1492: The Year Our World Began (10 page)

Read 1492: The Year Our World Began Online

Authors: Felipe Fernandez-Armesto

When he sent one hundred masons and carpenters to build the fort of São Jorge, therefore, he was doing something new: inaugurating a policy of permanent footholds, disciplined trading, and royal initiatives. The natives could see and fear the transformation for themselves. A local chief said that he had preferred the “ragged and ill dressed men who had traded there before.”

24

Another prong of the new policy was the centralization of the African trade at Lisbon, in warehouses below the royal palace, where all sailings had to be registered and all cargo stored. An even more important element in João’s plan was the cultivation of

friendly relations with powerful coastal chieftains: the Wolof chiefs of Senegambia; the rulers—or “obas,” as they were called—of the lively port city of Benin; and ultimately—much farther south—the kings of Kongo. Conversion to Christianity was not essential for good relations—but it helped. In Europe, it served to legitimize Portugal’s privileged presence in a region where other powers coveted the chance to trade. In Africa, it could create a bond between the Portuguese and their hosts.

Dom João therefore presided over an extraordinary turnover in baptisms and rebaptisms of rapidly apostatizing black chiefs. In one extraordinary political pantomime in 1488, he entertained an exiled Wolof potentate to a full regal reception, for which the visitor was decked out with European clothes and the table laden with silver plate.

25

Farther east along the coast, Portuguese missionary effort was still feeble, but the fort of São Jorge was Christianity’s shopwindow in the region, contriving an attractive display. Its wealth and dimensions were modest, but mapmakers depicted it as a splendid place, with high fortifications, pennanted turrets, and gleaming spires—a sort of black Camelot. It had no explicit missionary role, but it did have resident chaplains, who became foci of inquiries from local leaders and their rivals, who realized that they could get help in the form of Portuguese technicians and weapons if they expressed an interest in Christianity. The obas of Benin played the game with some skill, never actually committing to the Church but garnering aid like supermarket customers targeting “special offers.” Not much came of any of the contacts, in terms of real Christianization, and in competition in the region neither Christianity nor Islam was very effective at first. But West Africa had become what it has remained ever since: an arena of spiritual enterprise in which Islam and Christianity contended for religious allegiance.

Farther south, where Portuguese ships reached but where Muslim merchants and missionaries were unknown, was the kingdom of Kongo. Here people responded to Christianity with an enthusiasm wholly disproportionate to Portugal’s lackluster attempts at conversion. The

kingdom dominated the Congo River’s navigable lower reaches, probably from the mid–fourteenth century. The ambitions of its rulers became evident when Portuguese explorers established contact in the 1480s. In 1482, battling against the Benguela Current, Diogo Cão reached the shores of the kingdom. Follow-up voyages brought emissaries from Kongo to Portugal and bore Portuguese missionaries, craftsmen, and mercenaries in the reverse direction.

In Kongo, the rulers sensed at once that the Portuguese could be useful to them. They greeted them with a grand parade, noisy with horns and drums. The king, brandishing his horsetail whisk and wearing his ceremonial cap of woven palm fiber, sat on an ivory throne smothered with the gleaming pelts of lions. He graciously commanded the Portuguese to build a church, and when protesters murmured at the act of sacrilege to the old gods, he offered to put them to death on the spot. The Portuguese piously demurred.

On May 3, 1491, King Nzinga Nkuwu and his son, Nzinga Mbemba, were baptized. Their conversion may have started as a bid for help in internal political conflicts. The laws of succession were ill defined, and Nzinga Mbemba, or Afonso I, as he called himself, had to fight for the succession. He attributed his victory to battlefield apparitions of the Virgin Mary and St. James of Compostela—the same celestial warriors that had often appeared on Iberian battlefields in conflicts against the Moors and would appear again on the side of Spain and Portugal in many wars of conquest in the Americas. Kongo enthusiastically adopted the technology of the visitors and embraced them as partners in slave raiding in the interior and warfare against neighboring realms. Christianity became part of a package of aid from these seemingly gifted foreigners. The royal residence was rebuilt in the Portuguese style. The kings issued documents in Portuguese, and members of the royal family went to Portugal for their education. One prince became an archbishop, and the kings continued to have Portuguese baptismal names for centuries thereafter.

The Portuguese connection made Kongo the best-documented kingdom in West Africa in the sixteenth century. However Afonso I came

to Christianity in the first place, he was sincere in espousing it and zealous in promoting it. Missionary reports extolled the “angelic” ruler for knowing

the prophets and the gospel of Our Lord Jesus Christ and all the lives of the saints and everything about our sacred mother the church better than we ourselves know them…. It seems to me that the Holy Spirit always speaks through him, for he does nothing but study, and many times he falls asleep over his books, and many times he forgets to eat and drink for talking of Our Lord,…and even when he is going to hold an audience and listen to the people, he speaks of nothing but God and His saints.

26

Thanks in part to Afonso’s patronage, Christianity spread beyond the court. “Throughout the kingdom,” the same writer informed the Portuguese monarch, Afonso

sent many men, natives of the country, Christians, who have schools and teach our saintly faith to the people, and there are also schools for girls where one of his sisters teaches, a woman who is easily sixty years old, and who knows how to read very well and who is learned in her old age. Your Highness would rejoice to see it. There are also other women who know how to read and who go to church every day. These people pray to Our Lord at mass and Your Highness will know in truth that they are making great progress in Christianity and virtue, for they are advancing in the knowledge of the truth; also, may Your Highness always send them things and rejoice in helping them and, for their redemption, as a remedy, send them books, for they need them more than any other things for their redemption.

27

Afonso may have loved books. His own priority, however, was to ask for what we would now call medical aid—physicians, surgeons,

apothecaries, and drugs—not so much in admiration of Western medicine as in fear of the link between traditional cures and pagan practices, for, as Afonso explained to the King of Portugal,

we always have many different diseases, which put us very often in such a weakness that we reach almost the last extreme; and the same happens to our children, relatives and natives owing to the lack in this country of physicians and surgeons who might know how to cure properly such diseases. And as we have got neither dispensaries nor drugs which might help us in this forlornness, many of those who had been already confirmed and instructed in the holy faith of Our Lord Jesus Christ perish and die; and the rest of the people in their majority cure themselves with herbs and spells and other ancient methods, so that they put all their faith in the said herbs and ceremonies if they live, and believe that they are saved if they die; and this is not much in the service of God.

28

Not all Afonso’s efforts to convert his people were entirely benign. The missionaries also commended him for “burning idolaters along with their idols.” How much the combination of preaching, promotion, education, and repression achieved is hard to gauge. Portugal stinted the resources needed to Christianize Kongo effectively. And the rapacity of Portuguese slavers hampered missionary efforts. Afonso complained to the king of Portugal about white slavers who infringed the royal monopoly of European trade goods and seized slaves indiscriminately. “In order to satisfy their voracious appetite,” they

seize many of our people, freed and exempt men, and very often it happens that they kidnap even noblemen and the sons of noblemen, and our relatives, and take them to be sold to the white men who are in our Kingdoms; and for this purpose they have concealed them; and others are brought during the night so that they might not be recognized. And as soon as they are taken by the white men they are

immediately shackled and branded with fire…. And to avoid such a great evil we passed a law so that any white man living in our Kingdoms and wanting to purchase goods in any way should first inform three of our noblemen and officials of our court whom we rely upon in this matter,…who should investigate if the mentioned goods are captives or free men, and if cleared by them there will be no further doubt nor embargo for them to be taken and embarked. But if the white men do not comply with it they will lose the aforementioned goods. And if we do them this favor and concession it is for the part Your Highness has in it, since we know that it is in your service too that these goods are taken from our Kingdom.

29

Despite the limitations of the evangelization of Kongo, the dynamism of Christianity south of the Sahara set a pattern for the future. The region was full of cultures that adapted to new religions with surprising ease. Until the intensive missionary efforts of the nineteenth century, Christianization was patchy and superficial, but Christians never lost their advantage over Muslims in competing for sub-Saharan souls.

By adhering to Christianity, the Kongolese elite compensated, to some extent, for the isolation and stagnation of Christian East Africa at about the same time. Christianity had been the religion of Ethiopia’s rulers since the mid–fourth century, when King Ezana began to substitute invocations of “Father, Son, and Holy Spirit” for praise of his war god in the inscriptions that celebrated his campaigns of conquest and enslavement. The empire’s next thousand years were checkered with disaster, but Ethiopia survived—an aberrant outpost of Christendom, with its own distinctive heresy. For the Ethiopian clergy subscribed to the doctrine, condemned in the Roman tradition in the mid–fifth century, that Christ’s humanity and divinity were fused in a single, wholly divine nature. In the late fourteenth century, in near-isolation from contact with Europe, the realm again began to reach beyond its mountains to dominate surrounding regions. Monasteries became schools of

missionaries, whose task was to consolidate Ethiopian power in the conquered pagan lands of Shoa and Gojam. Rulers, meanwhile, concentrated on reopening their ancient outlet to the Red Sea and thereby the Indian Ocean. By 1403, when King Davit recaptured the Red Sea port of Massaweh, Ethiopian rule stretched into the trade route along the Great Rift Valley, where slaves, ivory, gold, and civet headed northward, generating valuable tolls.

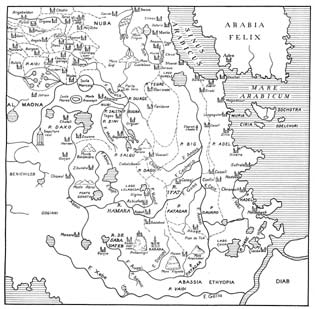

Map redrawn from Fra Mauro’s Venetian Mappamundi of the 1450s, showing how well informed Latin Christendom was about Ethiopia.

Fra Mauro’s Ethiopia map from O. G. S. Crawford,

Ethiopian Itineraries

, circa 1400–1524 (Cambridge, 1958). Courtesy of The Hakluyt Society. The Hakluyt Society was established in 1846 for the purpose of printing rare or unpublished Voyages and Travels. For further information please see their website at: www.hakluyt.com.

Yet by the time of the death of King Zara Yakub, toward the end of the 1460s, expansion was straining resources, and conquests stopped. Saints’ lives are a major source for Ethiopian history in this period. They tell of internal consolidation rather than outward expansion as monks con

verted wasteland to farmland. The kingdom began to feel beleaguered, and rulers sought outside help, looking as far as Europe for allies. European visitors were already familiar in Ethiopia, for Ethiopia’s Massaweh Road was a standard route to the Indian Ocean. Italian merchants anxious to grab some of the wealth of the Indian Ocean for themselves would head up the Nile as far as Keneh, where they joined camel caravans across the eastern Nubian desert for the thirty-five-day journey to the Red Sea. Encouraged by these contacts, Ethiopian rulers sent envoys to European courts and even flirted with the idea of submitting the Ethiopian church to the discipline of Rome. In 1481, the pope provided a church to house visiting Ethiopian monks in the Vatican garden.

The kingdom was still big enough and rich enough to impress European visitors. When Portuguese diplomatic missions began to arrive—the first, in the person of Pedro de Covilhão, in about 1488; a second in 1520—they found “men and gold and provisions like the sands of the sea and the stars in the sky,” while “countless tents” borne by fifty thousand mules transported the court around the kingdom.

30

Crowds of two thousand at a time would line up for royal audiences, marshaled by guards on plumed horses, caparisoned in fine brocade. To the ruler of Ethiopia, Negus Eskendar, Covilhão was immediately recognizable as a precious asset, whom he retained at his court with lavish rewards.