A Just Cause (16 page)

Authors: Jim; Bernard; Edgar Sieracki

David Miller, a veteran legislator whose district included several southern suburbs of Chicago, was then recognized and began to ask Currie and Durkin some clarifying questions. Miller was respected by members of both parties, and many assumed that he also was simply trying to support the resolution. But his questions seemed dissonant and disjointed; he was hesitant and unsure. The night before, Miller had been a guest on WVON radio, a popular station among Chicago's black community. The program featured a call-in format, and several of the callers expressed anger and skepticism about the upcoming impeachment. Miller took note. His district was predominantly minority populated, Miller himself was African American, and he was aware of the importance of the occasion. “The whole country was watching,” he later confided.

4

Blagojevich was popular in the black community. He attended black church services, appeared at black-sponsored events, and appointed African Americans to positions in government. The black community was important to his electoral success. The governor's personal narrative was that he had come from immigrant parents who worked in the steel mills with no advantage in life and had worked his way up, always struggling, fighting the odds, perpetually the outsider. He insisted that he was the crusader of good and truth, fighting for the people. Now he was again being opposed by the established powers, an evil cabal of greedy politicians. Blagojevich's narrative resonated within the black community, and many could identify with what he was saying. Many black people felt that Blagojevich was being railroaded by the established powers. Miller's radio appearance the night before provided him with an instant poll of black feelings. The reaction of listeners prompted some trepidation, and he felt he had “to get these things out.” He had whispered to Currie, “I'm going to ask you some questions.”

5

He posed two questions to Currie and Durkin. The first question, “Why now?,” was straightforward. The second question seemed imprecise,

somewhat curious. Speaking of the abuse of power that Lang had discussed, Miller asked, “How does that reflect in the criminal issues that Mr. Blagojevich is facing now? Does that have a bearing on this?” Currie explained that the criminal complaint “sparked the flame that led to the creation of the committee” but cited that other administrative actions such as that related to the flu vaccines along with the disregard for legislative authority, taken together with the criminal allegations, constituted justification for impeachment. Miller responded by stating that the governor had not been granted the right of due process under the US Constitution. “Haven't we circumvented it?” he asked. Currie reiterated what she had expressed many times in the impeachment hearings, that the investigative committee was not a criminal jury and that “nothing in our Constitution nor any State or Federal Constitution suggests that our standards should be a criminal one.” Currie argued that the governor “spent a lot of time figuring out how to sell state actions and state money for his political and personal benefit” and that the testimony before the committee was “not refuted.” Taken as a whole, Currie said, Blagojevich was not “fit to govern and he should be removed from office.” Miller agreed and said that the points made by the investigative committee, taken by themselves, did not constitute grounds for impeachment, but taken as a whole, “collectively,” they represented “a slow train wreck moving that has all sort of accumulated to our actions that will be today.” Currie agreed that Miller's analogy was “exactly the way to think about it” (27â29).

6

Wishing to conclude his questions, Miller began to make a statement on the “matter at hand today,” but Durkin sought recognition. The former Cook County prosecutor was aware of the importance of the moment. He knew that everything he said and everything the house did would be analyzed and dissected, and he knew the world press was watching. He wanted to expand on Currie's remarks. Miller had asked “a few questions,” he said, and he wanted to add clarification. Addressing the “why now” question, he explained that the governor's criminal allegations might take two to three years to be settled in federal court. In the meantime, the governor could still make appointments and sign laws and would have all the rights and authority he had under the statutes and the Constitution. Durkin stated that the impeachment process was “strictly a legislative process.” He also reiterated that although the state Constitution does not provide for due process in the impeachment process, the investigative committee had afforded the governor “due process plus.” Durkin said that a federal agent had

signed and sworn an affidavit attesting to the accuracy of the recordings of the governor, and a federal judge had authorized the wiretaps contained in the criminal complaint. The committee had weighed the evidence carefully and paid particular attention to the affidavit concerning the wiretaps, he said, because the governor's attorney Edward Genson “went to great length . . . to challenge the integrity of that document.” Due process was afforded, Durkin said, but the governor and his attorney did not avail themselves of it. “That's their decision,” he said. Durkin then answered Miller's first question by saying, “Because I think we have to right now” (29â30). Durkin's comments provided the rationaleâthe political coverâmany needed to vote for impeachment.

Miller said that he agreed with the committee's report and that as a member of JCAR, he had voted to reject the governor's health expansion program “time and time again.” “The end doesn't justify the means,” he said, and it was his responsibility as an elected official to work with others to “lobby Members on both sides of the aisles, in both chambers to hopefully agree upon things that I feel that is [of] value to my community and the State of Illinois.” Miller then called for support of the impeachment (31).

Discussion of most important issues brought up before the Illinois General Assembly is generally accompanied by a degree of political posturing, with for-the-record speeches that establish positions for constituent consumption or are intended for use in future press releases, but on the occasion of this momentous resolution, the political rhetoric and bombast were limited. Tom Cross and Jim Durkin were the only Republicans to speak, and the other random speakers on this issue limited themselves to a few brief remarks.

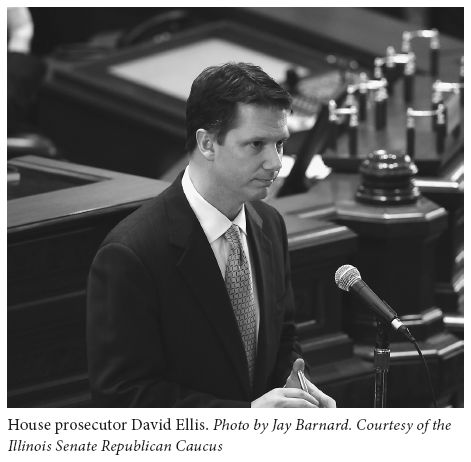

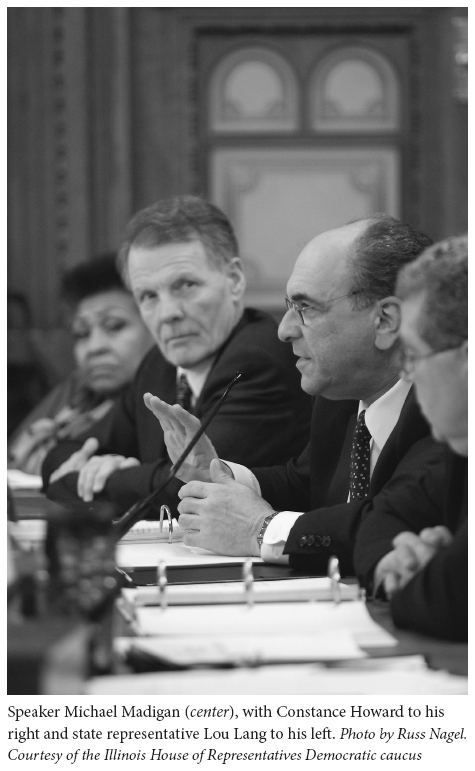

Barbara Currie delivered brief closing remarks. She declared, “This Governor has violated his oath of office. This Governor has breached the public trust. This Governor must be impeached.” The house did not need to hear anything further. Most were deeply saddened by what was about to take place. Speaker Madigan then posed the question: “Shall the House adopt House Resolution 1671?” (44). The tally was 114 voting yes, 1 voting no. Before the vote, Madigan had asked Ellis how he should announce the results. Ellis told him to simply say that the governor was impeached.

7

Now the Speaker announced the vote: “The House does adopt House Resolution 1671 and Governor Blagojevich is hereby impeached” (44).

The results did not immediately register with all observers, perhaps because the house announces thousands of vote results in the course of

a session in the same staccato cadence with which the results of HR 1671 were officially announced. But in a few moments the magnitude of what had just happened became clear, and the legislators slowly left the house floor. It was the first time in the state's history that the house had voted to impeach a governor. There were no cheers among the members or in the galleries. Those present did not feel joy, just relief, sadness, and regret.

8