A Singular Woman (9 page)

Jim Wichterman, who taught Stanley Ann during her senior year, was a graduate student in philosophy at the University of Washington when he was hired to teach on Mercer Island. The principal of the high school assigned him to teach “contemporary world problems” to seniors, who were barely ten years younger than he was. Since contemporary world problems were philosophical problems, he figured, why not teach philosophy? He did that for seventeen years, thundering through Plato, Aristotle, Saint Augustine, Descartes, Hobbes, Locke, Mill, Marx, Kierkegaard, Sartre, and Camus. After Mercer Island, he taught philosophy at a private school in Seattle for another twenty-two years. He never got his Ph.D., but that had ceased to matter. When I met him in the summer of 2008, he was pushing eighty and still teaching philosophyâthis time at the Women's University Club in Seattle and in a night class for adults on Mercer Island. “I had a circus teaching,” he said. “I should have paid them.” The feeling appears to have been mutual. In high school annuals in the late 1950s, Mercer Island students wrote about Wichterman more often than almost any other teacher. In conversations a half-century later, Stanley Ann's classmates described Wichterman's class as an intellectual coming of age.

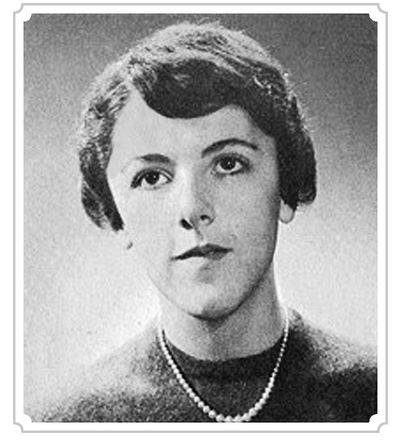

At seventeen, from the 1960

Mercer Island High School annual

Mercer Island High School annual

His method, modeled on his graduate-school courses, was total immersion. His students read constantly and in enormous quantities. There were research papers every six weeks. In tutorials, students critiqued one another's work. Knowledge is about questions, Wichterman told them. Is the world absurd? Does God exist? What constitutes good? “What do you think that means, Miss Botkin? Miss Dunham?” Susan Botkin Blake recalled Mr. Wichterman asking. How do these ideas relate to the present? Maxine Box remembered typing until three in the morning. “We were the higher-percentile bunch,” said Steve McCord. “We thought of ourselves as being brighter than most people at most schools. We were aware of our uniqueness, whether it was real or imagined.”

Down the hall, Val Foubert, their humanities teacher, assigned

The Organization Man, The Hidden Persuaders, Atlas Shrugged,

and

Coming of Age in Samoa.

Kathy Powell Sullivan recalled, “We devoured Jack Kerouac.

On the Road

would have been our bible.” Conformity was disdained; the very idea of difference was alluring. Foubert, a World War II veteran who some said moonlighted as a drummer in a swing band, is said to have eventually defected to another district in a disagreement over Mercer Island's handling of parents' complaints about his reading list. Parents complained, too, that Wichterman had no business teaching a college course in high school. The course was making trouble at home. “You know how kids are,” Wichterman told me. “They see an idea they get in class, they set that up at the dinner table with Dear Old Dad. Dad gets up out of his chair, all exercised. Of course, the kids love that. You don't start out to cause trouble at the dinner table; what you start out to do is get the kid on his tippy toes: âIf you don't like this argument, refute it. Give me reasons you don't like it. You have to

think

.'”

The Organization Man, The Hidden Persuaders, Atlas Shrugged,

and

Coming of Age in Samoa.

Kathy Powell Sullivan recalled, “We devoured Jack Kerouac.

On the Road

would have been our bible.” Conformity was disdained; the very idea of difference was alluring. Foubert, a World War II veteran who some said moonlighted as a drummer in a swing band, is said to have eventually defected to another district in a disagreement over Mercer Island's handling of parents' complaints about his reading list. Parents complained, too, that Wichterman had no business teaching a college course in high school. The course was making trouble at home. “You know how kids are,” Wichterman told me. “They see an idea they get in class, they set that up at the dinner table with Dear Old Dad. Dad gets up out of his chair, all exercised. Of course, the kids love that. You don't start out to cause trouble at the dinner table; what you start out to do is get the kid on his tippy toes: âIf you don't like this argument, refute it. Give me reasons you don't like it. You have to

think

.'”

It may have been in Art Sullard's tenth-grade biology class that Stanley Ann fell in with the group of boys who would become her closest friends in her last two years on Mercer Island. Sullard, also young and a musician, would banter with certain students and occasionally make sarcastic asides. Over dissections, students milled around in groups, the humor tending toward black. Stanley Ann's somewhat sarcastic sensibility surfaced. “My seatmate was an old athlete friend, very intelligent,” John Hunt recalled. “I remember him making comments about Stanley because he was trying to figure out what was with her. She was so different.” The following year, she was assigned to a chemistry table next to one occupied by Hunt, Bill Byers, and Raleigh Roark. They all became friends, fancying themselves as thinkers on the cultural cutting edge. Byers was slightly older than the others, had access to a car, and had glimpsed the wider worldâSeattle and Bellevue, anyway. He had friends off the island and, at sixteen, had started dating a girl in Seattle. The son of a liquor-company manager who had abandoned graduate work on Chaucer in order to find paying work during the Depression, Byers was reading Dostoyevsky, listening to Pete Seeger, and borrowing old classical records from the high school librarian. Outside of school, he and a friend would amuse themselves by making gunpowder out of saltpeter, charcoal, and sulfur and creating small explosions in the woodsânot to damage anything, just for fun. In the classroom, he was a contrarian on principle. Byers remembered Raleigh Roark as having “a very original type of intelligence. You could count on him saying or doing something that just went crosswise with the accepted norms.” Roark had a half sister living in bohemian splendor in the university district of Seattle, from whom Roark's friends got a first glimpse of a counterculture. They discovered foreign films at theaters in Seattle. “Satyajit Ray's Apu Trilogy was one that hit us the hardest,” Hunt remembered. “It was totally different from anything we'd seenâThird World poverty, a complete cultural gulf. We had no experience, we hadn't even read about that. We would go and sit and talk and talk. What did it mean? What's it got to do with us? We were trying to acquaint ourselves at second- and thirdhand, and wondering what to do about it.” There were coffeehouses in the university district where it was possible to spend hours drinking espresso, eating baba au rhum, sitting on pillows, and listening to classical guitar and jazz. “We'd get in Bill's car, do anything, go for a picnicâanything to get away from the families and to talk,” Hunt said. “We all had a very strong need to talk about things we didn't talk about at home.” Kerouac's

On the Road

conjured dreams of escape, Roark remembered. San Francisco was Mecca.

On the Road

conjured dreams of escape, Roark remembered. San Francisco was Mecca.

Stanley Ann, often the only girl in the group, shared the boys' highbrow pretensions and what Byers described as their us-against-them outlook toward “the dominant culture, the not-very-thoughtful people doing not-very-thoughtful things.” He said, “I think it was a big issue for herâthese kinds of people that she disliked. My feeling is she did feel ostracizedâthat she felt that she could never have been one of them even if she had wanted to be one of them, that type of feeling.” Unconventional in many ways, she also had a conservative streak. Once, Byers drove her out to Bellevue to meet some friends he had made who were in the process of becoming, in effect, early hippies. Their style of living fascinated Byers. Stanley Ann looked the scene over. “You know, I couldn't live in that place,” she told him later. “It's filthy.” Which was true, Byers remembered later. “Somewhere, fundamentally, she had a fairly rock-solid, realistic, even conservative outlook,” he said. “She knew where the line was, it seemed. She was right about those people. By their lights, they were living free of all these restraints. But of course, that meant free of . . .”

He paused.

“. . . hygiene.”

By senior year, Stanley Ann's friendship with Kathy Powell had cooled. Kathy had met Jim Sullivan, a fraternity man from the University of Washington, at the Pancake Corral. Because he was five years older than she was, she had lied to him about her age. Now she was wearing his fraternity pin. In Stanley Ann's eyes, Kathy Sullivan told me, she had sold out. Stanley Ann defined herself by her intellect, Sullivan said. If she had any romantic interest in boys, she did not let on. In the spring of 1959, Jim Sullivan suggested to Kathy that he fix up some of his fraternity brothers with her friends. When Kathy suggested including Stanley Ann, Jim dropped her from the list in favor of a girl thought to be the most beautiful in the school. “She wasn't a radiant beauty by any means,” Byers said of Stanley Ann. “But, probably more to the point, she was very intellectual, and she could cut people down. She didn't suffer fools gladly.” She would have needed some coaching, Kathy felt, not to be supercilious and disdainful to Jim's fraternity friends.

In early 2009, I heard the name Allen Yonge. If Stanley Ann had ever had a boyfriend in high school, I was told, it could have been Allen. He was a year or two older than she was and lived in Bellevue, though no one seemed to remember how they had met. For a time, friends of theirs said, he developed a crush on Stanley Ann. She seemed willing, sort of, to give it a try. I found an address for Mr. Yonge and sent him a letter asking if he would speak with me. In early March, I received an e-mail from his wife, Penelope Yonge. Her husband was astounded to get my letter, she said: “Allen is enthusiastic about Obama, but he had never connected his Mercer Island friend Stanley with the president, so this came as quite a surprise.” However, he was recovering from an accident and not in a condition to talk. He would get back to me, she said, when he was in better shape. Several months later, I wrote to her to say I was still interested whenever her husband felt up to speaking. She e-mailed back two days later to tell me that he had died. “He had been looking forward to talking to you about Stanley,” she said. “He remembered her with great affection and admirationâhe called her âbrainy' and âintellectual' and âadventurous' and âa whole lot of fun' (descriptions that aren't usually used together, at least not in high school).”

Stanley Ann was, indeed, adventurous. In the summer of 1959, Steve McCord proposed an unusual late-night outing. At a time when homosexuality was kept well hidden, he had developed a crush on a younger boy and had confided in Stanley Ann. He suggested they sneak out late one night, walk to the boy's house at the far end of the island, and watch him through his window while he slept. Stanley Ann was game, McCord recalled when he told me the story; she was a person who was just “up for adventure.” (And if she ever felt inner turmoil about a decision, Byers told me, she did not let on: “When she decided to do something, she decided to do it.”) So on a warm, breezy night and at the appointed hour, she climbed out her bedroom window onto the moonlit lawn of the Shorewood complex. McCord was waiting, and they set off, heading south. They walked several miles to the house, found the window, executed their mission undetected, then walked several miles homeâonly to be confronted by Big Stan, stationed in the bedroom window, arms akimbo, awaiting their return. His reaction was stern but not explosive, as McCord recalled it: “It was, âYoung lady, you get in here. And

you

, go home!'” The episode blew over, it seems, without dire consequences for Stanley Ann. But it proved to be a precursor to a far more daring adventure a few months laterâa spontaneous breakout that shattered the written and unwritten codes of conduct that kept Mercer Island teenagers on the straight and narrow. It was an act of rebellion that Stanley Ann's father would be unlikely to forget.

you

, go home!'” The episode blew over, it seems, without dire consequences for Stanley Ann. But it proved to be a precursor to a far more daring adventure a few months laterâa spontaneous breakout that shattered the written and unwritten codes of conduct that kept Mercer Island teenagers on the straight and narrow. It was an act of rebellion that Stanley Ann's father would be unlikely to forget.

Fifty years later, no one seemed to agree on exactly when the escapade went down. Bill Byers thought it took place during the fall, but John Hunt initially remembered the time of year as spring. Either way, it was nighttime and they were driving home to Mercer Island, maybe from a coffeehouse in Seattle, with Stanley Ann. They were in Hunt's parents' car, and Hunt was at the wheel. The conversation turned negativeâone of those “This really sucks, school is irrelevant, why bother to go home?” conversations of adolescence, as Hunt described it. Suddenly, someone suggested not going home: They could keep on driving. They could drive to San Francisco. Hunt balked, stunned by the suggestion. He might have expected it of Bill, he said later, but he had no idea that Stanley Ann “had got to the point of just wanting to go chuck it.” They began to argue. The argument turned acrimonious and tearful. Hunt tried to talk the others out of it, he told me, visibly anguished by the memory a half-century later. They begged him to join them. But the lark struck him as pointless: They would get in trouble for cutting school; they would be runaways; if the other two went without him, he would have to lie to cover their tracks. “He was certainly torn,” Byers remembered. “But he was a sensible person, basically. He would never do a thing like thatâwhich was totally irresponsible and totally crazy and downright dangerous and not even practical.” As for Stanley Ann, he said, “She was all for it. Otherwise, it would never have happened. I guarantee it. She would have said, âNo. Take me home.' She didn't.” So it was settled. Hunt dropped off the other two at the Byerses' garage, where Byers parked the metallic-green 1949 Cadillac convertible that his father no longer used. The garage was beside the road, uphill from and out of earshot of the house. “Please don't do this,” Hunt pleaded. “You're going to ruin things for everybody.”

Byers and Stanley Ann headed south in the Cadillac. They had only the money in their pockets and the clothes they were wearing. When Byers and I spoke, his memory of details of the trip was spotty. He said he had forgotten most of what happened, including the route they drove, how long they were away, what they talked about in the car. But, he made clear, it was a road trip. It was neither romantic nor an elopement. He remembered a few episodes in some detail. They picked up a mild-mannered drifter who did them the favor of extracting the car radio from the dashboard to sell it to a gas station attendant when cash ran short. Byers remembered pulling off the road to sleepâthe two men in the front seat, Stanley Ann in backâand being awakened in the night by the sound of whimpering. The hitchhiker had swiveled around in his seat and was groping in Stanley Ann's direction, “softly asking her to âbe nice' to him, while she shrank as far away from him as she could,” Byers told me. Byers barked at the man, who swung forward and mumbled an apology. “I do not remember feeling frightened. I think I was just angry,” Byers told me. “I am most certainly not a brave person. I guess I was naive enough to not consider the possibility of having a rapist or homicidal maniac on our hands.” As for Stanley Ann, faced with the unwanted advances of a stranger, she was visibly afraid. It was the only time, Byers told me, that he could remember seeing her in a situation out of her control and feeling frightened.

Other books

Football Fugitive by Matt Christopher

Evolution by Greg Chase

Stolen Magic (Dragon's Gift: The Huntress Book 3) by Linsey Hall

Twilight by Kristen Heitzmann

Fear to Tread by Michael Gilbert

THE RISK OF LOVE AND MAGIC by Patricia Rice

Grand Canary by A. J. Cronin

Summer in Good Hope (A Good Hope Novel Book 2) by Cindy Kirk

Fast and Loose by Fern Michaels

Time and Again by Jack Finney, Paul Hecht