A Singular Woman (6 page)

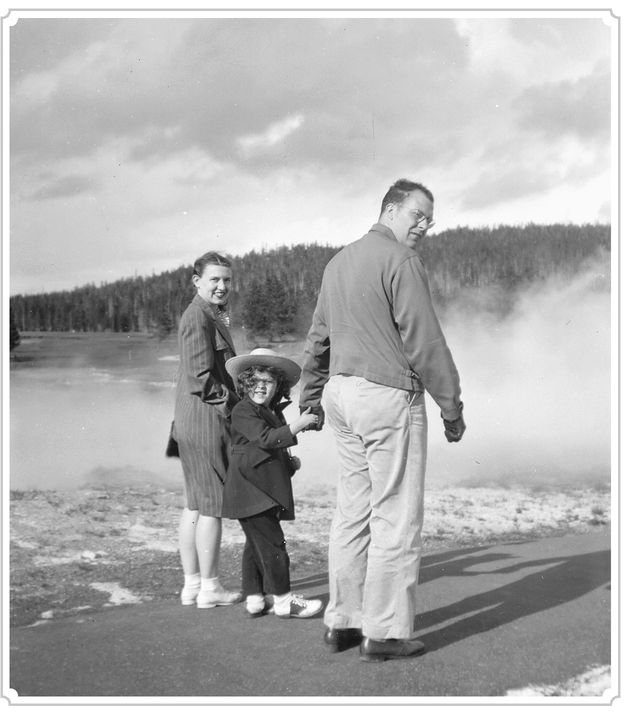

Madelyn and Stanley Dunham

Madelyn's parents were not impressed. Stanley came across to them as a glad-hander, a gadaboutâthe antithesis of the Paynes, Jon said. As Obama described their attitude in his memoir, using the nickname with which he and Maya addressed their grandmother, “The first time Toot brought Gramps over to her house to meet the family, her father took one look at my grandfather's black, slicked-back hair and his perpetual wise-guy grin and offered his unvarnished assessment. âHe looks like a wop.'” Their disapproval did not escape Madelyn's notice. On the evening of the Augusta High School junior-senior banquet in May 1940, Madelyn, at seventeen years old, and Stanley, at twenty-two, slipped out of the banquet and got married in secret. They kept the marriage quiet until Madelyn graduated the following monthâto try to prevent her parents from having it annulled, some of her classmates believed. The news reached Stanley's brother, Ralph, only months later. Charles Payne was away at Boy Scout camp by the time it broke.

“My parents were pretty much crushed that their daughter would go off with someone they didn't really have much respect for,” he told me. “But they accepted it.” Putting as good a face on it as possible, Leona Payne sent out engraved announcements.

Twenty years later, Madelyn Dunham would surely remember her youthful romantic rebellion, her secret marriage, and her parents' reaction, when her daughter, at age seventeen, learned that she was pregnant with the child of a charismatic older man whom she would marry a few months later. Perhaps Madelyn would be struck by the similarities between herself and Stanley Annâheadstrong teenagers swept away by seemingly worldly charmers promising new horizons, the possibility of adventure, and the certainty of escape. Perhaps she thought, too, of Stanley's dead mother, Ruth Armour, who, at an even younger age, had done something similar. To anyone new to the story, Stanley Ann's infatuation, pregnancy, and precipitous marriage to a black student from Kenya might appear to be an inexplicable break with her family's presumably straitlaced, white-bread Kansas history. But Madelyn and Stanley would have known there was a precedent in Madelyn's own decision to override the reservations of her parents and short-circuit any discussion of her future by marrying Stanley and bolting for the coast.

Paradoxically, it may have been on the rim of the Pacific that it first dawned on Madelyn that life with Stanley might prove less dazzling than she had imagined. As soon as school was out, the newlyweds had headed for California, the obvious place for an aspiring writer with a trunk full of unpublished works. But after settling in the San Francisco Bay Area, Madelyn found herself working odd jobs in various quotidian establishments, including a dry cleaner, to help pay the rent, her brother Charles remembered. In later years, she would come to regret deeply that she had never gone to college. She would make sure that her daughter, faced with a similarly abrupt change in life circumstances, was able to stay in school. Madelyn would be the one, too, who would subsidize the education of her grandchildren in one of Hawaii's most respected private schools. But if she thought during that time in California about going back to school, it was not an option. She needed to make money. What was more, after the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, she and Stanley were back in Kansas, just eighteen months after leaving. Six weeks after Pearl Harbor and a few months short of his twenty-fourth birthday, Stanley enlisted on January 18, 1942, as a private in the U.S. Army. According to his enlistment records, he gave his education as “four years of high school” and his civilian occupation as “bandsman, oboe, or parts clerk, automobile.”

The war jolted southeastern Kansas out of the Depression in much the same way that the oil strike at Stapleton Number One, the discovery well at the oil field in El Dorado, had jolted Butler County a quarter-century earlier. Profits from the oil boom had financed a fledgling aviation-manufacturing industry in Wichita, where aviation pioneers such as Clyde Vernon Cessna, Walter Beech, and Lloyd Stearman had helped win Wichita the title “Air Capital of the World.” The Stearman Aircraft Company, then a subsidiary of Boeing, had landed its first major military contract in 1934. Now the attack on Pearl Harbor strengthened the case for decentralizing the defense industry, and Wichita became one of the biggest defense aviation centers in the country. In 1941, the government began construction on a new Boeing plant in Wichita and picked Boeing to produce the B-29 Superfortress, the aircraft later used in the firebombing campaign against Japan. Employment at Boeing soared to 29,795 in December 1943âup from 766 two and a half years earlier, according to Wings over Kansas, a website on Kansas aeronautics. The plant operated around the clock. The population of Sedgwick County nearly doubled over five years. Huge temporary housing complexes with names like Planeview and Beechwood sprang up. Next to the Boeing plant, Planeview alone had a population of twenty thousand. Boeing had fifty-six bowling teams. There was a nine-hole golf course and tennis, badminton, and shuffleboard courts. The company bused in workers from as far away as Winfield, Kansas, and Ponca City, Oklahoma. Others commuted by car pool from places such as El Dorado and Augusta. The defense-aviation boom, like the oil boom, would prove fleeting. In 1945, after the suspension of B-29 production, Boeing laid off sixteen thousand workers in a single day. The new plant closed, and employment at Boeing Wichita dropped to about one thousand. But while the war lasted, wages were high and, with men off at war, nearly half of all the aircraft production workers were women. Nationally, eighteen million women are said to have entered the workforce between 1942 and 1945, many of them because of government campaigns to lure housewives into full-time, war-related work. Women became financially independent and took on male responsibilities, in many cases for the first time. Madelyn Dunham was part of that change.

With Stanley away in the Army, Madelyn moved in with her parents in Augusta and commuted by car pool to a job as an inspector on the night shift at Boeing in Wichita. During his presidential campaign, Mr. Obama described his grandmother in that period as Rosie the Riveterâthe icon of wartime womanhood, in overalls, painted by Norman Rockwell for the cover of

The Saturday Evening Post.

The prodigious work ethic that would enable Madelyn decades later to work her way up from a low-level bank employee to vice president of the Bank of Hawaii must have been in evidence at Boeing. She became a supervisor, Charles Payne remembered, and was soon making more money than their father. Madelyn saved her money, but she also occasionally splurged. Like a character in a Bette Davis movie, she bought herself a fur coat.

The Saturday Evening Post.

The prodigious work ethic that would enable Madelyn decades later to work her way up from a low-level bank employee to vice president of the Bank of Hawaii must have been in evidence at Boeing. She became a supervisor, Charles Payne remembered, and was soon making more money than their father. Madelyn saved her money, but she also occasionally splurged. Like a character in a Bette Davis movie, she bought herself a fur coat.

Davis, who had helped small-town girls like Madelyn while away the Depression, was now one of the country's biggest box-office stars. Her movie

Now, Voyager

became a hit across the country in November 1942, playing to audiences made up mostly of women. The film marked a shift in Davis's image. As the government campaigned to recruit housewives into factory work, Davis shed what Martin Shingler, a film scholar, has described as her previously androgynous look and emerged as “the leading spokesperson for femininity, lipstick and glamour.” The transformation had begun six months earlier, Shingler suggested, with the May 1942 release of

In This Our Life,

in which Davis played Stanley Timberlake, a southern belle.

Now, Voyager

became a hit across the country in November 1942, playing to audiences made up mostly of women. The film marked a shift in Davis's image. As the government campaigned to recruit housewives into factory work, Davis shed what Martin Shingler, a film scholar, has described as her previously androgynous look and emerged as “the leading spokesperson for femininity, lipstick and glamour.” The transformation had begun six months earlier, Shingler suggested, with the May 1942 release of

In This Our Life,

in which Davis played Stanley Timberlake, a southern belle.

That spring, Madelyn Dunham, age nineteen, was pregnant. On November 29, 1942, one month after her twentieth birthday, she gave birth to a brown-eyed, brown-haired daughter with the same delicate coloring so admired in her great-aunt Doris, Miss El Dorado. In

Dreams from My Father,

Obama writes that his mother was born at Fort Leavenworth, the Army base where Stanley was stationed. But Ralph Dunham said he visited Madelyn and the baby in Wichita Hospital when Stanley Ann was a day or two old. Years later, Ann would say that she had nearly entered the world in a speeding taxi. Rushing to the hospital in a snowstorm, she told Maya, Madelyn almost gave birth in the cab. As Ann told the story to Maya, it had a parallel in Maya's birth twenty-eight years later. On that occasion, Madelyn was arriving in Jakarta by plane, and Maya's father, Lolo Soetoro, had gone to the airport to meet her. It was the eve of Independence Day (the Indonesian one), and Ann, waiting in a Catholic hospital in Jakarta to deliver, grew impatient and walked out into the street to look for her husband and her mother. As she told the story, she was on the verge of hopping into a pedicab, called a

becak,

when Madelyn and Lolo finally pulled up. Though delivered in the hospital, Maya, the inheritor of her mother's wanderlust, was nearly born in a

becak.

And Ann, whose adventuring impulse came by way of her Kansan parents, nearly arrived in the Wichita equivalent.

Dreams from My Father,

Obama writes that his mother was born at Fort Leavenworth, the Army base where Stanley was stationed. But Ralph Dunham said he visited Madelyn and the baby in Wichita Hospital when Stanley Ann was a day or two old. Years later, Ann would say that she had nearly entered the world in a speeding taxi. Rushing to the hospital in a snowstorm, she told Maya, Madelyn almost gave birth in the cab. As Ann told the story to Maya, it had a parallel in Maya's birth twenty-eight years later. On that occasion, Madelyn was arriving in Jakarta by plane, and Maya's father, Lolo Soetoro, had gone to the airport to meet her. It was the eve of Independence Day (the Indonesian one), and Ann, waiting in a Catholic hospital in Jakarta to deliver, grew impatient and walked out into the street to look for her husband and her mother. As she told the story, she was on the verge of hopping into a pedicab, called a

becak,

when Madelyn and Lolo finally pulled up. Though delivered in the hospital, Maya, the inheritor of her mother's wanderlust, was nearly born in a

becak.

And Ann, whose adventuring impulse came by way of her Kansan parents, nearly arrived in the Wichita equivalent.

They named her Stanley Ann.

In the years that followed, the explanation most often given was that her father, Stanley, had hoped for a boy. “One of Gramps's less judicious ideasâhe had wanted a son,” Obama wrote. But relatives doubted that that story was true. Ralph Dunham said his brother “probably would have settled for any healthy child.” Maybe he just liked the name. Or maybe that story originated as a joke, delivered teasingly by the great confabulator himself. The fact was, Madelyn was fully in charge of matters such as the naming and handling of the baby, some of her siblings said. Stanley would not have had veto power. “When I asked my grandmother about it, she said, âOh, I don't know why I did that,'” Maya told me. “Because she's the one who named her Stanley. That's all she ever said: âOh, I don't know.'”

On at least one occasion, Madelyn seemed to suggest that she had taken the name from the southern belle in the movie that just six months earlier had signaled the transformation in Bette Davis's image on-screen. When asked about the name not long after Stanley Ann's birth, Madelyn said cryptically, “You know, Bette Davis played a character named Stanley.”

Two

Coming of Age in Seattle

I

t wasn't easy to be a girl named Stanley growing up in the wake of a restless father. By her fourteenth birthday, Stanley Ann had moved more often than many Americans in those days moved in a lifetime. At age two, she had moved from Kansas to California, where Stanley Dunham spent two years as an undergraduate at the University of California at Berkeley; then she had moved from California back to Kansas, where, after dropping out of Berkeley, her father signed up for a couple of courses at the University of Wichita; from Kansas to Ponca City, Oklahoma, where he worked as a furniture salesman; from Ponca City to Texas, to sell furniture again; from Texas back to El Dorado; from El Dorado to Seattle; and from Seattle to Mercer Island, Washington, where the family touched down for four years before heading westward once again, this time to Hawaii, where Stanley and Madelyn finally settled. By the time Stanley Ann entered Mercer Island High School as a thirteen-year-old freshman in the fall of 1956, she was accustomed to being the outsider and the perpetual other. She had some of the attributes of children of peripatetic parents: She was adaptable and self-sufficient. Experienced in the art of introducing herself, she had developed a preemptive response to the inevitable follow-up question. “I'm Stanley,” she would say. “My father wanted a son, but he got me.” The retort, true or not, revealed something about the speaker. By the time she was a teenager, Stanley Ann was witty and self-contained, with a wry sense of humor. She had other outsider qualities: She was curious about people, and she was tolerant, not leaping to judgment. She had an unusual capacity even as a child, Charles Payne told me, to laugh at herself. She also had a contentious relationship with her father. She had figured out early on how to get under his skin.

t wasn't easy to be a girl named Stanley growing up in the wake of a restless father. By her fourteenth birthday, Stanley Ann had moved more often than many Americans in those days moved in a lifetime. At age two, she had moved from Kansas to California, where Stanley Dunham spent two years as an undergraduate at the University of California at Berkeley; then she had moved from California back to Kansas, where, after dropping out of Berkeley, her father signed up for a couple of courses at the University of Wichita; from Kansas to Ponca City, Oklahoma, where he worked as a furniture salesman; from Ponca City to Texas, to sell furniture again; from Texas back to El Dorado; from El Dorado to Seattle; and from Seattle to Mercer Island, Washington, where the family touched down for four years before heading westward once again, this time to Hawaii, where Stanley and Madelyn finally settled. By the time Stanley Ann entered Mercer Island High School as a thirteen-year-old freshman in the fall of 1956, she was accustomed to being the outsider and the perpetual other. She had some of the attributes of children of peripatetic parents: She was adaptable and self-sufficient. Experienced in the art of introducing herself, she had developed a preemptive response to the inevitable follow-up question. “I'm Stanley,” she would say. “My father wanted a son, but he got me.” The retort, true or not, revealed something about the speaker. By the time she was a teenager, Stanley Ann was witty and self-contained, with a wry sense of humor. She had other outsider qualities: She was curious about people, and she was tolerant, not leaping to judgment. She had an unusual capacity even as a child, Charles Payne told me, to laugh at herself. She also had a contentious relationship with her father. She had figured out early on how to get under his skin.

Madelyn, Stanley Ann, and Ralph Dunham, Yellowstone National Park, summer 1947

Other books

Theodosia & the Eyes of Horus by R. L. LaFevers

Double Jeopardy by Colin Forbes

The Accidental Assassin by Nichole Chase

Blue Genes by Val McDermid

Wolf in Man's Clothing by Mignon G. Eberhart

Mafia Captive by Kitty Thomas

La pirámide by Henning Mankell

Murder within Murder by Frances Lockridge

Magnolia Wednesdays by Wendy Wax

Ties That Bind by Elizabeth Blair