1492: The Year Our World Began (5 page)

Read 1492: The Year Our World Began Online

Authors: Felipe Fernandez-Armesto

infinite riches in gold and silver and pearls and silks and clothes of silk and striped silk and taffeta and many kinds of gem and horses and mules and infinite grain and fodder and oil and honey and almonds and many bolts of cloth and furnishings for horses.

7

Prisoners could be ransomed for cash. The size of the booty determined the scale of a victory, and it was no praise for Alonso de Palencia to say of the Marquess of Cadiz that he gained “more glory than booty.” Only the nobility and their retainers served for booty. Most soldiers received wages, some paid by the localities where they served as militia, others directly out of royal coffers.

The money available was never enough, and Ferdinand and Isabella fell back on a cheap strategy: divide and conquer. In effect, for

much of the war, the Spanish monarchs seemed less focused on conquering Granada than on installing their own nominee on the throne. The Granadines fought each other to exhaustion. The invaders mopped up. The most important event of the early phase of the war was the capture in 1483 of Boabdil, who was then merely a rebellious Moorish prince. He was the plaything of seraglio politics. His mother, estranged from the king, fomented his opposition. His support came at first from factions at court but spread with the strain and failures of the war. A conflict that Mulay Hassan hoped would strengthen his authority ended by undermining it. A combined palace putsch and popular uprising drove Mulay Hassan to Málaga and installed Boabdil in his place in Granada. But the upstart’s triumph was short-lived. The internecine conflict weakened the Moors. Boabdil proved inept as a general and fell into Christian hands after a disastrous action at Lucena.

The Christians called Boabdil “the young king” from his nineteen years and “Boabdil the small” for his diminutive stature. His ingenuousness matched his youth and size. He had little bargaining power in negotiating for his release, and the terms to which he agreed amounted to a disaster for Granada. He recovered his personal liberty and obtained Ferdinand’s help in his bid to recover his throne. In return he swore vassalage. In itself, this might have been no great calamity, as Granada had always been a tributary kingdom. But Boabdil seems to have made the mistake of disbelieving Ferdinand’s rhetoric. Except as a temporary expedient, Ferdinand was unwilling to tolerate Granada’s continuing existence on any terms. Boabdil’s release was merely a strategy for intensifying Granada’s civil war and sapping the kingdom’s strength. The Spanish king had tempted Boabdil into unwilling collaboration in what Ferdinand himself called “the division and perdition of that kingdom of Granada.”

Boabdil’s father resisted. So did his uncle, Abū ‘Abd Allāh Muhammad, known as el Zagal, in whose favor Hassan abdicated, while the

Christians continued to make advances under cover of the Moorish civil war. Boabdil fell into Ferdinand’s hands a second time, and agreed to even harsher terms, promising to cede Granada to Castile and retain only the town of Guadix and its environs as a nominally independent kingdom. The Granadine royal family seems to have retreated into a bunker mentality, squabbling over an inheritance no longer worth defending. It is hard to believe that Boabdil can ever have intended to keep the agreement, or that Ferdinand can have proposed it for any reason other than to prolong Granada’s civil war.

For the invaders, the most important success of the succeeding campaigns was the capture of Málaga in 1487. The effort was costly. As Andrés de Bernáldez, priest and chronicler, lamented, “[T]he tax-gatherers squeezed the villagers because of the expenses of that siege.” The rewards were considerable. Castile’s armies in the war zone could be supplied by sea. The loss of the port impeded the Granadines’ communications with their coreligionists across the sea. The whole western portion of the kingdom had now fallen to the invaders.

Even in the face of Ferdinand’s advance, the Moors could not end their internal differences. But Boabdil’s partial defeat of el Zagal and return to Granada, with Christian help, had the paradoxical effect of strengthening Moorish resistance, although Boabdil’s was the weaker character and weaker party. Once Granada was in his power, he found it impossible to honor his treaty with Ferdinand and surrender the city into Christian hands. Nor was it in his interests to do so once el Zagal was out of the running.

By 1490 nothing but the city of Granada was left, occupying a reputedly impregnable position, but highly vulnerable to exhaustion by siege. Yet at every stage the war seemed to take longer than the monarchs expected. In January 1491 they set a deadline of the end of March for their final triumphant entry into Granada, but the siege began in earnest only in April. At the end of the year they were still in their makeshift camp nearby. Meanwhile the defenders had made many successful sorties, seizing livestock and grain-laden wagons,

and the besiegers had suffered many misadventures. Hundreds of tents in their camp burned in a conflagration in July, when a candle flame in the queen’s tent caught a flapping curtain. The monarchs had to evacuate their luxurious pavilion.

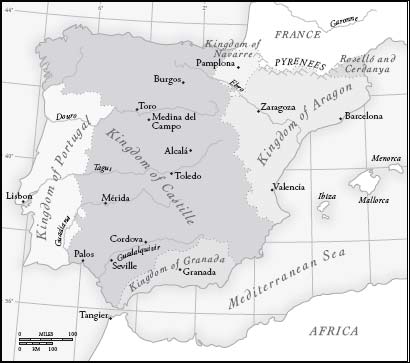

The Kingdom of the Iberian Peninsula, 1492.

The militant mood of the city’s inhabitants limited Boabdil’s freedom. The ferocity with which they opposed the Christians determined his policy. His efforts, formerly exerted in the Spaniards’ favor, were now bent on the defense of Granada. There was no way of supplying the city with food, and by the last stage of the war refugees crammed it to bursting. Yet even in the last months of 1491, when the besiegers closed around the walls of Granada, and Boabdil decided to capitulate, still the indomitable mood of the defenders delayed surrender. The last outlying redoubt fell on December 22. The Spanish troops entered the citadel by

night on the eve of the capitulation in order to avoid “much scandal”—that is, the needless bloodshed a desperate last resistance might otherwise have caused. Did Boabdil really say to Ferdinand, as he handed over the keys of the Alhambra on January 2, 1492, “God must love you well, for these are the keys to his paradise”?

8

“It is the extinction of Spain’s calamities,” exclaimed Peter Martyr of Anghiera, whom Ferdinand and Isabella kept at their court to write their history. “Will there ever be an age so thankless,” echoed Alonso Ortíz, the native humanist, “as will not hold you in eternal gratitude?” An eyewitness of the fall of the city called it “the most distinguished and blessed day there has ever dawned in Spain.” The victory, according to a chronicler in the Basque country, “redeemed Spain, indeed all Europe.”

9

In Rome, bonfires burned all over the city, nourished into life in spite of the rain. By order of the pope, the citizens swept Rome’s streets clean. When dawn broke, the bell at the summit of the Capitoline Hill in Rome began ringing with double strokes—a noise never otherwise heard except on the anniversary of a papal coronation, or to announce the feast of the Assumption of the Virgin in August. But it was a cold, wet morning in early February 1492 when the news of the fall of Granada was made public. Equally unseasonally, celebratory bullfights aroused such enthusiasm that day that numerous citizens were gored and killed before the bulls were dispatched. Races were held—separately for “old and young men, boys, Jews, asses and buffaloes.” An imitation castle was erected, to be symbolically stormed by mock assailants—only the ceremony had to be deferred because of the rain. Pope Innocent VIII, already so old and infirm that his entourage were in permanent fear for his life, chose to celebrate mass in the hospital of the Church of St. James the Great, the patron saint of Spain. A procession of clergy joined him there from St. Peter’s, in a throng so irrepressibly tumultuous that he had to postpone his sermon because of the noise they made.

10

The pope called the royal conquerors “athletes of Christ” and conferred on them the new title, which rulers of Spain bore ever after, of “Catholic Monarchs.” The joy evoked in Rome echoed through Christendom.

Yet every stage of the conquest brought new problems for Ferdinand and Isabella: the fate of the conquered population; the disposal, settlement, and exploitation of the land; the government and taxation of the towns; the security of the coasts; the assimilation and administration of the conflicting systems of law; and the difficulties arising from religious differences. The problems all came to a head in the negotiations for the surrender of the city of Granada. The Granadine negotiators proposed that the inhabitants would be “secure and protected in their persons and possessions,” except for Christian slaves. They would retain their homes and estates, and the king and queen would “honor them and regard them as their subjects and vassals.” Muslims would enjoy the right to continue practicing Islam, even if they had once been Christians, and to keep their mosques with their schools and endowments. Mothers who converted to Christianity would have to renounce gifts received from their parents or husbands, and lose custody of their children. The native merchants of Granada would have free access to markets anywhere in Castile. Citizens who wished to migrate to Muslim lands could keep their belongings or dispose of them at a fair price and remove the proceeds from the realm. All clauses were to apply to Jews as well as Muslims.

Astonishingly, the monarchs accepted all these terms—on the face of it, an extraordinary departure from the tradition established by earlier Castilian conquests. Except in the kingdom of Murcia, to the east of Granada, Castilian conquerors had always expelled Muslims from land they conquered. In effect, this meant scrapping the entire existing economic system and introducing a new pattern of exploitation, generally based on ranching and other activities practicable with small populations of new colonists. Initially, the deal struck with Granada more resembled the traditions established in the Crown of Aragon, in Valencia, and in the Balearic Islands, where the conquerors did all they could to ensure economic continuity, precisely because they lacked the manpower to replace the existing population. Muslims were too numerous and too useful. In the kingdom of Valencia, the running of agricultural estates depended on the labor of Muslim peasants, who continued to be

the bedrock of the regional economy for well over a hundred years. Granada, however, was not like Valencia. It could prosper even without the Muslim population, whose fate, despite the favorable terms of surrender, remained insecure.

By Granada’s terms of surrender, the Moors, as subjects and vassals of the monarchs, not only could remain to keep the economy going, but also incurred obligations of military service. Ferdinand and Isabella even attempted to organize them to provide coastal watches against invasion, but that part of their policy was outrageously overoptimistic. If Maghrebis or Turks invaded, most Christians were in no doubt of whose side the defeated Moors would favor. As Cardinal Cisneros wrote during his stay in Granada, “Since there are Moors on the coast, which is so near to Africa, and because they are so numerous, they could be a great source of harm were times to change.”

At first, the conquerors seemed anxious to act in good faith. Ferdinand, despite his reluctance to have more Muslim subjects, acted as if he realized that the ambition of an all-Christian Spain, “constituted to the service of God,” was impractical. The governor and archbishop of Granada shared power with Muslim “companions,” and for a while their collaboration kept the peace. The companions ranged from respected imams, such as Ali Sarmiento, who was reputedly a hundred years old and immensely rich, to shady capitalists, such as al-Fisteli, the money lender who served the new regime as a tax collector. In 1497, Spain offered refuge to Moors expelled from Portugal. So expulsion was not yet imminent.

Yet if the monarchs had kept to the terms of the bargain they made when the city fell, it would have been honorable, but it would also have been incredible. Ferdinand, as we have seen, declared in correspondence with the pope their intention of expelling the Muslims. In 1481 he wrote in similar terms to the monarchs’ representative in the northwest of Spain: “[W]ith great earnestness we now intend to put ourselves in readiness to toil with all our strength for the time when we shall con

quer that kingdom of Granada and expel from all Spain the enemies of the Catholic faith and dedicate Spain to the service of God.”

11

Most of the conquered population did not trust the monarchs. Many took immediate advantage of a clause in the terms of surrender that guaranteed emigrants right of passage and provided free shipping. Granada leeched refugees. Boabdil, whose continued presence in Spain the monarchs clearly resented, left with a retinue of 1,130 in October 1493.

Indeed, the policy of conciliating the conquered Moors, while it lasted, was secondary to the monarchs’ main aim of encouraging them to migrate. This had the complementary advantages of reducing their potentially hostile concentration of numbers and of freeing land for resettlement by Christians. The populations of fortified towns were not protected by the terms negotiated for the city of Granada. They had to leave. Their lands were confiscated. Many fled to Africa.

Eventually, Ferdinand and Isabella abandoned the policy of emigration in favor of expulsion. In 1498, the city authorities divided the city into two zones, one Christian, one Muslim—a sure sign of rising tensions. Between 1499 and 1501, the monarchs’ minds changed as turbulence and rebellion mounted among the Moors and most of them evinced unmistakable indifference to the chance to convert to Christianity. The fate of former Christians provoked violence when the Inquisition claimed the right to judge them. There were only three hundred of them, but they were disproportionately important: “renegades” to the Christians, symbols of religious freedom to the Moors. Muslim converts to Christianity were exempt from the Inquisition’s ministrations for forty years. The new archbishop of Granada, Hernando de Talavera, procured that concession for them, partly because he disliked and mistrusted the Inquisition, and partly because he realized that converts needed time to adjust to their new faith. Apostates, however, were in a special category. It was hard to fend the Inquisition off. In 1499, Ferdinand and Isabella sent the primate of Spain, Cardinal Cisneros, to sort the problem out.