100 Most Infamous Criminals (26 page)

Read 100 Most Infamous Criminals Online

Authors: Jo Durden Smith

Garrido had a history of abusing women

In 1972, he was charged with the rape of a 14-year-old girl whom he had plied with barbiturates. Phillip avoided doing time in prison when the girl refused to testify. Once clear of the rape charge, Phillip married Christine. The young couple settled 300 km (185 miles) northeast in South Lake Tahoe.

Christine got a job dealing cards at Harrah’s Casino, while her husband pursued his dream of becoming a rock star. Three years passed, and each day was blanketed in a haze induced by marijuana, cocaine and LSD. Phillip would spend hours masturbating while watching elementary school girls across the street, but the real object of his interest was a woman. Phillip had been following her for months, during which he developed a very elaborate plan, which he set in motion by renting a warehouse in Reno, 100 km (60 miles) to the south. He then fixed up the space, hanging rugs for soundproofing. A mattress was brought in, as were satin sheets, bottles of wine and pornographic magazines.

When his trap was set, Phillip took four tabs of LSD and attacked the woman. However, due to his drugged state, she managed to fight him off. Frustrated, Phillip drove to Harrah’s, where he asked one of his wife’s co-workers, Katie Callaway Hall, for a ride home. Katie was not as lucky as the intended victim. She ended up being raped repeatedly in the warehouse. After eight hours of pain and humiliation, Katie was rescued by a police officer whose eye had been drawn to the door, which had been left ajar.

This time, Christine did not stand by Phillip. After her husband’s arrest, she severed all ties. The divorce came through just as Phillip was beginning a 50-year prison sentence in Leavenworth, Kansas.

However, for Phillip, romance was still in the air. He began corresponding with the niece of a fellow inmate, Nancy Bocanegra, four years his junior. In 1981, the two were married in a ceremony conducted by the prison chaplain. Religion, it seemed, had turned into the focus of his life. A Catholic by birth, he converted, becoming a Jehovah’s Witness. Phillip’s extreme devotion to the denomination was cited by the prison psychologist as an indication that he would commit no further crimes.

Phillip was granted parole in 1988. With Nancy in tow, he returned to South Lake Tahoe, where they spent nearly three uneventful years.

On 10 June 1991, Phillip’s prison psychologist would be proven wrong. That morning, a man named Carl Probyn watched in horror as his 11-year-old stepdaughter was dragged into a grey sedan. Several of the girl’s friends had also witnessed the abduction – and yet no one was able to provide the licence plate number of the car that sped away.

The girl, Jaycee Dugard, soon found herself living in sheds, tents and under tarpaulins in the backyard of a house on Walnut Avenue, Antioch, Contra Costa County. The property belonged to Phillip’s mother, who suffered from dementia. Eventually, the old woman would be shipped off to a chronic care hospital. Jaycee, of course, remained on the property, where she would be subjected to 18 years of sexual abuse at Phillip’s hands. She bore her captor two children, both daughters, born in 1994 and 1997. Both would come to describe Jaycee as an older sister.

Phillip ran a print shop, Printing for Less, but he had very few repeat customers. That’s because those who gave him business were often subjected to bizarre ramblings. Some customers were shown a machine, through which the printer claimed he could communicate with God. Others might be treated to songs that Phillip had written about his attraction to underage girls.

In August of 2009, he walked into the San Francisco offices of the FBI to hand-deliver two weighty tomes he had written: ‘The Origin of Schizophrenia Revealed’ and ‘Stepping into the Light’. The latter was a personal story in which Phillip detailed how it was that he had come to triumph over his violent sexual urges. He approached Lisa Campbell, a special events coordinator at the University of California, Berkeley, with the idea of a lecture. Phillip was not alone when he made his proposal. Both his daughters sat in on the meeting, listening intently as their father spoke about his deviant past and the rapes he had committed.

It was Campbell’s report of this strange behaviour to Phillip’s parole officer that eventually brought an end to Jaycee’s nightmare. When confronted, on 26 August 2009, Phillip admitted to kidnapping Jaycee, adding that he was the father of her children. Both he and Nancy were taken into custody.

On 28 April 2011, Phillip pleaded guilty to Jaycee’s kidnapping, as well as 13 counts of sexual assault. Sitting next to her husband, Nancy pleaded guilty to the kidnapping, and one charge of aiding and abetting a sexual assault.

Nancy’s sentence was not nearly as harsh as that of her husband. Where Phillip received a term amounting to 431 years, Nancy was sentenced to 36 years in prison. Should she live a long life, Nancy Garrido will be 90 when she leaves prison.

Wayne Williams

I

n the early hours of May 22nd 1981, police on watch near a bridge over the Chattahoochee River in Atlanta, Georgia heard a sudden splash, and later saw a young black man driving away from the scene in a station-wagon. When they stopped the car, the driver identified himself as twenty-three-year-old Wayne Williams, a music-promoter and freelance photographer and he was allowed to go. The police, though, remained suspicious and put Williams under surveillance; when a body was discovered in the river two days later, they pulled him in.

The body was that of a twenty-seven-year-old black man, whom a witness later said he’d seen together with Williams, holding hands coming out of a cinema. Dog-hairs found on the corpse were found to match samples of those found in Williams’ house and in his car. It was, it seemed, an open-and-shut case. But a question remained: was Wayne Williams a serial killer? Was it he who’d been responsible for the deaths of twenty-six young blacks, teenagers and children in Atlanta over the past two years?

The first disappearances and discoveries had caused little fuss, given the city’s high crime-rate. Two teenagers had been found dead by a lake in July 1979; another had disappeared two months later. The fourth case, it was true, had caused some to-do, since the missing nine-year-old boy was the son of a locally well-known ex-civil rights worker. But it wasn’t until the number of disappearances had mounted and the bodies had begun to pile up that the police started to take serious notice.

Was Wayne Williams a serial killer?

Many felt Williams was used as a scapegoat, as much of the evidence against him was circumstantial

By the time a year was over, seven young blacks had been murdered – one of them a twelve-year-old girl tied to a tree and raped – and three more were still missing. The police were by now being accused of protecting a white racist killer. A number of bereaved parents formed a group and held a press conference to say that, even if the killer was black, the police were still not doing enough, simply because none of the victims was white. The police argued back that a white person, picking up kids in black neighbourhoods, would have stood out a mile and that the killer was probably a black teenager, someone who could get his victims’ trust.

None of this, though, made any difference, for the killings went on. Within a month, two more black children had disappeared; and the body count kept rising. One boy went missing that September; another in the following month. Civic groups offered a reward of $100,000; special programmes were offered to keep black kids off the streets; a curfew was even imposed. But the disappearances and the number of bodies discovered continued to rise. By May 1981, there were twenty-six dead, with one black kid still missing. The police had no leads at all. They were only watching the river that night because that’s where the latest victim had been found.

With Wayne Williams in custody, though, they did at least have a suspect; and, quite suddenly, they had witnesses who said they’d seen Williams with both the men found in the river. Others came forward to say that he’d tried to have sex with them, and one of these linked him to yet another victim The police then re-examined a number of the dead and found on eight others not only dog-hairs, but also fabric and carpet fibres that matched those in Williams’s bedroom.

Williams was only tried for the murders of the two men found in the river. The evidence against him was entirely circumstantial, but it was reinforced when the judge reluctantly allowed evidence from the other murders to be admitted. Gradually a picture of Williams was formed: the son of two schoolteachers who had grown up gifted and indulged, he had turned into a man obsessed with the idea of success – he worked on the fringes of show business. He also seemed to hate black people, even though he handed out leaflets offering black youths between the ages of eleven and twenty-one help with their musical careers.

Wayne Williams was found guilty on both counts of murder and sentenced to two consecutive life terms. Though many believed he was a scapegoat – and had been railroaded by the police – the murders of young blacks in Atlanta stopped with his imprisonment.

Aileen Wuornos

E

verything was against Aileen Wuornos, right from the beginning. Her father deserted her mother before she was born and her mother ran off from Rochester, Michigan not long afterwards, leaving her and her elder brother in charge of her grandparents, both of whom were drunks. Her grandfather beat both his wife and them; he allowed no friends in the house and wouldn’t even let them open the curtains. Malnourished and unable to concentrate in school, the children took to lighting fires with firelighter for amusement, and at the age of six, Aileen’s face was badly burned, scarred for life. By the time she reached puberty, she was already putting out to boys for food and drink, uppers, anything she could get. At thirteen she was raped by a friend of her grandparents. At fourteen, she was pregnant – and the child, she said, could have been anybody’s: the rapist’s, her grandfather’s, even her brother’s. The baby, a son, was put up for adoption immediately after birth.

Then, when her grandmother died of cancer in 1971, she and her brother were thrown out of their grandfather’s house and became wards of court. She dropped out of school and took up prostitution, while her brother robbed stores to feed an increasing drugs habit. Soon after her grandfather committed suicide in 1976, her brother died of throat cancer. He was only 21, a year older than she.

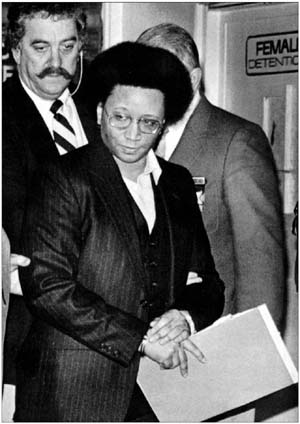

Wuornos’ killing spree ended when police identified her fingerprints on stolen goods

As if all this wasn’t enough, even her own genes seemed to be against her. For, quite apart from the cancers, the drinking and the suicide, the father she never met turned out to be a paranoid schizophrenic and a convicted paedophile. After spending time in mental hospitals for sodomizing children as young as ten, he hanged himself in a prison cell.

She had a couple of chances to go straight, it’s true. She was picked up while hitch-hiking by an older man, who became besotted with her and married her, and she also got $10,000 from a life-insurance policy her brother had taken out. But the husband she abused and beat, and she used the insurance money to buy a fancy car, which she promptly crashed. So she was soon back on the road as a hitchhiking hooker, hanging out with bikers, and getting regularly arrested: for cheque forgery, breaches of the peace, car-theft, gun-theft and holding up a convenience store. For the latter, she did a year in jail, and when she came out, she tried to commit suicide.