A Teardrop on the Cheek of Time: The Story of the Taj Mahal (10 page)

Read A Teardrop on the Cheek of Time: The Story of the Taj Mahal Online

Authors: Michael Preston Diana Preston

Tags: #History, #India, #Architecture

A mid-seventeenth-century Moghul painting of a turkey

.

Jahangir also particularly admired European miniature portraits presented to him by foreign visitors and launched a new fashion at court of bejewelled miniatures to be hung around the neck or attached to the turban. A favoured few were permitted the privilege of wearing tiny likenesses of the emperor himself.

Another of Jahangir’s interests was architecture. He took great satisfaction in completing a ‘magnificent sepulchre’ for his father at Sikandra, near Agra. Akbar had commissioned the mausoleum during his own lifetime but, on a tour of inspection, Jahangir did not find the design sufficiently striking: ‘My intention was that it should be so exquisite that the travellers of the world could not say they had seen one like it in any part of the inhabited earth.’ Instead, while he had been preoccupied with Khusrau’s revolts, ‘the builders had built it according to their own taste, and had altered the original design at their discretion’. Jahangir ordered ‘the objectionable parts’ to be pulled down and employed ‘clever architects’ so that ‘by degrees a very large and magnificent building was raised, with a nice garden round it, entered by a lofty gate, consisting of minarets made of white stone’. The four minarets of shining white marble were an innovation but would become one of the most distinctive features of high Moghul architecture. An inlaid tracery of lilies, roses, narcissi and other flowers, delicate as lace, covering Akbar’s marble cenotaph also prefigured what was to come.

Jahangir succeeded in his objective of astonishing the traveller. Even while the tomb was still under construction, William Finch marvelled at the huge monument built to contain a monarch

‘who sometimes thought the world too little for him’

. In the early 1630s another Englishman, Peter Mundy, who sketched the building, wrote that it ranked among the seven wonders of the world. However, thirty years later a French visitor to India would write that, lovely though Akbar’s tomb was, he would not describe it, since

‘all its beauties are found in still greater perfection in that of the Taj Mahal’

.

*

With Khusrau neutralized and his empire settling into stability and tranquillity, Jahangir’s affections focused increasingly on Khurram, whom he had only come to know well after Akbar’s death. The young prince excelled in the martial arts and shared his interests, even exceeding his father’s love of fine buildings. In 1607, the emperor visited a house Khurram had had built and judged it ‘truly a harmonious structure’. In 1608, and overlooking the claims of his other son, Parvez, just over two years older than Khurram, Jahangir awarded the sixteen-year-old youth the territory of Hissar Firoza in the Punjab and the right to pitch a crimson tent – honours traditionally awarded to the emperor’s chosen heir.

The Royal Meena Bazaar was a courtly replica of a real bazaar. This

‘whimsical kind of fair’

, as a French visitor described it, took place by night in scented gardens lit with flickering candlelight and coloured lanterns swaying from the branches of trees and in the background the splashing of fountains. The wives and daughters of the nobility spread stalls with gold and silver trinkets and swathes of silk and played the part of traders, bantering and bargaining with their would-be purchasers – royal matrons and princesses and, of course, the emperor and his favoured male relations. This festive, intimate occasion was one of the few times that the women were allowed to drop their silken veils and let the soft light fall on their carefully made-up faces. It was a fine opportunity for any woman to show off a handsome daughter. Khurram could gaze openly on Arjumand Banu, who would hold him emotionally and sexually for the rest of her life.

Court historians recorded the betrothal in their usual flowery language, praising the young woman as

‘that bright Venus of the sphere of chastity’ and extolling her ‘angelic character’ and ‘pure lineage’

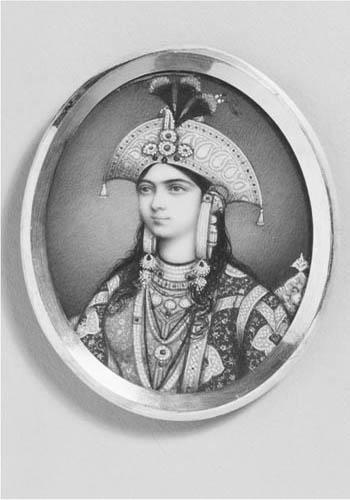

. All accounts, official or not, agree that Arjumand Banu was exceptionally beautiful at a court where beauty was not in short supply. However, images of the future Mumtaz Mahal, the Lady of the Taj, are tantalizingly elusive. A contemporary Moghul portrait claimed by some to depict her shows, in profile, a fine-featured young woman with delicately arched brows, a soft, tranquil expression and a pink rose in her hand. A golden veil half conceals her long black hair, and strings of pearls intertwined with rubies and emeralds are twisted around her smooth throat and narrow wrist, and her fingertips and palms are hennaed. The only other portrait, reputedly copied from an earlier original in the late nineteenth century, depicts a girl in a bejewelled diadem, with elongated dark eyes, graceful curving brows and, once again, a rose in her hand.

Yet within just a few months of the betrothal, Arjumand Banu’s family suffered a dangerous reverse. On his accession, Jahangir had appointed Ghiyas Beg to be his revenue minister, awarding him the title Itimad-ud-daula, ‘Pillar of Government’. The Persian courtier’s administrative talents were well suited to the task, but a contemporary wrote of his lavish corruption,

‘in the taking of bribes he certainly was most uncompromising and fearless’

. First he was charged with embezzlement, but far more serious accusations followed. One of Ghiyas Beg’s sons was among the only four conspirators executed by Jahangir for their involvement in Khusrau’s final plot to assassinate the emperor. Ghiyas Beg himself was implicated and arrested and only narrowly escaped execution. He saved his life and secured his rehabilitation by paying Jahangir an enormous sum, presumably out of the proceeds of his corruption. He cautiously resumed his rise as ‘Itimad-ud-daula’, Jahangir’s ‘Pillar of Government’, but the risk to the family had been considerable.

A nineteenth-century portrait said to be of Mumtaz Mahal and to have been copied from a seventeenth-century original

.

Itimad-ud-daula’s slip from grace and the execution of his son perhaps explain why the marriage between his granddaughter and Khurram did not take place for five years – an exceptionally protracted engagement when the partners were of marriageable age. In the meantime Khurram contracted, at Jahangir’s behest, a dynastic alliance. In October 1610 he wed another Persian girl – a princess descended from Shah Ismail Safavi of Persia – who bore him his first child, a daughter, in August 1611. The cloud over her family, her protracted engagement and the thought of Khurram with another woman could not have been easy for Arjumand Banu, waiting anxiously and impotently in her father’s harem.

Everything changed for Arjumand Banu in 1611 with the marriage of her aunt, Itimad-ud-daula’s daughter, to Jahangir. Four years earlier, the then thirty-year-old Mehrunissa had returned to the imperial court a widow. Her warrior husband Sher Afghan had been slain in Bengal in revenge for killing Jahangir’s foster-brother – an act which deeply angered Jahangir and may have contributed further to the disgrace of Ghiyas Beg’s family. European accounts of the period paint a more lurid and fevered picture, claiming that Jahangir had expressly sent his foster-brother to Bengal to murder Sher Afghan so that he could possess Mehrunissa and that Sher Afghan, suspecting something, had struck first. Certainly, after her husband’s death, the emperor summoned Mehrunissa to Agra, where she joined the household of one of Akbar’s senior widows in the imperial harem. However, once there, she apparently remained

‘for a long time without any employment’

and there is no evidence that she and Jahangir met.

Most likely Mehrunissa first attracted Jahangir during the Nauroz celebrations of 1611. According to one chronicle,

‘her appearance caught the King’s far-seeing eye, and so captivated him that he included her amongst the inmates of his select harem’

. According to another,

‘the stars of her good fortune commenced to shine, and to wake as from a deep sleep … desire began to arise’

. Within two months the two were married at a glittering ceremony. Jahangir’s love of finery and luxury far exceeded his father’s and he delighted in jewels, wearing a different set every day of the year. Given that he had inherited 125 kilos of diamonds, pearls, rubies and emeralds alone – amounting to 625,000 carats of gems – he could indulge his tastes. To the English ambassador he appeared not so much clothed as laden with gems

‘and other precious vanities, so great, so glorious … His head, neck, breast, arms, above the elbows, at the wrists, his fingers every one, with at least two or three rings, fettered with chains … Rubies as great as walnuts, some greater; and pearls such as mine eyes were amazed at.’

The Great Moghul on his wedding day must have been a brilliant spectacle.

Jahangir gave his new bride the title ‘Nur Mahal’, ‘Light of the Palace’, and she was to be his last official wife. In 1616 he would bestow on her a yet more exalted name – ‘Nur Jahan’, ‘Light of the World’. In his memoirs he wrote that ‘I do not think anyone was fonder of me’. Jahangir promoted her family again and rewarded them. Itimad-ud-daula, previous indiscretions forgiven, received increased rank and a huge amount of money. Jahangir honoured his son, Arjumand Banu’s father, with the gift of one of his special, razor-sharp swords, Sarandaz, ‘Thrower of Heads’. (In 1614 Jahangir would award him the title ‘Asaf Khan’, the name by which he would be known for the rest of his long and influential career.) However, amid all her new glory Nur had at least one critic. Jodh Bai, Khurram’s quick-witted, sharp-tongued mother, was scornful of the new arrival in the imperial harem. According to one story, when Jahangir told Jodh Bai that Nur had praised his sweet breath, the acerbic Rajput princess snapped that only a woman with experience of many men could judge whether one man’s breath was sweet or sour.

As if to compensate for the long delay, the nuptials were celebrated with all the pomp and ostentation that a hugely wealthy empire could provide. Jahangir took personal charge, making arrangements for ‘the means of festivity and the requisites of joy and pleasure on such a scale as befits the emperors of very great grandeur’. He continued: ‘I went to Khurram’s house and spent a day and a night there. He presented offerings for my inspection, arranged favours for the begums, his mother and stepmothers and the harem servants and gave robes of honour to the amirs.’ Khurram’s gifts included ‘peerless jewels and heart-pleasing stuffs’. Khurram’s friends carried gifts of money and precious gems to the bride’s house and he followed them in sumptuous state, mounted on a huge elephant.

*