant need for sex.

Kiss was, of course, dead. So the case was closed. But then a friend of one of his victims swore she’d seen him one day in 1919 crossing Budapest’s Margaret Bridge. Five years later a former French legionnaire told French police of a Hungarian fellow-soldier, with the same name as that used in Kiss’s ads, who’d boasted of his skill at garrotting. In 1932, Kiss was again recognized, this time in Times Square in New York. Had he swapped his identity with a dead man at the front and got away with it?

Ilse Koch

I

n 1950, when the ‘Bitch of Buchenwald’ Ilse Koch was finally tried for mass-murder in a German court, she protested that she had no knowledge at all of what had gone on in the concentration-camp outside Weimar. Despite the evidence of dozens of ex-inmates, she insisted:

‘I was merely a housewife. I was busy raising my children. I never saw anything that was against humanity!’

As hundreds of people gathered outside the court shouted ‘Kill her! Kill her!’ she was sentenced to life imprisonment.

Ilse Koch was born in Dresden, and by the age of 17 she was a voluptuous blue-eyed blonde: the very model of Aryan womanhood – and every potential storm-trooper’s wet dream. Enrolling in the Nazi Youth Party, she went to work in a bookshop that sold party literature and under-the-counter pornography and she was soon having a string of affairs with SS men. Then, though, she came to the attention of SS and Gestapo chief Heinrich Himmler, who selected her as the perfect mate for his then top aide, the brutish Karl Koch. Shortly after the wedding, when Koch was appointed commander of Buchenwald, she was installed in a villa near the camp, given two children, and then more or less forgotten by her husband, who was too busy staging multiple sex-orgies in Weimar to care.