A Dance with Death: Soviet Airwomen in World War II (36 page)

Read A Dance with Death: Soviet Airwomen in World War II Online

Authors: Anne Noggle

On the second day of the war I went to the Central Body of the

Komsomol League in Moscow and was enrolled among its staff, and

my department received a lot of letters from female pilots asking to

be permitted to go to the front. There were so many letters that

Marina Raskova, who later on founded the regiments, calculated that

the number was equal to that required to form three regiments. This

was the start of the female regiments. I too submitted an application

asking to be admitted to such a regiment. And when the regiments

were formed, I was appointed the secretary of the party organization

of the 586th Fighter Regiment with the rank of senior lieutenant,

designated by three small stars on the ribbons. By the end of the war I

was a captain, designated by four small stars.

When the girls came to join the army they all looked like girls,

with long, curly hair and high heels. The first thing to do was make

them look all alike, like soldiers, with hair cut short, military boots,

and pants. It was really very difficult to make the girls part with their

hair and feminine things and put them into men's military clothing.

In the army air force it was obligatory for the girls to jump with a

parachute, especially the pilots. The commander of our regiment

didn't make a single jump because she was deadly afraid of it. They

even threatened that she would be relieved of command, but she still

said, "No, I'm afraid to do that!" The commander of our squadron,

Tamara Pamyatnykh, didn't make a single jump either. In 1943, near

Voronezh, she and her wingman intercepted German bombers, and in

that fight Pamyatnykh's plane was hit and she had to jump!

About the uniforms: we were not allowed to do anything about

those too large boots. Once in the morning, when we were in training, we all lined up, and Raskova faced us and gave the command: to

the right. One of the girls turned to the right, but her boots remained

in the same place, and she swerved and the boots didn't move.

Raskova was a very strict woman, and she was young, just twentyseven; she could have reprimanded her, but she didn't- she burst out

laughing. Soon after that one girl was to show that she could pack her

parachute rapidly and then jump. When she was jumping one boot

fell off, then the other, then the leg wrappings that replaced socks,

and only then did she come to the ground- barefoot! Then we were

allowed to resew the boots. We have a saying in Russia: if there hadn't

been an unhappy incident there never would be a happy one!

Valentina Lisitsina, 586th regiment

When the girls were ordered to cut their hair very short, only one

girl, Lilya Litvyak, refused to do it. I came to report to Raskova and

said, "Comrade Major, your order has been carried out; everyone has

had their hair cut but Lilya," and Raskova replied, "My order has not

been fulfilled." I came to Lilya with tears in my eyes and asked her to

please to do it, and at last she agreed.

When we were at the front, one of the regimental duties was to

protect the aircraft of important people. Zoya Pozhidayeva was assigned along with five other female pilots and six male pilots from

another regiment to guard the plane of a government official. When

the aircraft landed and the guard planes took off to fly back to their

respective airfields, Zoya decided to trick one of the male pilots and

flew around his plane several times. He cursed her with very bad

names. When our planes landed and our commander asked if the

flight had been successful, Zoya said, "Yes, but we should never fly

with the men again because they cursed and called me bad names."

Our commander called the commander of the male regiment and told

him that our girls refused to fly with them anymore because of their

bad behavior. The male commander lined up the whole crew and

said, "How could you do that? How dare you do that? There were girls

in those planes, and you have to behave yourselves!" And the pilot

who had done the cursing said, "Oh my God, I didn't know they were girls! I would have never opened my mouth and uttered such words!"

He decided to apologize and got into his plane and flew to our regiment. He apologized to Zoya for what he had done, and they became

friends and corresponded throughout the war, and when it ended

they were married.

Besides my work, I was responsible for some amateur concerts, and

also our regimental newspaper that we wrote ourselves-not printedwritten by hand. The duty of a political activist was not only to speak

in the meetings and to do reports describing the political and military

situation but mostly to have very close contact with all the girls and

talk with them individually. When a girl was assigned a mission to

fly but had to wait for some time in the cockpit before the mission, I

would come up to her and talk about politics. The girls used to say,

"Well I'm sorry, but go to hell with your politics, let's discuss love

affairs!" They were patriots and would gladly talk politics, but they

would say that it might be their last flight and they might not return,

and they didn't want to talk politics, they wanted to review their

emotions. There was a pressure that filled their bodies, and those

personal talks helped me get to know them better.

I knew everything about the family affairs of almost every girl,

their love affairs, everything. Not like a mother, but still I was very

close to them; they were frank. Moreover, such intimate talks eased

pressure in their hearts. Before the flight they were fearless, but after

they returned from a mission they felt a nervous strain and emotional

outburst.

One day the two girls who flew a mission in which they engaged

forty-three bombers returned and were having a rest under the wings

of their planes. I asked them if they experienced great fear while

fulfilling their missions, and they said, "Yes, very much," and their

legs were trembling still. One of them, Raisa, said that she was so

frightened and overstrained that she would never fly again. Well, after

she calmed down and pulled herself together, she went on performing

her missions-it was an immediate reaction.

It was especially hard mentally and emotionally to come through

the experience of losing our friends. It was a great strain, and it took

strength for me to somehow raise their spirits. In our regiment twelve

girls perished. When the brilliant commander of one of our squadrons

returned from a mission and suddenly crashed before our eyes and

died, we wanted to find her body, her remains, and we didn't find

anything at all. There was no special ceremony when someone perished. There was a coffin, and we stood beside it and said something about the dead person and cried, and then buried them right there in

the fields.

Leaving headquarters (a dugout) for a mission in 1942, 586th regiment

Our first losses were at our training site at Engels. We lost two

crews, two pilots in each aircraft. It was a shock for us and a misery,

and we sobbed beside their coffins, and Raskova turned to all of us

and said, "My darlings, my girls, squeeze your heart, stop crying, you

shouldn't be sobbing, because in the future you have to face so many

of them that you will ruin yourselves completely." And since that

time we have suffered great losses and overcome the gravest experiences, and we were, and we remain, the closest of friends. We swore

that after the war ended, each year we would have our reunion. And

we do.

Senior Sergeant Inna Pasportnikova,

mechanic

There is a monument to Lilya Litvyak, and each star on it is for a

German aircraft she shot down. When they erected the monument to

Lilya, they left a blank space on the stone so that one day "Hero of the

Soviet Union" could be added. They searched for her plane and body

for fifteen years. Only in May, 199o, was she awarded the Gold Star. Lilya had crash-landed in a field

and died there, and persons unknown buried her under the

wing of the plane. Later people

came and disassembled the aircraft, and no one knew Lilya

was buried there. I was her mechanic when she joined the

male regiment at Stalingrad but

not before, in the female regiment. She flew the Yak fighter

during the war. When the war

broke out, she was a flight

instructor.

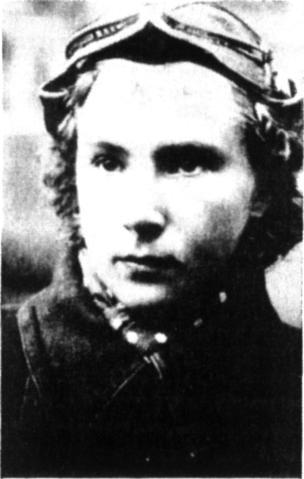

Lilya Litvak, 586th Fighter Regiment

Engels, on the Volga River,

was our training base. We went

to Engels in October, 1941, and

were given our winter uniforms

in November. Once, when we

were all standing in formation,

Lilya was told to step forward.

She was in winter uniform, and

she had cut the tops off of her high fur boots and made a fur collar for

her winter flying suit. Marina Raskova, our commander, asked when

she had done this, and Lilya replied, "During the night." Lilya wanted

to have this fashion. Raskova said that during the next night she

shouldn't sleep but must take the fur collar off and put it back on the

boots. She was arrested and put in an isolation room, and all night she

was changing it back. This was the first time she was noticed by the

other women. She was a very small person. It was strange: the war

was going on, and this blonde, this girl, was thinking about her collar.

I wondered, What kind of a pilot will she make when she doesn't

think of more important things than the collar and how she looks!

After this I started to watch her, and she was one of the best pilots;

she flew her program perfectly. I never thought the time would come

when I would be her mechanic.

Our regiment, the 586th Fighter Regiment (Air Defense), was the

first to be formed from the training regiment with about twenty

pilots. In the beginning there were only two squadrons, and the regiment's first assignment was to protect Saratov city on the Volga

River. The most important thing there was the bridge across the river-the only bridge in that area. The first woman pilot to shoot

down a German aircraft in that vicinity was Valeriya Khomyakova,

who was later killed in a dogfight.

In September, 1942, some of our pilots, including Lilya, were sent

to different male regiments protecting Stalingrad during that terrible battle, and I was sent there also, to he Lilya's mechanic. Lilya

bleached her hair white, and she would send me to the hospital to

get hydrogen peroxide liquid to do it. She took pieces of parachute,

sewed them together, painted it different colors, and wrapped it

around her neck.

Lilya was very fond of flowers, and whenever she saw them she

picked them. She would arrive at the airfield early in the morning in

the summer, pick a bucket of flowers, and spread them on the wings

of her plane. She especially loved roses. In the winter she wrote to her

mother in Moscow asking for a picture with roses. Her mother

couldn't find a picture, so she asked me to write to my mother, who

sent a postcard with roses, but the roses were yellow and Lilya liked

red. She put the picture of roses on the left side of the instrument

panel and flew with it. She was pretty and thin and looked like the

actress Serova, who was quite famous. Lilya was born in 1921, and at

that time she was twenty years old and I was twenty-one.