A Little History of the World (14 page)

Read A Little History of the World Online

Authors: E. H. Gombrich,Clifford Harper

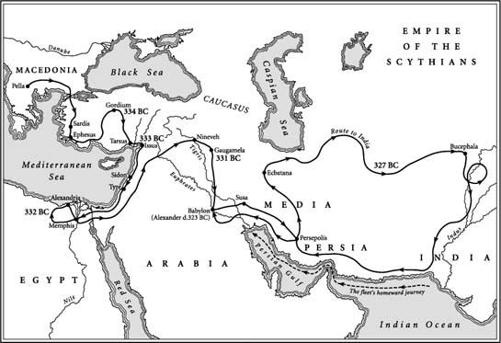

Alexander punished the assassins. Now he was king of the whole of Persia. Greece, Egypt, Phoenicia, Palestine, Babylonia, Assyria, Asia Minor and Persia – all these were now part of his empire. He set about putting it in order. His commands could now be said to reach all the way from the Nile to Samarkand.

This would probably have been enough for you or me, but Alexander was far from satisfied. He wanted to rule over new, undiscovered lands. He longed to see the mysterious, far-off peoples merchants talked about when they came to Persia with rare goods from the East. Like Dionysus in the Greek legend, he wanted to ride in triumph to the sun-burnished Indians of the East, and there receive their tribute. So he spent little time in the Persian capital, and in 327 BC led his army on the most perilous adventures over unknown and unexplored mountain passes and down along the valley of the Indus into India. But the Indians did not submit to him willingly. The hermits and penitents in the forests denounced the conquerors from the distant West in their sermons. And the soldiers of the warrior caste fought valiantly, so that every city had to be besieged and conquered in its turn.

Alexander himself was no less valiant, as is shown by his encounter with an Indian king. King Porus had lain in wait for him on a branch of the Indus River, with a mighty army of war elephants and foot soldiers. When Alexander reached the river the king’s army was positioned on the far bank, and Alexander and his soldiers had no choice but to cross the river in the face of the enemy host. His success was one of his greatest feats. Yet even more remarkable was his victory over that army, in the stifling heat of India. Porus was brought before him in chains. ‘What do you want of me?’ asked Alexander. ‘Only that you treat me as befits a king.’ ‘And that is all?’ ‘That is all,’ came the reply, ‘there is no more to be said.’ Alexander was so impressed that he gave Porus back his kingdom.

He himself wished to march on even further towards the east, to the even more mysterious and unknown peoples who lived in the valley of the River Ganges. But his soldiers had had enough. They didn’t want to march on to the end of the world. They wanted to go home. Alexander begged and pleaded and threatened to go on alone. He shut himself up in his tent and refused to come out for three whole days. But in the end the soldiers had their way, and he was forced to turn back.

But they did agree to one thing: they wouldn’t go home by the same route. Of course it would have been far the simplest thing to do, since those regions had already been conquered. But Alexander wanted new sights and new conquests. So they followed the Indus down as far as the sea. There he put part of his army onto ships and sent them home that way. He himself chose to endure new and terrible hardships as he marched with the rest of the army over pitiless desert wastes. Alexander bore all the privations his army endured and took no more water and slept no more than the next man. He fought in the foremost ranks.

On one occasion, he only escaped death by a miracle. That day they were besieging a fortress. Ladders had been set in place to scale the walls. Alexander was first up. He had reached the top when the ladder snapped under the weight of the soldiers behind, leaving him alone on top of the wall. His men shouted to him to jump back down. Instead he leapt straight into the city and, with his back to the ramparts, defended himself with his shield against overwhelming odds. By the time the others were able to scale the wall to rescue him, he had already been hit by an arrow. It must have been thrilling!

In the end they returned to the Persian capital. But since Alexander had burnt it down when he conquered it, he chose to set up his court in Babylon. This was no idle choice: Son of the Sun to the Egyptians, King of Kings to the Persians, with troops in India and in Athens, he was determined to show the world that he was its rightful ruler.

It may not have been pride that prompted him to do so. As a pupil of Aristotle he understood human nature and knew that power needs pomp and dignity if it wants to make the right impression. So he introduced all the age-old ceremonies of the Babylonian and Persian courts. Anyone who came into his presence had to fall on their knees before him and speak to him as if he were a god. And in the manner of Oriental kings he had several wives, among them the daughter of the Persian king, Darius, which made him that king’s rightful successor. For Alexander didn’t wish to be seen as a foreign conqueror. His aim was to combine the wisdom and splendour of the East with the clear thinking and vitality of the Greeks, and so create something entirely new and wonderful.

But this idea didn’t please the Greeks and Macedonians at all. They were the conquerors, so they should be the masters. What was more, they were free men, and used to their freedom. They weren’t going to bow down to any man on earth – or, as they put it, lick any man’s boots. His Greek friends and the soldiers became increasingly rebellious, and he was forced to send them home. Alexander never realised his great ambition of mingling the two peoples, even though he handed out rich dowries to ten thousand Macedonian and Greek soldiers so that they could marry Persian women, and laid on a great wedding feast for all.

He had great plans. He wanted to found many more cities like Alexandria. He wanted to build roads, and change the face of the world with his military campaigns, whether the Greeks liked it or not. Just imagine, in those days, to have a regular postal service running from India to Athens! But in the midst of all his plans he died, in Nebuchadnezzar’s summer palace, in 323 BC. He was thirty-two years old – an age when most people’s lives have barely begun.

To the question of who should succeed him, he answered, in his fever: ‘He who is most worthy.’ But there was no one. The generals and princes in his entourage were greedy, dissolute and dishonest. They fought over the empire until it fell apart. Egypt was then governed by a family of generals – the Ptolemies. The Seleucids ruled Mesopotamia, and the Attalids Asia Minor. India was simply abandoned.

Follow the arrows! They will take you in Alexander’s footsteps as he conquers half the world.

But although the empire was in pieces, Alexander’s grand project slowly went on taking shape. Greek art and the spirit of Greece had penetrated Persia and passed on through India to China. Meanwhile the Greeks themselves had learnt that there was more to the world than Athens and Sparta, and more to do than waste their lives in endless squabbling between Dorians and Ionians. And, having lost the little political power they once had, the Greeks went on to be the bearers of the greatest intellectual force there has ever been, the force we know as Greek culture. This force was protected and preserved in some very special fortresses. Can you guess what those fortresses were? They were libraries. Alexandria, for instance, had a Greek library that held around seven hundred thousand scrolls. Those seven hundred thousand scrolls were the Greek soldiers who set off to conquer the world. And that empire is still standing today.

EW

W

ARS AND

N

EW

W

ARRIORS

BC

.

The Romans had lots of other stories about the glorious past of their little city. Tales of kings, both good and bad, and their wars with neighbouring cities – I almost said with neighbouring villages. The seventh and last king was called Tarquin the Proud, and he was said to have been assassinated by a nobleman named Brutus. From that time onwards, power was in the hands of the nobility. These were the patricians – the word means something like ‘city fathers’ – although in those days they weren’t citizens as we know them, but old landowning families with vast estates of fields and meadows. And they alone had the right to choose officials to govern the city, once there were no more kings.

In Rome the highest officials were the consuls. There were always two of them ruling jointly, and they held office for just one year. Then they had to stand down. Of course, the patricians weren’t the only people who lived in the city, but if you didn’t have illustrious ancestors or great estates you weren’t noble. The others were the plebeians, and they were almost a caste of their own as in India. A plebeian couldn’t marry a patrician. Still less could he become a consul. He wasn’t even allowed to voice his opinion at the People’s Assembly on the Field of Mars outside the city gates. But the plebeians were many and every inch as strong-willed and stubborn as the patricians. Unlike the gentle Indians they didn’t willingly submit. On more than one occasion they threatened to leave the city unless they were treated better and given a share of the fields and pastures which the patricians liked to keep for themselves. After a relentless struggle which went on for more than a hundred years, the plebeians of Rome finally succeeded in obtaining the same rights as the patricians. Of the two consuls, one would be a patrician, the other a plebeian. So justice was done. The end of this long and complicated struggle coincided with the time of Alexander the Great.

From this struggle you will have gained some idea of what the Romans were like. They were not as quick-thinking or as inventive as the Athenians. Nor did they take such delight in beautiful things, in buildings, statues and poetry. Nor was reflecting on the world and on life so vital to them. But when they set out to do something, they did it, even if it took two hundred years, for they were peasants through and through, not restless seafarers like the Athenians. Their homes, their livestock and their land – these were what mattered. They cared little for travel, they founded no colonies. They loved their native city and its soil and would do anything and everything to increase its prosperity and power. They would fight for it and they would die for it. Beside their native soil there was one other thing that was important to them: their law. Not the law that is just and fair and before which all men are equal, but the law which is law. The law that is laid down. Their laws were inscribed on twelve bronze tablets set out in the marketplace. And those few, stern words meant precisely what they said. No exceptions, no compassion, no mercy. For these were the laws of their ancestors and they must be right.