A Just and Lasting Peace: A Documentary History of Reconstruction (50 page)

Read A Just and Lasting Peace: A Documentary History of Reconstruction Online

Authors: John David Smith

Tags: #Fiction, #Classics

Previous to this a white man undertook to do violence to the person of a negro girl

at a public place

. She was defended by her brother, when the white man took his revolver and shot him dead instantly. In this case the white man left the county, fearing the rage of the negroes, and also the interference of the Freedmen's Bureau, which was then in operation. Quite a number of colored persons have been taken from the officers of justice in this county, by a mob of white men and

put to death

. In two cases they were taken from the jail in Apling, and in one while on their way to the prison. I learned the particulars of one of these cases from the jailer himself, who was called out of his house at midnight, and forced to deliver up the keys of the jail to the mob, who took the prisoner, and hung him from a bridge near the town. This was the same Apling where the author came so near sharing the same fate.

I give the particulars of the other case, as given me by Aunt Rinah Hill, who has lived on my place several years, and is a woman of veracity. She says, that in the summer of 1869, a little child belonging to R. R., ten or twelve miles from here, bit off the finger of a colored child on the place, whose mother was named Minty. She ran after the white child, without reflecting upon the criminality of a black person pursuing a white one, and meant as she said, “merely to slap it on its ear.” The child's father, seeing the black woman pursuing his child, rushed upon her and beat her tremendously with a large white oak stick. This of course roused the ire of Berry, the colored woman's husband, and he attempted to interfere, when the oppressed victim of “imperialism” and “centralization,” exercised his “natural right” to shoot a black man, and fired at Berry, wounding him in the thigh. Berry fled to Augusta, and on his way passed by our place, and Aunt Rinah gave him a drink of water. The next day he returned guarded by two men in a buggy before him, and the same behind him, and with another at his side a horseback. The next news from this party was, that Berry and his wife, after having been lodged in jail at Apling, were taken out by

a mob and hung

; and it was reported that the heart of the man was cut out and given to the dogs. So great is the horror of the colored people of Apling jail, that some of them declare they never will be taken there alive, and one of them not long since, when on his way for an alleged theft, undertook to escape from the constable, who shot him through his body, without the least compunction.

I cannot begin to recall the instances, of maimed and wounded men, who have come to me with the story of their wrongs. Some with great gashes cut in their heads, some with wounds in their bodies, and others with mangled and shattered arms; to all of which, I have been under the sad necessity of saying, “I can do nothing for you, except to call upon the United States government to protect you;” which seemed to them, almost a mockery of their woes.

It is not for me to say who is to blame, for this failure of the government to protect its citizens. It is, perhaps, inherent in the nature of the government itself, and can only be remedied by a radical change in our governmental theory. No true man can cry out against “centralization,” when without it, there never

can

be, any safety for “the black man of the South,” from “the outrages of the rebels.” We have entreated long and loud for protection; petitions have been forwarded to Congress, entreating its interference; and Gov. Bullock has exerted himself nobly, in behalf of his colored constituents; but Congress has chosen to hear the cries of the enemies of the Union, rather than those of its defenders. Some of the blame rests upon those betrayers of our cause, who, in connection with rebel democrats, have visited Washington, and poured into the ears of Congress, and of the President, such misstatements of our condition, as have led them to doubt the necessity of their interference. In the meantime, the craven, false-hearted cry of “universal amnesty,” has uttered its fearful notes, all over the land; sounding in the ears of the terror-stricken Southern Unionist, as dismally as the yells of rejoicing, that went up from ten thousand rebel throats, when McDowell's panic-stricken squadrons, fled from the furious hosts precipitated upon them, at the unfortunate Bull Run rout. While we have been surrounded by implacable foes, thirsting for the blood of all true Union men, and have imploringly cast our eyes Northward for assistance, as the dying soldier on the battle-field, lifts his head occasionally, to see if no friendly hand can be found to wet his parched lips; those to whom we fondly looked as the embodiment of all our hopes, have sternly covered their eyes, and looked away from our imploring gaze, being dazzled by visions of future political glory; and instead of responding, “You shall be protected,” have uttered honeyed words, in dulcimer strains, that have electrified the hearts of our enemies; but have sent a mournful sound, like that of retreating squadrons, into our ears, filling us with blank dismay, and awaking in our pierced hearts, the most melancholy forebodings for the future.

But to return to my narrative of rebel atrocities. Lincoln county, adjoining this county, is emphatically, “the valley of the shadow of death,” for the poor colored man. Ever since I commenced residing here, have terrific stories of his abuse, in that county, reached my ears. Among the many tales of violence perpetrated there, I will simply give publicity to the following, as it is in every one's mouth. In the summer of 1868, when political excitement ran high, there were two colored men, father and son, named Roundtrees, and another colored man named Billy Tully, who were quite prominent republicans, and it therefore became necessary to sacrifice them. Accordingly, one night they were aroused from their slumbers, taken from their beds, and carried to a neighboring mill-dam. They were then offered their choice, to join the democratic club, or to walk out on that mill-dam and

be shot

. With true Spartan courage, they chose the latter fate, when they were immediately placed on the mill-dam, and given the poor privilege of jumping into the water, to escape the rebel bullets, as the Indians often allow a prisoner a chance to run for his life, while they are firing at him. They all three jumped into the water, at a given signal from these “well-disposed” and “repentant” rebel democrats, to deprive whom of political power is considered so very oppressive, and for whom we are so constantly exhorted to “kill the fatted calf.” One of the Roundtrees and Tully were shot dead, the other managed to escape by dodging in and out of the water, amid the shower of rebel bullets aimed at his devoted head. He was severely wounded, but fled to Augusta, and was for some time cared for at the “Freedmen's hospital” in that city. . . .

Imagine how it would be in New England, even, if there was no punishment for assault and battery, and then consider the extreme excitability of the southern character, and also they having been accustomed to nothing but deference from the blacks; and the enigma of their acts is easily solved. It is not because the Southern people, in their every day intercourse with the world, are any worse than other people, but it is the peculiar circumstances in which they are placed, that leads them to act so savagely. I make these remarks, because those who have seen the Southerners when not excited, cannot believe that such urbane gentlemen can conduct themselves so unseemly towards the blacks. The reader must never forget, that while many outrages are committed at the North, their perpetrators are almost always punished by law, but here this is seldom the case; and this fact constitutes the great difference between Southern and Northern society on this point. What the friends of the blacks are laboring for, is the establishment of law for their protection.

Let the broad ægis of law be lifted up in behalf of the colored man, and the ample folds of the mantle of justice be thrown around the white man, and these evils will nearly cease. When it cannot be done by our civil law, we ask for the establishment of military authority, as absolutely necessary to protect both black and white.

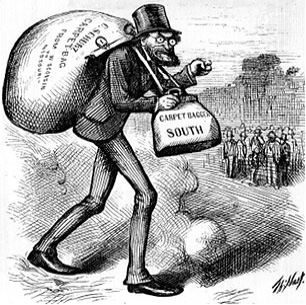

HOMAS

N

AST, “

T

HE

M

AN WITH THE (

C

ARPET)

B

AGS”

(November 9, 1872)

The renowned cartoonist Thomas Nast's wood engraving in

Harper's Weekly

appears to be a caricature of a carpetbagger, a Northerner going south to avail himself of economic and political opportunities in the defeated former Confederate states. But, no, Nast's cartoon ridiculed Missouri senator Carl Schurz, the German-American leader who had bolted the Republicans, charging Grant with political corruption and dissenting from the president's Southern policy. Schurz was a leader of the Liberal Republican party that nominated Horace Greeley in the presidential campaign against Grant in 1872. The cartoon's caption reads: “The Man with the (Carpet) Bags. The Bag in front of him, filled with others' faults, he always sees. The one behind him, filled with his own faults, he never sees.” Grant easily defeated Greeley 286 to 66 electoral votes and by a popular majority of 763,000 votes.

AMES

S

.

P

IKE,

T

HE

P

ROSTRATE

S

TATE

(1874)

Like Stearns, James Shepherd Pike (1811â1882) was a Northern newspaperman, a vocal abolitionist, and a Republican who came south during Reconstruction. He served as President Lincoln's minister to the Netherlands during the Civil War. Unlike Stearns, however, Pike opposed slavery because of his extreme antipathy toward blacks and, accordingly, condemned the role of African-Americans in Reconstruction. His

The Prostrate State

summarized Pike's observations of blacks and Republican government in South Carolina, where, during Radical Reconstruction, blacks held a majority of the elected federal and state offices. Underscoring what he considered blacks' incapacity for self-government, Pike described blacks in the crudest stereotypes of his day and warned of the Palmetto State's “Africanization.”

. . . One of the things that first strike a casual observer in this negro assembly is the fluency of debate, if the endless chatter that goes on there can be dignified with this term. The leading topics of discussion are all well understood by the members, as they are of a practical character, and appeal directly to the personal interests of every legislator, as well as to those of his constituents. When an appropriation bill is up to raise money to catch and punish the Ku-klux, they know exactly what it means. They feel it in their bones. So, too, with educational measures. The free school comes right home to them; then the business of arming and drilling the black militia. They are eager on this point. Sambo can talk on these topics and those of a kindred character, and their endless ramifications, day in and day out. There is no end to his gush and babble. The intellectual level is that of a bevy of fresh converts at a negro camp-meeting. Of course this kind of talk can be extended indefinitely. It is the doggerel of debate, and not beyond the reach of the lowest parts. Then the negro is imitative in the extreme. He can copy like a parrot or a monkey, and he is always ready for a trial of his skill. He believes he can do any thing, and never loses a chance to try, and is just as ready to be laughed at for his failure as applauded for his success. He is more vivacious than the white, and, being more volatile and good-natured, he is correspondingly more irrepressible. His misuse of language in his imitations is at times ludicrous beyond measure. He notoriously loves a joke or an anecdote, and will burst into a broad guffaw on the smallest provocation. He breaks out into an incoherent harangue on the floor just as easily, and being without practice, discipline, or experience, and wholly oblivious of Lindley Murray, or any other restraint on composition, he will go on repeating himself, dancing as it were to the music of his own voice, forever. He will speak half a dozen times on one question, and every time say the same things without knowing it. He answers completely to the description of a stupid speaker in Parliament, given by Lord Derby on one occasion. It was said of him that he did not know what he was going to say when he got up; he did not know what he was saying while he was speaking, and he did not know what he had said when he sat down.

But the old stagers admit that the colored brethren have a wonderful aptness at legislative proceedings. They are “quick as lightning” at detecting points of order, and they certainly make incessant and extraordinary use of their knowledge. No one is allowed to talk five minutes without interruption, and one interruption is the signal for another and another, until the original speaker is smothered under an avalanche of them. Forty questions of privilege will be raised in a day. At times, nothing goes on but alternating questions of order and of privilege. The inefficient colored friend who sits in the Speaker's chair cannot suppress this extraordinary element of the debate. Some of the blackest members exhibit a pertinacity of intrusion in raising these points of order and questions of privilege that few white men can equal. Their struggles to get the floor, their bellowings and physical contortions, baffle description. The Speaker's hammer plays a perpetual tattoo all to no purpose. The talking and the interruptions from all quarters go on with the utmost license. Every one esteems himself as good as his neighbor, and puts in his oar, apparently as often for love of riot and confusion as for any thing else. It is easy to imagine what are his ideas of propriety and dignity among a crowd of his own color, and these are illustrated without reserve. The Speaker orders a member whom he has discovered to be particularly unruly to take his seat. The member obeys, and with the same motion that he sits down, throws his feet on to his desk, hiding himself from the Speaker by the soles of his boots. In an instant he appears again on the floor. After a few experiences of this sort, the Speaker threatens, in a laugh, to call “the gemman” to order. This is considered a capital joke, and a guffaw follows. The laugh goes round, and then the peanuts are cracked and munched faster than ever; one hand being employed in fortifying the inner man with this nutriment of universal use, while the other enforces the views of the orator. This laughing propensity of the sable crowd is a great cause of disorder. They laugh as hens cackleâone begins and all follow.

But underneath all this shocking burlesque upon legislative proceedings, we must not forget that there is something very real to this uncouth and untutored multitude. It is not all sham, nor all burlesque. They have a genuine interest and a genuine earnestness in the business of the assembly which we are bound to recognize and respect, unless we would be accounted shallow critics. They have an earnest purpose, born of a conviction that their position and condition are not fully assured, which lends a sort of dignity to their proceedings. The barbarous, animated jargon in which they so often indulge is on occasion seen to be so transparently sincere and weighty in their own minds that sympathy supplants disgust. The whole thing is a wonderful novelty to them as well as to observers. Seven years ago these men were raising corn and cotton under the whip of the overseer. To-day they are raising points of order and questions of privilege. They find they can raise one as well as the other. They prefer the latter. It is easier, and better paid. Then, it is the evidence of an accomplished result. It means escape and defense from old oppressors. It means liberty. It means the destruction of prison-walls only too real to them. It is the sunshine of their lives. It is their day of jubilee. It is their long-promised vision of the Lord God Almighty.

Shall we, then, be too critical over the spectacle? Perhaps we might more wisely wonder that they can do so well in so short a time. The barbarians overran Rome. The dark ages followed. But then the day finally broke, and civilization followed. The days were long and weary; but they came to an end at last. Now we have the printing-press, the railroad, the telegraph; and these denote an utter revolution in the affairs of mankind. Years may now accomplish what it formerly took ages to achieve. Under the new lights and influences shall not the black man speedily emerge? Who knows? We may fear, but we may hope. Nothing in our day is impossible. Take the contested supposition that South Carolina is to be Africanized. We have a Federal Union of great and growing States. It is incontestably white at the centre. We know it to possess vital powers. It is well abreast of all modern progress in ideas and improvements. Its influence is all-pervading. How can a State of the Union escape it? South Carolina alone, if left to herself, might fall into midnight darkness. Can she do it while she remains an integral part of the nation?

But will South Carolina be Africanized? That depends. Let us hear the judgment of an intelligent foreigner who has long lived in the South, and who was here when the war began. He does not believe it. White people from abroad are drifting in, bad as things are. Under freedom the blacks do not multiply as in slavery. The pickaninnies die off from want of care. Some blacks are coming in from North Carolina and Virginia, but others are going off farther South. The white young men who were growing into manhood did not seem inclined to leave their homes and migrate to foreign parts. There was an exodus after the war, but it has stopped, and many have come back. The old slave-holders still hold their lands. The negroes were poor and unable to buy, even if the land-owners would sell. This was a powerful impediment to the development of the negro into a controlling force in the State. His whole power was in his numbers. The present disproportion of four blacks to three whites in the State he believed was already decreasing. The whites seemed likely to more than hold their own, while the blacks would fall off. Cumulative voting would encourage the growth and add to the political power of the whites in the Legislature, where they were at present over-slaughed.

Then the manufacturing industry was growing in magnitude and vitality. This spread various new employments over the State, and every one became a centre to invite white immigration. This influence was already felt. Trade was increased in the towns, and this meant increase of white population. High taxes were a detriment and a drag. But the trader put them on to his goods, and the manufacturer on to his products, and made the consumer pay.

But this important question cannot be dismissed in a paragraph. It requires further treatment. It involves the fortunes of the State far too deeply, and the duties of the white people and the interests of the property holder, are too intimately connected with a just decision of it, to excuse a hasty or shallow judgment. We must defer its further consideration to another occasion. It is the question which is all in all to South Carolina.