A Teardrop on the Cheek of Time: The Story of the Taj Mahal (30 page)

Read A Teardrop on the Cheek of Time: The Story of the Taj Mahal Online

Authors: Michael Preston Diana Preston

Tags: #History, #India, #Architecture

Once the main framework of the buildings had been constructed the next task was their decoration and ornamentation. Although the mausoleum at a distance looks completely white, the marble is in fact extensively decorated with calligraphy, stone carving and inlay both inside and out. Calligraphy – decorative writing – is considered an art form in the Islamic world, as it is in China and Japan. Both the Arabic and Persian scripts used in the Taj Mahal’s calligraphy are, with their swirling fluid lines and frequent dots, inherently decorative. Fine calligraphy was more prized than painting. One of Shah Jahan’s court poets described how

‘each line’ of some beautiful calligraphy was ‘as heart ravishing as the province of Kashmir’

. According to Islamic traditions, the words of the Koran – the first known book in Arabic – are divine both in form and in content. Given the prohibitions placed in the eighth century on animal and human images – whether painted or sculpted and however religious their motives – for fear of idolatry or the assumption by man of God’s creative function, Koranic inscriptions are a key ornament to many buildings and in particular to mosques.

*

In the Taj Mahal the calligraphy was designed not only to instruct visitors and to condition their response but also to serve a decorative function.

Persian calligraphers were celebrated for producing imaginative versions of their own and Arabic script and Shah Jahan appointed a Persian, Amanat Khan, as the calligrapher for the Taj Mahal. He was a scholar from Shiraz, a well-known centre of Islamic learning, and had come to the Moghul court early in the seventeenth century with his brother, Afzal Khan, who became one of Shah Jahan’s most important officials. Amanat was sufficiently well known as a calligrapher by around 1610 to have been appointed by Jahangir to undertake the calligraphy on Akbar’s tomb, which, according to his signed inscription, dates from 1022 in the Islamic calendar (1612/13 in the Western calendar). Amanat also undertook such official duties as providing official escorts for ambassadors. His inspection seal is found on several manuscripts from the imperial library, where he could well also have had some responsibilities.

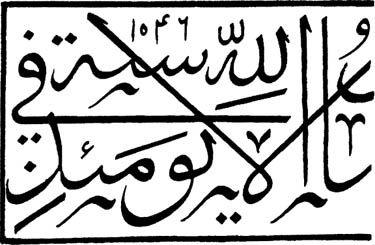

Amanat Khan’s signature on the bottom of the mausoleum’s south arch

.

Amanat Khan, who was the only person allowed by Shah Jahan to inscribe his name on his work on the Taj, signed and dated his calligraphy in two places. One inscription above the south arch on the interior of the mausoleum is dated 1045 (1635/6), and another, towards the bottom of the same interior arch, is dated 1048 (1638/9). There is also an unsigned inscription simply recording the date of the work on the bottom left of the arch on the western exterior of the tomb, 1046 (1636/7). These three inscriptions are important beyond proving that Amanat Khan was the calligrapher. They show that the structure of the mausoleum was sufficiently complete for work to begin on interior decoration no more than, at most, four years after construction had started and that exterior decoration was at an advanced stage only a year later. Second, the positioning of the two interior dates shows that Amanat Khan and his team started at the top of the building and worked down.

Amanat Khan would first have agreed the size, framing and location of the calligraphy with the architectural and construction team. Apart from some of the inscriptions on the imperial cenotaphs and the date and calligrapher inscriptions which are in Persian, all the rest of the calligraphy consists of writings from the Koran in the original Arabic. There are over twenty-five such passages, a greater number than on any other building, including mosques constructed under Shah Jahan. Usually a religious leader would have chosen the text from the Koran, but Amanat, as a scholar and respected member of the Moghul court as well as an experienced calligrapher, is likely to have chosen his texts himself, perhaps even in discussion with Shah Jahan.

Once the content and location were decided, Amanat Khan would have designed the calligraphy in his studio, writing it full-size on large sheets of paper. In doing so, he would have tried to meld form and content into a singular intellectual beauty. The resultant design would then have been traced onto the marble and stone-cutters would have chiselled channels into the stone, into which they inserted black stone to form the writing. Particularly interesting, especially to those who cannot read the script itself, is the calligraphy around the entrance arch to the mausoleum and the southern gateway to the mausoleum complex. In both locations Amanat Khan varied by minute amounts the size and thickness of the lettering and the spacing between it to negate the distorting effect of height and thus to ensure that the fluid lettering appears of a uniform proportion from human eye level, rather than diminishing with height.

As the main entrance to the Taj complex, the southern gateway was designed by the architects to prepare the visitor for what lay beyond. It is, in fact, a large building. Its octagonal floor plan derives, like that of the mausoleum itself, from the chamfering of the square. At the corners are octagonal towers topped with a single white domed octagonal

chattri

. The building is faced with red sandstone but, as one of the complex’s main features, sumptuously inlaid with white marble, particularly around the entrances on its northern and southern sides, which are set into large

iwans

. On the top of the frame of both

iwans

sits a line of eleven small white marble domed octagonal

chattris

. The entrance door blocks the view of the Taj Mahal until the visitor is admitted. Instead, their eyes are drawn to the calligraphy set into the frame of the southern

iwan

. There are many powerful lines but the following in particular make clear that the visitor is invited to enter a spiritual place – an earthly equivalent of the heavenly paradise:

But O thou soul at peace

,

Return thou unto thy Lord, well-pleased, and well-pleasing unto Him

,

Enter thou among my servants

,

And enter thou My Paradise

.

Amanat Khan’s work moved onlookers. One of Shah Jahan’s court historians described how

‘The inscriptions on both the interior and exterior – comprising chapters from the Koran and verses referring to Divine Mercy – have been inlaid in utmost lavishness and artistry, with the subtlety of genius … and the point of the stone-cutting chisel displaying such delicate freshness and colour as to surpass the artistic skill of the sky and draw the line of invalidation and sign of cancellation across the calligraphical writing [of others].’

In 1632, just after the work on the Taj Mahal had begun, Shah Jahan had increased Amanat’s rank, which brought a higher income, and a year later promoted him again, this time to the rank of a commander of 1,000. Both promotions seem to have honoured his position as calligrapher of the Taj Mahal. In December 1637, when work on the calligraphy of the main mausoleum was seemingly nearing completion, Shah Jahan gave Amanat an elephant as a reward for the beauty of his inscriptions inside the tomb. Amanat Khan died some time in the eighteenth year of Shah Jahan’s reign (1644/5). How long he worked on the tomb is unknown, but, since there is an unsigned inscription on the gateway to the Taj Mahal complex dated 1057 (1647), another calligrapher must have been employed at some time.

‘All over the interior and exterior of the mausoleum, especially on the platform containing the illuminated cenotaph, carvers of rare workmanship, with delicate craftsmanship, have inlaid a variety of coloured stones and precious gems – the jewels of whose description cannot be contained in the ocean of speech, nor may even the most ordinary degree of whose narration be achieved through the faculty of speech and discourse. And compared to its beautiful execution, which possesses infinite degrees of beauty, the masterpieces of Azrang and the picture galleries of China and Europe have no substance or reality, and appear like mere reflections on water.’

So wrote Shah Jahan’s historian Salih about the remarkable decoration throughout the Taj Mahal.

Unsigned but dated inscription on the Taj Mahal gateway

.

When he visited the Taj in 1663, François Bernier described how

‘Everywhere are seen the jasper and jade as well as other stones similar to those that enrich the wall of the grand duke’s chapel at Florence, and several more of great value and rarity, set in an endless variety of modes, mixed and enchased in the slabs of marble which face the body of the wall. Even the squares of white and black marble which compose the pavement are inlaid with these precious stones in the most beautiful and delicate manner imaginable.’

Today the decoration of the Taj Mahal still strikes the visitor not only with its good taste and restraint, which prevent it from overwhelming the architectural form, but also with the skill and sensuous delicacy of its execution. In addition to the inset calligraphy, the Taj Mahal’s builders used three main types of ornamentation: intricate stone inlays, relief carvings and, in the mosque and guesthouse, incised, painted decoration. In each case, floral themes dominate. Moghul artists worked away with chisel or inlay to depict flowers such as the iris, lily, lotus and tulip.

In both Asia and Europe there was in the seventeenth century a much more generally understood use of trees and plants as symbols than in the West today, where red roses for love are perhaps the only flowers with such widely appreciated symbolic significance. Flowers were often used in Islamic and, in particular, Persian art and design as symbols of paradise. Persian poets described them as springing from the waters of paradise. Their use in the decoration of the Taj Mahal reinforced the message that the complex was intended to evoke an earthly paradise.

However, going beyond symbolism, from Babur onwards the Moghuls all had a special love for the natural beauty of flowers in their earthly manifestations in gardens. Motivated partly by his interest in natural science as well as in gardens, Jahangir had studied ‘the sweet-scented flowers’ of India, which he thought exceeded all others in beauty. His passion for painting had led him to receive many Western paintings of plants and blooms, including illustrations from the detailed herbals then appearing in Europe. These drawings led to the introduction of a more naturalistic representation of flowers in all Moghul decorative arts. For the first time, for example, plants were shown in vases or growing in earth or in pots, as in the tomb of Itimad-ud-daula. Another sign of renewed European influence was the sudden reappearance of acanthus foliage, which had disappeared after India’s early contact with the Graeco-Roman world.

Shah Jahan added a further ingredient to the mix – his love and knowledge of jewels. According to the French jeweller Jean-Baptiste Tavernier,

‘In the whole empire of the Great Moghul, there was no one more proficient in the knowledge of stones than Shah Jahan.’

His passion for jewels can be seen in the nature and value of the gems inlaid in the Taj Mahal and in the attention to decorative detail and finish. Indeed, the extraordinary craftsmanship led the nineteenth-century Bishop Heber of Calcutta to make a widely quoted remark that the Taj Mahal was built by giants and finished by jewellers. Others have seen the Taj Mahal itself as a white marble jewel set in a sandstone casket formed by the rest of the complex.