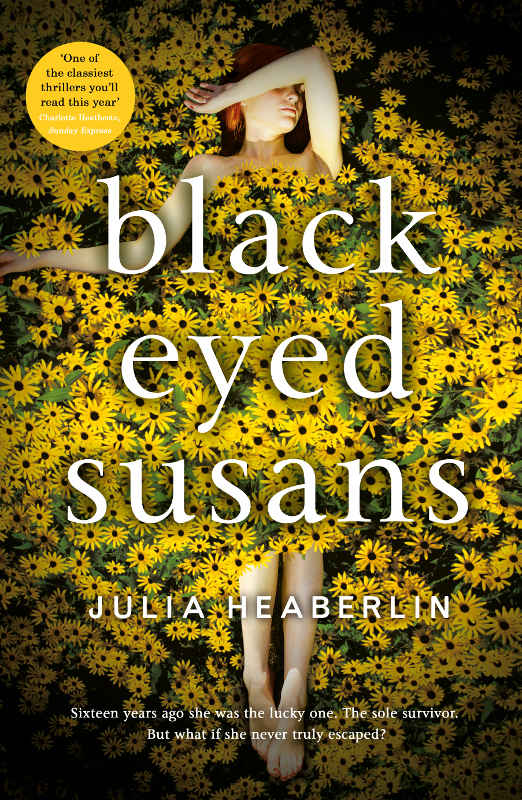

Black-Eyed Susans

Authors: Julia Heaberlin

Heaberlin

BLACK-EYED SUSANS

For Sam, my game changer

Thirty-two hours of my life are missing.

My best friend, Lydia, tells me to imagine

those hours like old clothes in the back of a dark closet. Shut my eyes. Open the door.

Move things around. Search.

The things I do remember, I’d rather

not. Four freckles. Eyes that aren’t black but blue, wide open, two inches from

mine. Insects gnawing into a smooth, soft cheek. The grit of the earth in my teeth.

Those parts, I remember.

It’s my seventeenth birthday, and the

candles on my cake are burning.

The little flames are waving at me to hurry

up. I’m thinking about the Black-Eyed Susans, lying in freezing metal drawers. How

I scrub and scrub but can’t wash away their smell no matter how many showers I

take.

Be happy.

Make a wish.

I paste on a smile, and focus. Everyone in

this room loves me and wants me home.

Hopeful for the same old Tessie.

Never let me remember.

I close my eyes and blow.

TESSA AND TESSIE

My mother she killed me,

My father he ate me,

My

sister gathered together all my bones,

Tied them in a silken handkerchief,

Laid them

beneath the juniper-tree,

Kywitt, kywitt, what a beautiful bird am I!

—Tessie, age 10, reading aloud to her grandfather

from “The Juniper Tree,” 1988

For better or worse, I am walking the crooked

path to my childhood.

The house sits topsy-turvy on the crest of a

hill, like a kid built it out of blocks and toilet paper rolls. The chimney tilts in a

comical direction, and turrets shoot off each side like missiles about to take off. I

used to sleep inside one of them on summer nights and pretend I was rocketing through

space.

More than my little brother liked, I had

climbed out one of the windows onto the tiled roof and inched my scrappy knees toward

the widow’s peak, grabbing sharp gargoyle ears and window ledges for balance. At

the top, I leaned against the curlicued railing to survey the flat, endless Texas

landscape and the stars of my kingdom. I played my piccolo to the night birds. The air

rustled my thin white cotton nightgown like I was a strange dove alit on the top of a

castle. It sounds like a fairy tale, and it was.

My grandfather made his home in this crazy

storybook house in the country, but he built it for my brother, Bobby, and me. It

wasn’t a huge place, but I still have no idea how he could afford it. He presented

each of us with a turret, a place where we could hide out from the world whenever we

wanted to sneak away. It was his grand gesture, our personal Disney World, to make up

for the fact that our mother had died.

Granny tried to get rid of

the place shortly after Granddaddy died, but the house didn’t sell till years

later, when she was lying in the ground between him and their daughter. Nobody wanted

it. It was weird, people said. Cursed. Their ugly words made it so.

After I was found, the house had been pasted

in all the papers, all over TV. The local newspapers dubbed it Grim’s Castle. I

never knew if that was a typo. Texans spell things different. For instance, we

don’t always add the

ly.

People whispered that my grandfather must

have had something to do with my disappearance, with the murder of all the Black-Eyed

Susans, because of his freaky house.

“Shades of Michael Jackson and his

Neverland Ranch,”

they muttered, even after the state sent a man to Death

Row a little over a year later for the crimes. These were the same people who had driven

up to the front door every Christmas so their kids could gawk at the lit-up gingerbread

house and grab a candy cane from the basket on the front porch.

I press the bell. It no longer plays

Ride of the Valkyries.

I don’t know what to expect, so I am a little

surprised when the older couple that open the door look perfectly suited to living here.

The plump worn-down hausfrau with the kerchief on her head, the sharp nose, and the dust

rag in her hand reminds me of the old woman in the shoe.

I stutter out my request. There’s an

immediate glint of recognition by the woman, a slight softening of her mouth. She

locates the small crescent-moon scar under my eye. The woman’s eyes say

poor

little girl,

even though it’s been eighteen years, and I now have a girl

of my own.

“I’m Bessie Wermuth,” she

says. “And this is my husband, Herb. Come in, dear.” Herb is scowling and

leaning on his cane. Suspicious, I can tell. I don’t blame him. I am a stranger,

even though he knows exactly who I am. Everyone in a five-hundred-mile radius does. I am

the Cartwright girl, dumped once upon a time with a strangled college student and a

stack of human bones out past Highway 10, in an abandoned patch of field near the

Jenkins property.

I am the star of screaming

tabloid headlines and campfire ghost stories.

I am one of the four Black-Eyed Susans. The

lucky

one.

It will only take a few minutes,

I

promise. Mr. Wermuth frowns, but Mrs. Wermuth says,

Yes, of course.

It is clear

that she makes the decisions about all of the important things, like the height of the

grass and what to do with a redheaded, kissed-by-evil waif on their doorstep, asking to

be let in.

“We won’t be able to go down

there with you,” the man grumbles as he opens the door wider.

“Neither of us have been down there

too much since we moved in,” Mrs. Wermuth says hurriedly. “Maybe once a

year. It’s damp. And there’s a broken step. A busted hip could do either of

us in. Break one little thing at this age, and you’re at the Pearly Gates in

thirty days or less. If you don’t want to die, don’t step foot inside a

hospital after you turn sixty-five.”

As she makes this grim pronouncement, I am

frozen in the great room, flooded with memories, searching for things no longer there.

The totem pole that Bobby and I sawed and carved one summer, completely unsupervised,

with only one trip to the emergency room. Granddaddy’s painting of a tiny mouse

riding a handkerchief sailboat in a wicked, boiling ocean.

Now a Thomas Kinkade hangs in its place. The

room is home to two flowered couches and a dizzying display of knickknacks, crowded on

shelves and tucked in shadow boxes. German beer steins and candlesticks, a

Little

Women

doll set, crystal butterflies and frogs, at least fifty delicately etched

English teacups, a porcelain clown with a single black tear rolling down. All of them, I

suspect, wondering how in the hell they ended up in the same neighborhood.

The ticking is soothing. Ten antique clocks

line one wall, two with twitching cat tails keeping perfect time with each other.

I can understand why Mrs. Wermuth chose our

house. In her way, she is one of us.

“Here we go,” she says. I follow

her obediently, navigating a

passageway that snakes off the living room.

I used to be able to take its turns in the pitch dark on my roller skates. She is

flipping light switches as we go, and I suddenly feel like I am walking to the chamber

of my death.