A Sailor's History of the U.S. Navy (23 page)

Read A Sailor's History of the U.S. Navy Online

Authors: Thomas J. Cutler

Thwarted from their mission for nearly two weeks by a ferocious storm, the crew endured the severe hardships of terrible overcrowding, spoiled food, and the exhaustion of battling mountainous waves and the continuous manning of the pumps to keep the ship from foundering. Rats and other vermin added to the hardships and made it a most miserable time.

Finally, the winds abated and the seas calmed. Exhausted by their ordeal but as determined as ever, most of

Intrepid

's crew hid themselves below decks as Catalano steered the little vessel for Tripoli's harbor; Decatur and several others disguised as native traders remained on deck. By the time they were well into the harbor, the night had turned blissfully calm. A light breeze blew toward the shoreâideal for this part of the mission, not so good for their hoped-for escape. A crescent moon showered a thin light over the dark waters, helping them to navigate but making them more visible to their adversaries.

As they approached

Philadelphia,

they could see cannons looming ominously through her open gun ports. To be discovered at this point would be a disaster, for if the Tripolitans touched off those big guns,

Intrepid

and her crew would quickly cease to exist.

A few lanterns flickered on the frigate, and Decatur could make out several turbaned heads moving about just beyond the rail. He was relieved to see that they were not hurrying. The sound of wavelets lapping at the big ship's solid hull drifted across the water, and a slight luffing of

Intrepid

's large sail seemed much louder than it actually was.

Suddenly the wind failed them, and they drifted to a halt, still about twenty yards from the frigate, still peering into the bores of those cannons. A lookout in

Philadelphia

called out in Arabic, telling them to bear off. Catalano responded, telling the Tripolitan that he was a trader from Malta, he had lost his anchor in the recent storm, and he wished to tie up alongside the big ship just for the night.

There was a moment when not a single breath was taken aboard

Intrepid

as the Americans waited for the reply. A few indistinguishable words drifted across the water, then a number of men climbed down from the frigate's deck into a small boat. They rowed around to

Philadelphia

's bow, took a line that had been lowered, and began rowing toward

Intrepid.

Not wanting the Arabs to get too close, Decatur quickly dispatched his own boat and the two met just a few yards from

Intrepid.

Once the line had been brought on board, the Americans began hauling in.

The gap between the two vessels narrowed as

Intrepid

moved slowly forward. Decatur was relieved when he could look up and no longer see down the bores of

Philadelphia

's cannons. As the ribbon of water separating the ships grew very thin, another line accommodatingly dropped from the frigate's stern. All was going exceedingly well.

As the two ships drew together, someone on the main deck of the frigate noticed that their smaller visitor had an anchor on her forecastle! Suddenly, an alarmed voice cried out: “Americani!”

Frenzied shouts and the rapid rustling of bare feet on wooden decks could be heard in

Philadelphia

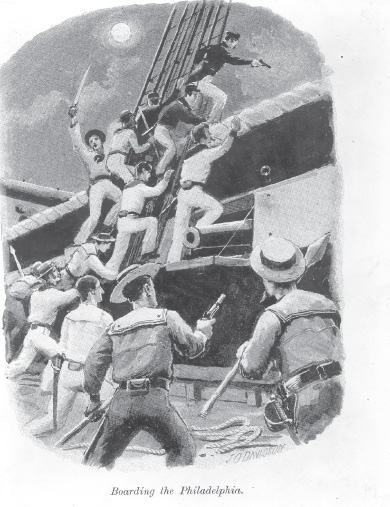

as the Americans frantically pulled on the lines to close the few remaining feet. Then Decatur gave the orderâ“Away boarders!”âand the men began swarming aboard.

Some of the Tripolitans ran below decks, many dove overboard, and others stood their ground and bravely fought. It was a grisly fight. Decatur had ordered that no firearms be used, so the night air was filled with the clash of cutlasses against scimitars and the cries of cleaved men.

Within ten minutes, there was no more opposition. About twenty Tripolitans lay dead, the rest having fled. The Americans moved quickly

through the ship, focused on their main mission of setting fires at key points. They spread tar, lint, and gunpowder about and, on Decatur's signal, they simultaneously tossed lighted candles into their handiwork. There was a virtual explosion as the ship ignited. It happened so quickly that several men were nearly trapped below by the rapidly spreading flames.

The Americans quickly dropped over the side to

Intrepid

's waiting deck and began shoving off. They had some difficulty freeing themselves, and

Intrepid

's sails began to burn as gusts of flame roared out of the frigate's gun ports and steaming tar poured down from the great conflagration above.

Philadelphia

's rigging began burning through, and as lines and stays parted, they flew about like burning whips, some of them coming to rest across

Intrepid

's own rigging. To make matters worse, several shore batteries opened up, one of them scoring a hit through

Intrepid

's topsail.

Managing to free themselves at last, the Americans began pulling at their sweeps to distance themselves from the roaring fire that by now was illuminating the whole harbor and much of the surrounding city. The shore batteries continued to hammer away at the fleeing ship from the large waterfront castle nearby, but they could not find their mark. As if in one last great act of defiance,

Philadelphia

's loaded cannons suddenly cooked off in the great heat, and some of her rounds actually struck the castle walls from which the shore batteries had been firing.

A welcome breeze sprang up and soon

Intrepid

was sailing into the outer harbor, her bow pointed toward the open sea. On their starboard quarter,

Philadelphia

burned in one giant flame like the magnified fire of a single match. Then the fire reached her magazine, and like a volcanic eruption, a massive explosion lifted the great hull into the air and brought it down again, shattered and no longer recognizable as a ship.

Decatur and his men paused at the mouth of the harbor and looked back in awe at what they had done. Then

Intrepid

caught a freshening wind and headed off to rejoin the rest of the U.S. fleet, bringing back a piece of restored honor and every man who had left on the mission. Miraculously, not a single American Sailor or Marine had been killed or even seriously wounded. When word of the feat reached British Admiral Horatio Nelsonâthe most respected naval hero of the timeâhe was reported to have remarked that the burning of

Philadelphia

was “the most bold and daring act of the age.”

Sailors boldly entered the enemy harbor at Tripoli to board the captured

Philadelphia

and set her on fire. When word of the feat reached British Admiral Horatio Nelsonâthe most respected naval hero of the timeâhe was reported to have remarked that the burning of

Philadelphia

was “the most bold and daring act of the age.”

Naval Historical Center

The examples cited here are but a few of the many in the U.S. Navy's history when foolish culprits have dared to tread on this nation's honor, and Sailors have had the dutyâand the commitmentâto seek appropriate retribution. Revenge may not be sweet, as the old proverb goes, but there are times when might must be met with might in order to maintain credibility and to remain a potent deterrent. Al Qaeda dealt the nation a serious blow when they took down the World Trade Center and struck the Pentagon on 11 September 2001, but the subsequent loss of the terrorist training haven in Afghanistan, as well as the ongoing worldwide War on Terrorism, has once again sent the message to those who might consider stepping on the American rattlesnake; they would be wise indeed to heed the warning: Don't Tread on Me.

| Don't Give Up the Ship | 6 |

In September 1813, a group of American Sailors led by American Master Commandant Oliver Hazard Perry built a fleet from scratch and took it into battle against the British on Lake Erie. They were a polyglot groupâin many ways representative of the new and growing nation of various racial and ethnic backgrounds. One in four was black, and alongside the few experienced seamen and untrained militiamen were local Indians and a Russian who spoke not a word of English.

Perry's flagship, USS

Lawrence,

was built from green timber hewn out of the local forests and was named for Captain James Lawrence, who had lost his life during an earlier battle between his ship, USS

Chesapeake,

and the Royal Navy's HMS

Shannon.

Lawrence's inspiring wordsâspoken as he was carried below, mortally woundedâhad been “Don't give up the ship,” so Perry had these words sewn in bright white letters onto a navy blue field to create a unique flag to carry into battle.

Inspired by this flag, the American Sailors were victorious on Lake Erie, causing Perry to send a famous dispatch: “We have met the enemy; and they are ours. Two ships, two brigs, one schooner, and one sloop.”

It was a momentous victory of great strategic significance and, along with a similar victory on Lake Champlain by Sailors led by Thomas Macdonough, helped bring an end to the war.

Today, Perry's flag is on display at the U.S. Naval Academy, and through the ages, those inspiring wordsâDon't give up the shipâhave guided Sailors through times of terrible crisis. Although U.S. Navy ships have been lost in battle and to natural catastrophes in the years since those Great Lakes battles of the War of 1812, many others have been saved by intrepid Sailors who, in the face of great adversity, have met the challenges head-on and simply refused to give up their ships.

In January 2000, USS

The Sullivans

arrived in Aden, Yemen, to take on fuel. This

Arleigh Burke

âclass guided-missile destroyer was not the first ship to stop in the port city near the southern tip of the Arabian Peninsula.

Aden's location at the juncture of the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden, west of the Arabian Sea, makes it a natural fueling stop for vessels transiting these waters.

The ship got her rather unusual name because she commemorates the name of not just one Sailor, as is the more common practice, but

five.

Five brothers, all serving in the same ship during World War II, were lost in a single, terrible night when USS

Juneau

went down in the Battle of Guadalcanal.

An earlier ship named for the Sullivan brothers, a

Fletcher

-class destroyer, served in World War II and the Korean War and played a key role in the Cuban missile crisis of 1962. That ship earned nine battle stars for her service.

The newer

The Sullivans

lay at the Aden facility gulping fuel just two days after the new millennium had begun, her crew unaware that this new century would be marked by a new kind of war, and that at that very moment, evil forces were gathering to do her serious harm.

Not far away, a small boat shoved off from the shore, full of explosives. The boat looked like any number of other local craft, but this one was manned by several fanatics with ties to a group most Americans had never heard ofâal Qaeda, an Islamic extremist organization. These men were determined to die for their cause and to take an American warship with them.

As the boat moved out across the shimmering water, she behaved sluggishly, and soon her gunwales were awash. Fanatical these men were; brilliant they were not! They had miscalculated the effect all those explosives would have on the small craft, and in minutes they found themselves sinking into the warm waters of Aden's harbor. The bad luck that had taken all five Sullivan brothers back in 1942 did not haunt their namesake on this day. USS

The Sullivans

was spared the intended attack; in fact, her crew would not even be aware until much later that they had been targeted.

Ten months later, the al Qaeda fanatics were ready to try again. USS

Cole

steamed into the harbor at Aden on 12 October 2000 to refuel. Like

The Sullivans,

she was an

Arleigh Burke

âclass guided-missile destroyer. Like her predecessor, her crew had no idea they were the intended target of an attack.

This time the fanatics stayed afloat and made their way across the blindingly bright waters, headed for the American warship. It would be another year before 9/11 would waken the “sleeping giant” of America to the reality of the war that had been declared against it, so the men in this boat had the great advantage of surprise on their side. Waving to the crew on the main deck of the large destroyer, the men steered right for her exposed port side. It was 1118 on the day before the Navy's 224th birthday.

Command Master Chief James Parlier and Damage Controlman First Class Ernesto Garcia, the Repair Division Work Center Supervisor, emerged from

Cole

's training room, where they had just concluded a Morale, Welfare, and Recreation Committee meeting, when they suddenly felt the deck move beneath their feet. The lights momentarily flickered off and on, and a television fell from its shelf. It was fortunate that Parlier had been at the meeting in the after portion of the ship; unbeknownst to him, a two-ton reefer had just crashed clear through a bulkhead, destroying his office.