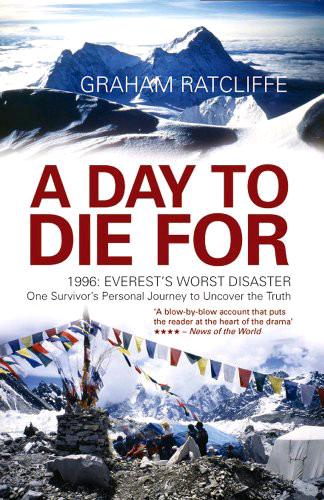

A Day to Die For: 1996: Everest's Worst Disaster - One Survivor's Personal Journey to Uncover the Truth

Authors: Graham Ratcliffe

Tags: #General, #Biographies & Memoirs, #Memoirs, #Specific Groups, #Biographies, #Travel, #Nepal, #Adventurers & Explorers, #Asia, #Mountaineering, #Education & Reference, #Mountain Climbing, #Sports & Outdoors

BOOK: A Day to Die For: 1996: Everest's Worst Disaster - One Survivor's Personal Journey to Uncover the Truth

13.16Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

1996: Everest’s Worst Disaster – One Survivor’s Personal Journey to Uncover the Truth

Graham Ratcliffe

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licenced or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Epub ISBN: 9781907195990

Version 1.0

Copyright © Graham Ratcliffe, 2011

All rights reserved

The moral right of the author has been asserted

First published in Great Britain in 2011 by

MAINSTREAM PUBLISHING COMPANY (EDINBURGH) LTD

7 Albany Street

Edinburgh EH1 3UG

ISBN 9781845966386

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any other means without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for insertion in a magazine, newspaper or broadcast

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

For Catherine, Angela, Amy and Sophia

And in memory of friends lost in pursuit of their dreams

Facts are stubborn things; and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passions, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence.

– Joey Adams (Joseph Abramowitz, 1911–99)

Disclaimer

It was MacGillivray Freeman Films, as producers, who organised the shooting of the IMAX documentary film

Everest

in the spring of 1996. The IMAX Corporation were not involved in the planning of the Everest expedition to shoot the film, or in any of its decision-making.

Everest

in the spring of 1996. The IMAX Corporation were not involved in the planning of the Everest expedition to shoot the film, or in any of its decision-making.

Within the text of this book, the IMAX Corporation and the films shown in their large-screen cinemas are referred to using capitals (as in their trademark) and the Imax expedition, as it was known, with a capital letter and the rest in lower case.

The fact that the expedition was called the ‘MacGillivray Freeman IMAX/IWERKS Expedition’, which is referred to as the Imax expedition in this book, does not mean they and the IMAX Corporation are one and the same. Any references in the book to the Imax expedition are not referring to the IMAX Corporation or indeed to IWERKS Entertainment, Inc.

Where this book quotes directly from other authors, there may be occasions where IMAX or IMAX/IWERKS is used to refer to the Imax expedition. This is beyond the author’s control and we apologise for this overlap in the adopted method.

Acknowledgements

There are many people I wish to thank for so generously giving their time to assist me on this personal journey over the last five years. More than anyone, I would like to thank my wife Catherine for showing such patience and understanding, as well as being the voice of reason in difficult times.

Others to whom I wish to extend my sincere gratitude include: Geoff Scarth and Olwyn Hocking for their belief in the difficult task they knew I had set myself, for their continued support and sound advice based on professional experience, which guided me along a logical path.

Dr Henrik Jessen Hansen for the considerable amount of time he has taken to respond to my numerous questions, and whose answers have helped provide an important insight into the days leading up to the tragedy of 10 May 1996.

The many meteorologists who have assisted with my investigation and without whom I would have been totally lost.

Mike Harrison, who has made countless enquiries on my behalf and who must have spent untold hours behind the scenes or at his computer answering my continual questions; for making the time, along with his colleague, to read the archives that would prove so invaluable in my research.

Søren Olufsen from the Danish Meteorological Institute, whose excellent recall opened the way for me.

Bob Aran and Martin Harris for the thoughtfulness they displayed as I tested their memories on the events of so long ago.

Joey Comeaux, Will Spangler, Leslie Forehand, Jan Carpenter and William Brown from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). David Ucko, Valentine Kass, Robert Robinson and Hyman Field (retired) from the National Science Foundation (NSF). Fiona Gedge, Marion Archer and Kate Strachan from the UK Met Office. Keith Fielding from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF). And the many other members of staff from meteorological institutions around the globe who were so helpful in assisting me with my enquiries.

Henry Todd for his generosity, patience and understanding over several Everest expeditions. Iswari Paudel for dealing with safety in the most difficult of circumstances. My fellow climbers Neil Laughton, Paul Deegan, Brigitte Muir, Nikolai Sitnikov and Crag Jones.

The other people who have helped along the way: Gladys Hayles, Michael Dunn, Ben Bradfield, Colin Westland, Hazel Morton, Peter Molnar, Harry Taylor, Ed Douglas, Lindsay Griffin, Geoff Birtles, John Traynor, Simon Manns and Roger Southcott to name but a few.

There are many more people than I have listed here. Five years is a long time. To all who helped me along my way: thank you. For without the help of so many individuals this book would have never been completed.

I would like to conclude by thanking my agent, Andrew Gordon of David Higham Associates, for showing faith in my work and for understanding that this needed to be published. To Bill Campbell of Mainstream Publishing for taking the book on, to my thoughtful and meticulous editor Ailsa Bathgate, to whom I am indebted, and Amanda Telfer for her sound advice; to Kate McLelland for the excellent graphics, and to Graeme Blaikie and all the other staff at Mainstream who have assisted with the publication of this book.

Contents

Introduction: Ascending into Turmoil

It was late afternoon on 10 May 1996. The winds on Everest’s upper reaches, which had been gradually building up over the preceding days, took a sudden turn for the worse. Descending from the summit were two guided teams. Having become dangerously spread out along Everest’s South East Ridge, they found themselves fighting for their very survival. Bolts of lightning flashed eerily in the dark clouds that had blown in with the storm; thunder clashed terrifyingly close overhead. The wind brought with it a blizzard of driving snow that would change the landscape out of all recognition for the descending climbers, who became hopelessly lost in near white-out conditions.

Meanwhile, the team I was with was climbing up from Camp 3 on the Lhotse Face to Everest’s South Col, from where we planned to launch our own summit bid later that same evening. During this upward move, we were sheltered from the winds. The light overhead disappeared into swirling misty cloud; there was a sense of foreboding in the air. It was only when I emerged out of the lee and onto this desolate rocky plateau, just as darkness was settling over the mountain, that I was struck by the rising storm. I bowed my head against the relentless onslaught of the horizontal blizzard ripping across from Tibet.

Totally unaware of the struggle for survival of the two guided teams, I dived into our tent to join my fellow climbers. They were preparing to settle down for the night. We now knew fine well there would be no summit bid that night and questioned what we were doing there in the first place in such conditions.

We had no clue that by the following day five people would be dead, others close to death itself. One, a diminutive Japanese lady, lay 150 yards from our tent, across the flat expanse of the South Col. As shocked awareness dawned, we could not understand why no one had told us what was happening outside our tent or asked us for help.

But more than this, I had been wrestling with a nagging doubt. During the climb, I had questioned over the radio the decision to go; I felt it had been obvious that the conditions were not settled enough.

There were many questions that plagued me, but immediately afterwards was not the time to ask. I returned home that year and re-entered my normal life, and in the end the questions were never addressed. I even avoided all the books and accounts that followed . . . that was until 2004.

Finally, I was compelled for my own peace of mind to search for an understanding of the events that had led to the deaths of eight people on Everest that night. I turned to published accounts, some of which had become international bestsellers, and to the films that had been made in the intervening time. I hoped that I might find the answers I was looking for, but that was not to be the case. Instead, they only served to raise more questions in my mind. And so began my personal journey, one that would span the next five years.

It was only once I had uncovered the staggering, and hitherto unpublished, circumstances that had led to Everest’s worst-ever disaster that I could truly come to terms with what happened that fateful day.

The Meaning of Life

Hanging in the garage was the motorcycle petrol tank I had painted emperor purple. The year was 1970 and it was my 15th birthday. I’d bought myself the 200cc Triumph tiger cub for the princely sum of £5. The engine didn’t run, but I wasn’t bothered. How it was going to look was all-important. I wouldn’t be able to ride it on public roads for another year anyway, not until I turned 16.

I shut the garage door to stop dust landing on the lovingly applied paint and grasped the small gold-coloured carton deep in my trouser pocket. It was a pack of ten Benson and Hedges Sovereign cigarettes. I’d bought them because the friends I hung around with had started to smoke. The choice of brand had been made because gold looked more sophisticated to me than the mundane colours of other makes displayed in the newsagent shop.

My parents didn’t smoke, and I’d had to find a place where the smell would not be detected. In recent weeks, I had located the perfect spot. Rushing up the winding staircase of our large three-storey Edwardian house, I made my way to the attic rooms. Next to my bedroom was the playroom, with two large windows separated by a column of brick. I looked out at the narrow lead-lined veranda enclosed by an ornate wrought-iron balustrade. This was not my chosen place. The veranda was at the front of the building, and I knew I could be seen from the street, three floors below. But it was my route to a safe hiding place. Through a daredevil antic, I had discovered that if I climbed over the left-hand side of the balustrade and stood on the four-inch-wide sandstone edge, I could launch myself up the smooth slate roof. With a hard push off, the crepe soles of my shoes and the palms of my hands gave me enough grip, provided I was quick, to reach the top of the attic’s large dormer window.

Other books

Sheepfarmers Daughter by Moon, Elizabeth

Romance of a Lifetime by Carole Mortimer

The Chimney Sweeper's Boy by Barbara Vine

Mark of the Witch (Boston Witches) by Jessica Gibson

Stories I Only Tell My Friends: An Autobiography by Rob Lowe

Rising by Kassanna

Fractured Memory by Jordyn Redwood

Home Ice by Katie Kenyhercz

Ishmael Toffee by Smith, Roger

Don't Put Me In, Coach by Mark Titus