(12/20) No Holly for Miss Quinn (7 page)

Read (12/20) No Holly for Miss Quinn Online

Authors: Miss Read

Tags: #Fiction, #General, #England, #Country life, #Country Life - England - Fiction

Miriam hastily returned the handkerchief, and the wailing ceased as though a siren had been switched off.

"Perhaps I'd better take up my case," she said to Lovell, "and then I will cook a meal for us all."

"Goody-goody!" shouted Hazel.

"Gum-drops!" yelled Jenny. "That's what we say: 'Goody-goody-gum-drops!' Do you say that? Do you say: 'Goody-goody-gum-drops!' when you're pleased? We do, don't we, Hazel? We

always

say: 'Goody-goody—'"

"Not now you don't," said Lovell firmly. "Let Aunt Miriam have a few minutes' peace. Shall I take you up?"

"No, no," replied Miriam hastily, "I expect I'm in the usual room, aren't I?"

"I'll come with you," said Jenny.

"No, let me!" said Hazel.

"

Only one!

" bellowed Lovell, above the din. "You show Aunt Miriam to her room, Hazel, and then come down again. We'll set the table in the kitchen."

Miriam deposited her basket of groceries on the kitchen dresser, averting her eyes from the appalling state of the stove. Hazel was swinging on the newel post at the foot of the stairs, her dark hair flying behind her.

"Daddy's going to see Mummy this evening," she announced, prancing up the stairs in front of Miriam. "Can I go too?"

With a shock, Miriam realized that she had forgotten to ask after the mistress of the house in the turmoil of her arrival.

"We must ask Daddy," said she diplomatically. "The hospital staff may not want too many visitors all at once."

"But why not? I bet my mummy would like to see me, and I could tell her about the toffee we made, and having bread and peanut butter for lunch today."

By now they had traversed the long passage over the hall and Hazel flung open the door of the spare room. The light switch failed to work.

Miriam set down her heavy case and groped her way to a bedside table where she remembered that a reading lamp stood. Mercifully, it worked. Obviously, the main light needed a new bulb. She must see about that later on.

The room was cold and musty, and it was apparent that neither of the twin beds was made up. Lumpy rectangles composed of folded blankets showed through the candle wick bedspreads. She must face that job as soon as the children were in bed, and put in a hot bottle if she were to escape pneumonia in this chilly Norfolk climate. She had a strong suspicion that this room had not been used since her last visit in the early summer.

"Shall I help you to unpack?" enquired Hazel, eyeing the case hopefully.

"No. I'll do it later. You run downstairs and help Daddy. I'm just coming."

She hung up her coat on a peg on the back of the door. There was no coat hanger to be seen in the clothes' cupboard. What a house, thought Miriam! A vision of her own neat domain floated before her, and she had to wrench her mind to other matters to overcome the sudden flood of depression which engulfed her.

The bathroom was next door, chillier even than her own room. The bath was grimy. The wash basin was worse, and had what looked like a used medical plaster, recently stripped from someone's damaged finger, stuck to a cracked piece of soap. Miriam gingerly picked up this revolting amalgam and dropped it into an ancient enamel slop pail which seemed to do service as a wastepaper basket. Luckily, the bath rack provided her with a large tablet of Lifebuoy soap, and she was grateful for its disinfectant properties.

She unpacked a clean overall which she had prudently brought with her, and descended the stairs.

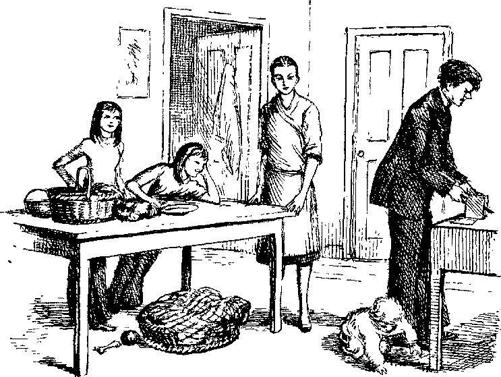

Lovell was slicing bread at the dresser, and Robin was sitting on the floor at his feet eating the crumbs that fell.

"Is it tea or supper?" asked Jenny. Miriam looked at Lovell.

"As they had so light a lunch," she said, "what about eggs and bacon? And sausages if you like. Do they have a meal like that before bedtime?"

"Oh, yes! Yes! We

always

have something like that, don't we?"

Their faces were rapturous. It was quite plain that they were hungry.

Lovell found her the frying pan, which was surprisingly clean, and she set about unpacking and cooking the provisions she had brought with her. Lovell, unasked, opened an enormous tin of baked beans and within twenty minutes Miriam's first meal was on the table.

There had been little culinary art in providing it and still less finesse in presenting it, straight from the pan to the waiting plates, but the children's evident relish as they demolished the meal gave her infinite satisfaction.

Now she found time to make amends and enquire after the patient.

"I'll know more when I've seen her this evening," said Lovell. "I'll help you to put this mob to bed and drive over to the hospital. You won't mind being left?"

"Of course not. I'll go tomorrow to see her."

"At the moment she is under observation, I gather. She's on a pretty strict diet, and having tests. If that doesn't have any result, then they'll think of surgery."

"What's surgery?" asked Hazel.

"It's cutting people up," explained Jenny kindly. "Like making chops at the butcher's."

At this point, Robin turned his mug upside down on the tablecloth and watched the milk creep towards the edge.

"He always does that when he's finished," said Jenny indulgently. "Isn't he a funny boy?"

Miriam rose to fetch a dishcloth, and began to mop up the mess. Only Lovell's presence restrained her from giving a sharp reprimand to the drowsy Robin, who now leant back sucking his thumb.

The little girls watched her efforts with interest.

"We bathed Copper with that cloth this afternoon. He was smelly, so we

squeezed

it out in soapy water, and gave him a

lovely

wash."

Miriam stopped her labors abruptly, and transferred the cloth to a battered tidy-bin beneath the sink. At this rate, she thought, a packet of J cloths must take priority on tomorrow's shopping list.

"We'll wash up," said Lovell, rising to his feet, "and I think Robin's ready for bed if you could cope with him."

At this, the comatose boy became instantly alert and shook his head violently.

"No! Dadda do! Dadda do!" he yelled, scarlet in the face.

"I think you'd better tonight," said Miriam swiftly. "He'll be more obliging when he knows me. We'll clear up here."

The two males vanished, and Miriam and the girls set about making order out of chaos. There seemed to be a dearth of tea cloths and a decidedly vague idea of where they were kept.

"They just hang about," said Hazel. "On the back of that chair usually."

"I mean the

clean

ones," said Miriam, her voice sharp with exasperation.

"I think they're in this drawer," said Jenny, struggling with an overfull dresser drawer stuffed with jam pot covers, pieces of string, two soup ladles, and what looked like half a colander. A few pieces of tattered cloth were intermingled with debris and, after close inspection, proved to be extremely ancient tea cloths.

"Aren't you getting excited about Christmas?" inquired Jenny, patting a spoon with one of the tattered rags, as her contribution to wiping the cutlery. "I am. I've asked Father Christmas for a painting set. Lots of different pots and brushes."

"I hope you'll get them," said Miriam civilly.

"Oh, she'll get them," announced Hazel, in a meaning way, "but whether

Father Christmas

will bring them, I don't know."

Jenny's face became suffused with angry color.

"Of course he'll bring them! My letter to him went

straight

up the chimney! Yours fell back and got burnt up, and serves you right."

"Now, now," said Miriam warningly. Really, she thought, I sound just like my mother! How stupid "Now, now!" sounded! Almost as idiotic as "Now then," a phrase which could bring on partial madness if considered for too long.

It was quite apparent that Hazel was wise to the myth of Santa Claus, while her sister was still touchingly a believer in the Christmas fairy. She must try and get a quiet word with the older child before too much damage was done.

Lovell reappeared as they were finishing. He looked exhausted and Miriam's heart was smitten.

"Go and sit by the fire, and I'll bring you some coffee," she said. "You don't need to set off immediately, do you?"

"Visiting hours are seven until eight-thirty," he said. "Goodness, it looks clean in here! I didn't give Robin a bath, just washed his face and hands. He's asleep already."

Scandalized, the little girls spoke together.

"But Robin

always

has a bath!"

"Annie

always

does him all over! He needs a bath."

"Mummy says we

must

have a bath before bed. Robin won't like it when he wakes up and finds he's all dirty still."

"He won't wake up," said their father shortly.

"We'll give him an extra long one tomorrow," promised Miriam, setting the kettle to boil, "as it's Christmas Eve!"

When Lovell had drunk his coffee and departed, carrying Miriam's bouquet and some magazines for Eileen, she took the girls up to the bathroom and bribed them into the steaming bath with one of her precious bath cubes.

"I'll come back in ten minutes to see if you are really clean," she told them, and left them to their own devices while she unpacked her case.

Later, scrubbed and sweet-smelling in their flowered night gowns, they held up their arms for a goodnight kiss, and Miriam admitted to herself that just now and again—for very brief periods—children could be very winning.

She descended the long staircase feeling a hundred years old. Fair acre and Holly Lodge seemed light-years away. This reminded her that she had promised to ring Joan.

But not before she had revived herself with coffee, she told herself, making for the kitchen. Peremptory barking greeted her. Copper stood pointedly by his empty plate.

"Amazingly enough," Miriam told him, "I know where your supper is!"

She tipped out the remains of a tin of dog food she had noticed in the larder, and Copper wolfed it down with relish.

He accompanied her to the fireside when she sank into her armchair with the cup of coffee and attempted to climb on her lap.

"Some other time, Copper, old boy," said Miriam faintly, fending him off. "It's as much as I can do to support myself."

She lay back and listened to the little domestic sounds of the old house. The fire whispered, a log shifted at its heart, the dog snored gently after his meal. Outside, the wind stirred the trees, and somewhere a distant door banged as the breeze caught it.

Gradually, the peace that surrounded her took effect. It had been a long day, and tomorrow would be an even harder one. But meanwhile, the children slept as soundly as the dog on the rug at her feet, and the night enfolded the quiet house.

When Lovell returned, he found his sister fast asleep in the arm chair.

Chapter 6

A CHRISTMAS MEMORY

M

ISS

Q

UINN

woke with a start, and sat bolt upright in bed.

Close at hand a church clock was striking midnight, and its pulsing rhythm filled the room.

Bewilderment and panic ebbed away, as she lay down again. Of course, she was safe in her brother Lovell's vicarage! This spare room, she remembered now, was close to the church tower.

It must be frosty tonight to be able to hear so clearly. Morning light would show rimy grass, no doubt, and ice-covered puddles, the little birds huddled patiently on sparkling twigs awaiting any bounty flung from the kitchen door.

The last stroke died away, and the old house sank back into silence. Sleep enveloped Lovell and the three children whom she had come to look after over Christmas, whilst their mother was in the hospital.

Poor Eileen, she thought! Was she asleep too, or lying awake, as she was herself? She envisaged the shadowy ward, a night nurse sitting in the one small pool of light, alert for any sound from a restless patient. How much luckier she was, to be here alone and free from pain!

With a sudden shock, she realized that it was now Christmas Eve. There would be wild excitement from her two nieces in the next few hours. Robin would be too young to understand, though no doubt he would be infected by the general fever of anticipation. Did the children hang up stockings here, she wondered, or pillow cases, as she and Lovell had done, in just such a drafty vicarage years ago?

One Christmas in particular she recalled vividly in that old Cambridgeshire house. She must have been about the same age as young Jenny asleep next door. Her milk teeth were beginning to wobble, and one in the front, she remembered, had been tipped back and forth so often by her questing tongue that her mother had begged her to "pull it out and have done with it." But fear had held her back, and even Lovell's pleas to "give it a good jerk" were in vain.

Lovell, two years older, was young Miriam's hero. He could climb to the top of their yew tree, while she stuck, trembling, half-way. He could make a whistle with his penknife and a hollow reed. He had bloodied Billy Boston's nose when he swore about their father, and he learnt geometry at the new day school in Cambridge.