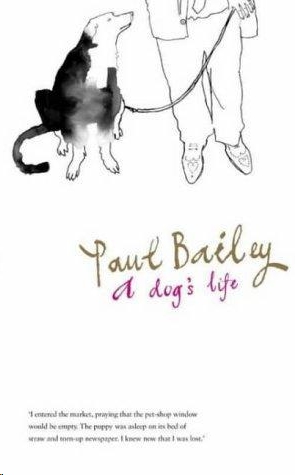

A Dog's Life

Authors: Paul Bailey

A Dog’s Life

PAUL BAILEY

HAMISH HAMILTON

an imprint of

PENGUIN BOOKS

HAMISH HAMILTON

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London

WC2R 0RL

, England

Penguin Putnam Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

M

4

V

3

B

2

Penguin Books India (P) Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi – 110 017, India

Penguin Books (NZ) Ltd, Cnr Rosedale and Airborne Roads, Albany, Auckland, New Zealand

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London

WC2R 0RL

, England

First published 2003

1

Copyright © Paul Bailey, 2003

Illustrations © Alice Tait, 2003

Photograph on p ii © Jane Brown, 2003

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Excerpt from ‘Song for the Rainy Season’ from

The Complete Poems 1927–1979

by Elizabeth Bishop.

Copyright © 1979, 1983 by Alice Helen Methfesee. Reprinted by permission of Farrar, Strous and Giroux,

LLC. Excerpt from

Step Inside Love

by Lennon and McCartney. Reprinted by permission of Sony/ATV

Music Publishing. Poem and excerpt by Geoffrey Grigson. Reprinted by permission of David Higham

Associates Limited.

All rights reserved.

Without limiting the rights under copyright

reserved above, no part of this publication may be

reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system,

or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior

written permission of both the copyright owner and

the above publisher of this book

EISBN: 978–0–141–90145–9

For Deborah Rogers, with love and gratitude

I should like to express my gratitude to Jeremy Trevathan for suggesting that I write about Circe. I also wish to thank Jane Gregory for her stimulating company in the park, and Michael Gordon, the vet who cared for Circe throughout her life. My salutations to the ever-patient Tony Lacey and to the incomparable Zelda Turner.

Early one evening in September 1990, I picked up the telephone and dialled a familiar number. The time was five past six. A couple of minutes later, I realized why I was getting no response. The friend I was calling had been dead since March.

I put down the phone and sat in silence for a while. My action had been happily automatic, I understood with dismay. I had forgotten, in my eagerness to communicate with her, that her sufferings were over and that she was lying in the same grave as the man she loved, in a quiet country churchyard. She was at rest and I, it seemed, was the perturbed spirit.

I had been living alone since the death of my long-term companion in 1986. Except that I wasn’t on my own, in reality, because I had a dog for company. I had acquired her the previous year, in peculiar circumstances that are related in this collection of memories and musings. She enslaved me from the very first moment of seeing her, and as the months went by I began to wonder if I was starting to emulate J. R. Ackerley, that famous late convert to canine charm. I remembered that the poet William Plomer, a close friend of Ackerley and E. M. Forster, had told me how ‘that bloody dog’ had taken possession of Joe to such an extent that he and Forster were loath to visit the flat in Putney Ackerley shared with his adored Queenie. (Queenie is ‘Evie’ in the novel

We Think the World of You

, and ‘Tulip’ in the memoir

My Dog Tulip

– the curious little gems he wrote towards the end of his life.) Would my own friends and acquaintances hesitate before coming to see me for fear of being nipped and barked at by the tireless Circe? I hoped not, though some of them found the business of diverting her a bore, and occasionally said so.

But Circe was not like Queenie in any respect other than beauty. Joe had recognized a kindred, wounded spirit in the bitch he rescued from his lover’s unthinking, working-class parents, whose idea of exercise was to let the creature out in the back yard, which was the size of the proverbial postage stamp. (Some neighbours of mine, the Patels, emigrants from Idi Amin’s Uganda, kept an Alsatian to protect their newspaper and tobacco shop. They had been advised that an unexercised dog would be more ferocious at warding off intruders and burglars than a healthy, contented one. The unnaturally obese animal escaped when the Patels’ children forgot to close the door behind the counter. The dog, sensing freedom, leapt over the display of sweets and chocolate bars, and dashed out of the shop. He must have run for miles, because he was never traced in west London.) Ackerley, like me, had been indifferent to dogs for most of his life. But the sight of the disconsolate, whimpering Queenie, and the feelings of outrage and pity it invoked, was to afford him an inseparable, loving relationship of a kind he had been unable to sustain with a succession of ‘ideal’ youths. Their relationship was so close, in fact, that Queenie’s jealousy of Joe’s friends became uncontainable.

Circe had known neither cruelty nor negligence when I chanced upon her in 1985. I had no cause to rescue her. It was clear from the outset that she would not be jealous of the people I knew, whom she invariably greeted with a welcoming bark and a briskly wagging tail. She was a flirt until the end of her days, never happier than when a gentle hand was stroking her tummy. Bitches have an embarrassing habit of attaching themselves to human legs in ways that appear sexually provocative, and Circe was just such a bitch. She showed a certain discrimination in her choice of leg, however, giving me reason to wonder why X’s was preferable to Y’s. Her chosen victim would laugh nervously, or blush from the shock of her abandoned advances, or call her a shameless tart while attempting to extricate himself from her passionate clutch.

Strangers, beguiled by the dog at my side, stopped to talk to her and, sometimes, to me. The strangest of these lonely, garrulous folk was Marjorie, who lived nearby with a bedraggled black mongrel, ignored by Circe, and a changing selection of cats. I could never quite place her accent, with its faint hint of Eastern Europe. Marjorie’s chatter was concerned with the injustices meted out to the likes of us by Those in Authority. As she grew angrier, she tossed her head back and I was granted a view of her snarling, discoloured teeth. Animals, bless them, were better than human beings, she maintained, and much more trustworthy. I nodded agreement.

Following the death of my companion, David, Marjorie felt compelled to offer me sympathy and commiseration. Except that she had our names confused, in spite of my quiet and firm efforts to correct her. ‘You must be missing Paul, David,’ she’d say, and I would respond ‘I’m Paul. It’s David who’s dead.’ Our meetings turned into a tiny comedy for me, thanks to her inevitable ‘Paul’s in heaven, bless him’ and ‘Paul’s happier out of it’ and ‘You look happy today, David, like the cat who’s got the cream’ and an uncountable number of similar remarks.

She continued to address me as David, and I gave up insisting on my identity. Five years after the real David’s death, I wrote a poem about my dual existence. I gave it the title ‘After-Life’:

Marjorie thinks I’m you, not me.

She calls me by your name. I’ve stopped

Correcting her. Some might say

I’ve given up the ghost.

Marjorie knows that one of us is dead.

She asks how long it is since I passed on.

‘Five years,’ I answer. She tells me I’m

At rest now, with the saints and angels.

Marjorie dotes on animals. She believes

They’re silent witnesses for God, spying

On our behaviour. Their once-dumb tongues

Speak in that heaven I’ve gone to.

Marjorie’s mad. Marjorie smells. Marjorie’s

Best avoided. I only meet her when

I’m turning corners. Then I hear

You’re looking well, considering; and young.

Marjorie moved out of the district, though she appears occasionally – dogless now – to do a little shopping and chat to old acquaintances. She walks with a stick, and is shabbier than ever, her hair like an unruly bird’s nest. I was on my way to Hammersmith Hospital on a November afternoon in 2002 when I saw a familiar figure in a tatty overcoat shuffling towards me. ‘Hullo, David,’ I heard. I was not myself again, for the first time in ages. I told her where I was heading, and that I had to keep an appointment with the chief cardiologist. She suddenly clutched my arm with her free hand. ‘Don’t go there,’ she advised. ‘They’ll murder you in there, like they tried to murder me. I wouldn’t go there, David. Be very careful. I want to die when God sees fit, not when they do.’

I freed myself from her grip, insisting that I didn’t want to be late.

‘Take my advice, David. Be careful. Your heart belongs to you, not them.’

‘After-Life’ was published in

The Times Literary Supplement

in September 1991. Some weeks later, in Rome, I was flicking through

La Repubblica

when I noticed my name and two lines from the poem. The author of the piece seemed to think that I’m a devout Roman Catholic and a devotee of St Francis of Assisi. Marjorie’s belief that animals are ‘silent witnesses for God, spying/On our behaviour’ was now attributed to me. I was Paul, to be sure, but I was also Marjorie, the scruffy mystic.

*

Thanks to Circe, I made the acquaintance of Jane Gregory and her dog, a pretty piebald mongrel named Liquorice. She and Liquorice became best friends, but they occasionally fell out with each other, as best friends do. It was wonderful to watch Liquorice bounding across the grass to greet her, and delightful to see them swimming together in the small pond in the Conservation Area of Ravenscourt Park. They would flop into the sometimes stagnant water when the heat was too much for them, emerging sodden and dripping. Jane and I backed away as they vigorously shook themselves dry.