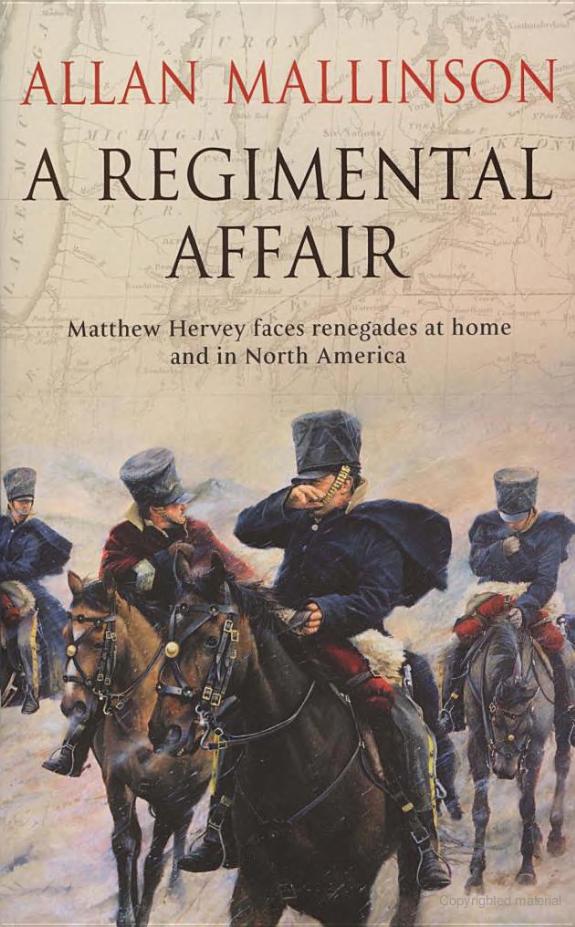

A Regimental Affair

Read A Regimental Affair Online

Authors: Allan Mallinson

ALLAN MALLINSON

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Version 1.0

Epub ISBN 9781407057422

TRANSWORLD PUBLISHERS

61–63 Uxbridge Road, London W5 5SA

a division of The Random House Group Ltd

RANDOM HOUSE AUSTRALIA (PTY) LTD

20 Alfred Street, Milsons Point, Sydney,

New South Wales 2061, Australia

RANDOM HOUSE NEW ZEALAND

18 Poland Road, Glenfield, Auckland 10, New Zealand

RANDOM HOUSE SOUTH AFRICA (PTY) LTD

Endulini, 5a Jubilee Road, Parktown 2193, South Africa

Published 2001 by Bantam Press

a division of Transworld Publishers

Copyright © Allan Mallinson 2001

The right of Allan Mallinson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 0593 043758

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers.

Typeset in 11/13pt Times by Falcon Oast Graphic Art

Printed in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc, Bungay, Suffolk 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

To

The late Colonel George Stephen,

sometime commanding officer 13th/18th Royal Hussars

(Queen Mary’s Own) and, ‘from time to time in such other regiments

and corps as Her Majesty directs’, a Cameronian and a Grey.

‘What a Go!’

Also by Allan Mallinson

A CLOSE RUN THING

THE NIZAM’S DAUGHTERS

‘Soldiers in peace are like chimneys in summer,’ wrote William Cecil, Lord Burghley. At the end of every war, a grateful British nation has dismissed its surplus soldiers, and usually with indifference. One has only to look back not ten years, to the end of the Cold War, to see how ill-used a soldier can be when his arms are no longer required. Invariably, too, the calculation proves wrong and a shortage of soldiers soon follows – as was the case with the 1992 reductions.

After Waterloo there was a wholesale disbanding of regiments. Unlike 1992, however, when the cavalry – or, more properly, the Royal Armoured Corps – was all but eviscerated, the Duke of Wellington’s horsed regiments escaped the worst for a time because they were needed to deal with civil disturbances at home, there being no proper police force. On the whole they found it disagreeable work, as soldiers still do. One of the reasons was that their legal position was often ambiguous. I commend two books on this fascinating subject to those who would read more. First is

Military Intervention in Democratic Societies

(Croom Helm, 1985), a scholarly collection of essays edited by Peter Rowe and Christopher Whelan. Second is

Military Intervention in Britain, from the Gordon Riots to the Gibraltar Incident

(Routledge, 1990). Its author, Anthony Babington, is a retired circuit judge with

wartime military service, and it is a most authoritative and lively account of the soldier’s tribulations in aid of the civil power.

I am indebted to the staff of the Prince Consort’s Library at Aldershot, who have been most generous in searching out books and material. Again I owe many thanks to the two retired officers who keep the Small Arms Collection at the School of Infantry in Warminster, Lieutenant-Colonel ‘Tug’ Wilson and Major John Oldfield. I gratefully acknowledge, as before, my wife’s equestrian advice, and now my younger daughter’s help with the early manuscript. Fortune continues to smile on me with editors, too, for after Ursula Mackenzie’s leaving Transworld for greater things, my publishers took on strength Selina Walker, a woman of such apt cavalry credentials that the departure of Ursula (who taught me a great deal) was in the end bearable. And Simon Thorogood persists in his patient, painstaking way to serve the manuscripts and me admirably.

While I was writing this book, the man who gave my military life the greatest turn, and without whom Matthew Hervey would therefore never have been, died prematurely. I dedicate

A Regimental Affair

to him, with thankfulness and fond memories.

At the commencement of the present reign, and indeed thirty or forty years ago, peace officers were seen keeping order among the crowd, but now not a court-day passes without a strong military force being stationed on the public highway.

Henry Brougham MP,

future Whig Lord Chancellor

I found myself obliged, by every tie of duty and affection to my people, to suppress in every part those rebellious insurrections and to provide for the public safety by the most effectual and immediate application of the force entrusted to me by Parliament.

His Majesty King George III,

Debate on the King’s Speech from the Throne, Parliament,

June 1780

THE BREVET

THE PRIVILEGE OF RANK

The Horse Guards, 12 March 1817

Five major generals – so much scarlet and gold that the usually sombre meeting room of the commander-in-chief’s headquarters was for once a place of colour – sat in comfortable upholstered chairs at a long baize-covered table, their chairman, Sir Loftus Wake, Bart., the Vice Adjutant General, at the head, while on upright chairs at the wall perched the Duke of York’s military secretary and two clerks. The atmosphere was somnolent despite the morning hour. In front of each general officer lay a blue vellum portfolio tied with red silk, as well as paper, pencils and a coffee cup of delicate pink Rockingham, rather out of place. Some of the cups were empty, and were being attended to by a footman in court livery. Major-General the Lord Dunseath, a dyspeptic-looking man with a purple nose, waved him aside without a word, intent on some detail in his copy of

The Times

. The footman next proffered his coffee pot to Sir Archibald Barret, KG, a kind-faced man in spite of his eyepatch, who merely sighed and declined with the same breath. Major-General the Earl of Rotheram, noble-browed, a picture of decency, lit a cigar instead, but Sir Francis

Evans, Kt, crabbed and lacking any appreciable chin, with an ear that was turned forward like a tailor’s tab, accepted more of the strong araba and took out his snuffbox. The footman hesitated by the next, empty, chair and then moved to replenish Sir Loftus’s cup.