A People's Tragedy (160 page)

Read A People's Tragedy Online

Authors: Orlando Figes

By the late summer of 1921, when much of the countryside was struck down with famine, most of the peasant revolts had been defeated in the military sense. Antonov's army was destroyed in June, although he escaped and with smaller guerrilla forces continued to make life difficult for the Soviet regime in the Tambov countryside until the following summer, when he was finally hunted down and killed by the Cheka. In western Siberia, the Don and the Kuban all but the smallest peasant bands had been destroyed by the end of July, although peasant resistance to the Soviet regime continued on a smaller scale — and in more passive ways — until 1923. As for Makhno, he gave up the struggle in August 1921 and fled with his last remaining followers to Romania, although his strongholds in the south-east Ukraine continued to be a rebellious region for several years to come. To many Ukrainians Makhno remained a folk-hero (songs were sung about him at weddings and parties even as late as the 1950s) but to others he was a bogey man. 'Batko Makhno will get you if you don't sleep,' Soviet mothers told their children.61

The Mensheviks and SRs were suppressed along with the rebels. It was axiomatic to Bolshevik propaganda that the peasant revolts and workers' strikes had been organized by these parties. It was certainly true that they had sympathized with them, and in some cases had even supported them. But much more relevant was the fact that, as the popularity of the Bolsheviks had plummeted, so that of the SRs and Mensheviks had grown: they were a threat to the regime. By claiming that the SRs and Mensheviks had organized the strikes and revolts of 1921, the Bolsheviks sought both a pretext to destroy their last political rivals and an explanation for the protests that denied their popular base. The arrest of the 'counter-revolutionary' Mensheviks, some 5,000 in all, during 1921, and the grotesque show trial of the SR leaders the following year, when the whole party was in effect convicted as 'enemies of the people',62 were last desperate measures by the Bolsheviks to claim a popular legitimacy for their bankrupt revolution.

* * * The New Economic Policy was originally conceived as a temporary retreat. 'We are making economic concessions in order to avoid political ones,' Bukharin told the Comintern in July. 'The NEP is only a temporary deviation, a tactical retreat, a clearing of the land for a new and decisive attack of labour against the front of international capitalism,' Zinoviev added in December. Lenin also saw it in these terms.

The NEP was 'a peasant Brest-Litovsk', taking one step backwards to take two steps forward. But, unlike many of the other party leaders, Lenin accepted that the period of retreat was likely to be long enough — he talked vaguely of 'not less than a decade and probably more' — to constitute not just a tactical ploy but a whole recasting of the revolution. The NEP, he reminded the party in May, was to be adopted ' "seriously and

for a long time" — we must definitely get this into our heads and remember it well, because rumours are spreading that this is a policy only in quotes, in other words a form of political trickery that is only being carried out for the moment. This is not true.'63

As Lenin saw it, the NEP was more than a temporary concession to the market in order to get the country back on its feet. It was a fundamental if rather ill-formulated effort to redefine the role of socialism in a backward peasant country where, largely as a result of his own party's

coup d'etat

in 1917, the 'bourgeois revolution' had not been completed.

Only 'in countries of developed capitalism' was it possible to make an 'immediate transition to socialism', Lenin had told the Tenth Party Congress. Soviet Russia was thus confronted with the task of 'building communism with bourgeois hands', of basing socialism on the market. Lenin of course remained full of doubts: at times he expressed fears that the regime would be drowned in a sea of petty peasant capitalism. But in the main he saw the market — regulated by the state and gradually socialized through cooperatives — as the only way to socialism. Whereas the Bolsheviks up till now had lived by the maxim 'The less market the more socialism', Lenin was moving towards the slogan 'The more market the more socialism'.64

But, like the leopard with its spots, the Bolsheviks could not easily erase their innate mistrust of private trade. Even Bukharin, who later became the main defender of the NEP, warmed to it only slowly during the course of 1921— 3. Many of the rank-and-file Bolsheviks, in particular, saw the boom in private trade as a betrayal of the revolution. What, only months ago, had been condemned as a crime against the revolution was now being endorsed and encouraged. Moreover, once the doors had been opened to the market it was difficult to stop the flood of private trade that was almost bound to follow after the shortages of the previous four years. By 1921 the whole population was living in patched-up clothes and shoes, cooking with broken kitchen utensils, drinking from cracked cups. Everyone needed something new. People set up stalls in the streets to sell or exchange their basic household goods, much as they do today in most of Russia's cities; flea-markets boomed; while 'bagging' to and from the countryside once again became a mass phenomenon. Licensed by new laws in

1921—2,

private cafes, shops and restaurants, night clubs and

THE REVOLUTIONARY INHERITANCE

96-7 The people reject the Bolsheviks.

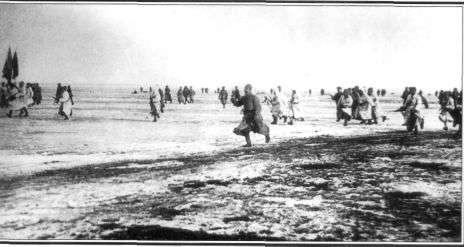

Above:

Red Army troops assault the mutinous Kronstadt Naval Base, 16 March 1921.

Below:

peasant rebels ('Greens') attack a train of requisitioned grain, February 1921.

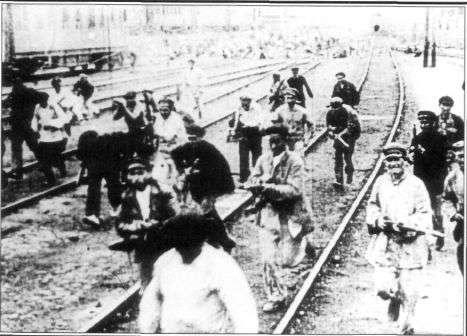

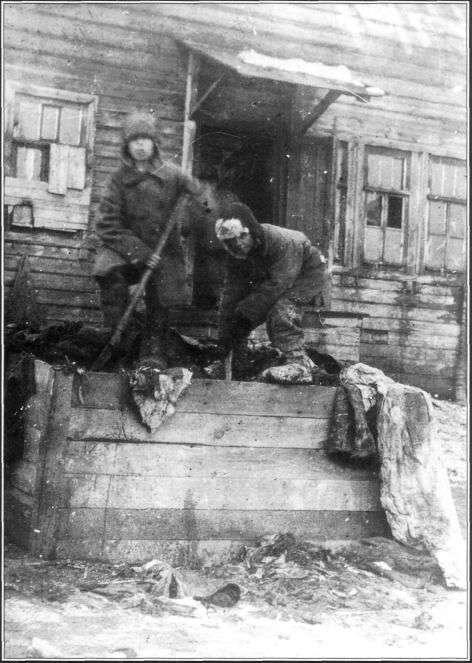

98-100 The famine crisis of 1921-2.

Above:

Bolshevik commissars inspect the harvest failure in the Volga region, 1921. The crisis was largely the result of Bolshevik over-requisitioning.

Below,

the victims of the crisis; an overcrowded cemetery in the Buzuluk district, 1921.

Opposite:

cannibals with their victims, Samara province, 1921.

101-3 Orphans of the revolution.

Above:

street orphans in Saratov hunt for food remains in a rubbish tip, 1921.

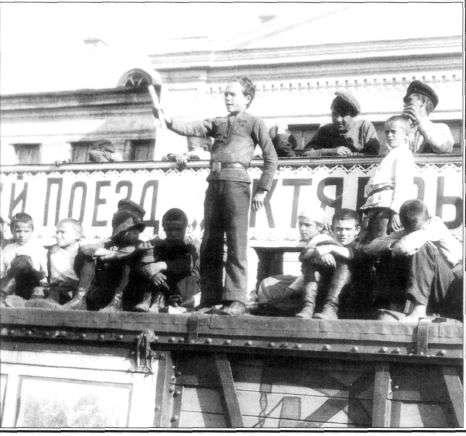

Opposite above:

orphans were ripe for political indoctrination.

This young boy, seen here giving a speech from the agit-train

October Revolution,

was the Secretary of the Tula Komsomol. He was part of the generation which, a decade later, pioneered the Stalinist assault on old Russia.

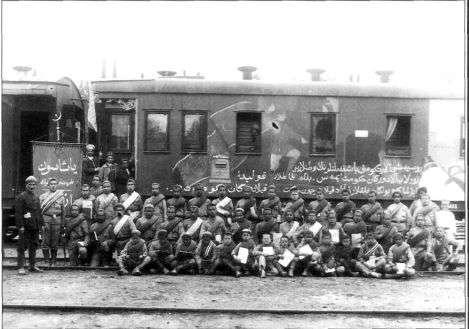

Opposite below:

orphans also made good soldiers: a national unit of the Red Army in Turkestan, 1920.