A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (136 page)

Read A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War Online

Authors: Amanda Foreman

Tags: #Europe, #International Relations, #Modern, #General, #United States, #Great Britain, #Public Opinion, #Political Science, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #19th Century, #History

A few minutes later, just after the curtain had risen for the third act of

Our American Cousin,

Booth talked his way into the presidential box and fired a single shot into the back of Lincoln’s head. Before anyone could stop him, Booth leaped over the balustrade and onto the stage, the petrified actors watching helplessly as he hobbled out the back. Lincoln was carried to a house across the street where he lingered, unconscious, for nine hours, his decline observed by the cabinet and several doctors. Mary Lincoln became so hysterical that she was removed from the room several times, and she was absent when Lincoln took his final breath at twenty-two minutes past seven in the morning.

Seward lived, though his throat had been slashed several times and his right cheek nearly sliced off as he tried to fight his attacker. Frederick was in a coma, his skull broken in two places, and Augustus had suffered two stab wounds to the head and one to his hand. The secretary of state drifted in and out of consciousness for several days, unaware that Lincoln was dead or that Andrew Johnson had been sworn in as the seventeenth president of the United States. Although propped up on pillows so he could watch Lincoln’s funeral procession on April 19, Seward admitted later that the black funeral plumes passing beneath his window had caught his eye but failed to register with him as anything significant or untoward.

26

On April 21, Lincoln’s funeral train pulled away from Washington station at 7:00

A.M.

and began its seventeen-hundred-mile journey to Springfield, Illinois.

38.3

That day, in Virginia, the raider John Singleton Mosby disbanded his Partisan Rangers, although Mosby himself refused to give his parole. His two British volunteers confounded the Federals by asking for safe passage to Canada. The following day, General Fitz Lee wrote his final dispatch to Robert E. Lee, commending each of his staff officers “and Captain Llewellyn Saunderson, who, having just arrived from his native country, Ireland, joined me previously to the fall of Petersburg, and remained with me to the last.”

38.4

27

Lincoln’s train had reached Albany, the state capital of New York, when Joe Johnston surrendered his army to Sherman on April 26. The one important difference to the terms that Grant had offered Lee was Sherman’s agreement to provide transport for the Southern troops from distant states. Henry Feilden had only a hundred miles to travel in order to reach Julia in Greenville, South Carolina, so he set off on his own horse.

I have not heard anything about you for so long that I have been quite miserable. You are aware I suppose that the war has ended in this part of the country, and that we have given in on this side of the Mississippi. Considering the position we were in, General Johnston made excellent terms with Sherman for the army—that is to say—that we are not to be molested by the Yankee Government, and our personal property is respected. No one else in the country has any guarantee for either life or property, except from the magnanimity of our enemies, which does not amount to much. The feeling of indignation in the North against our late leaders is described by the Yankee officers as intense. General Schofield (a very old friend of General Hardee’s) who now commands North Carolina advised him to leave the country at once. My own opinion is that our prominent men will be treated with great severity, if not executed.… The death of Lincoln was looked upon by our army as a great misfortune for the South. If he were alive we should have had no difficulty in getting terms.

28

The flight of John Wilkes Booth, the man behind the South’s “great misfortune,” also came to an end on April 26. (Lewis Powell, the attempted murderer of Seward, had been caught ten days earlier.) Booth and another accomplice were found in a barn a few miles south of Port Royal, Virginia, by a detachment of twenty-six Federal soldiers. When Booth refused to surrender, they set fire to the barn in the hope of flushing him out, but one of the soldiers, Boston Corbett, shot him in the neck while he remained inside. Corbett’s desire for glory deprived the mourning nation of the chance to obtain justice for its slain president.

Lincoln’s funeral train finally reached its destination at Springfield, Illinois, on May 3, 1865. After a twelve-day journey through more than 440 cities and towns, the bodies of Lincoln and his son Willie, who had died in 1862, would now be laid to rest in Oak Ridge Cemetery.

—

England was already “staggering,” according to Benjamin Moran, over the news of Lee’s surrender when the telegram announcing the assassination of President Lincoln arrived on April 26. John Bright felt “stunned and ill” when he heard the news. He was in mourning for his best friend, Richard Cobden, who had died on April 2, three weeks too soon to celebrate “this great triumph of the Republic,” and his brother-in-law Samuel Lucas, the owner and editor of the

Morning Star,

who had died on the sixteenth. “I feel at times as if I could suffer no more and grieve no more,” wrote Bright in his diary. “The slave interest has not been able to destroy the nation, but it succeeded in killing the President.”

29

“I was horror struck,” recorded Moran, “and at once went up with Mr. Alward [the new assistant secretary] to announce the intelligence to Mr. Adams. He turned as pale as death.” Within a few hours the legation was overrun with visitors. Adams had expected to see Bright and Forster, and possibly Lord Houghton (formerly Richard Monckton Milnes), but certainly not the Duke of Argyll or Lord Russell, who showed “as much sympathy as he was capable of.”

30

Lord Lyons also made a special trip to London to pay his respects and obtain news about Seward.

The British press was united over the tragedy of Lincoln’s violent death. Newspapers that had routinely criticized the president during his lifetime rushed to praise him. On April 28 and again on May 1,

The Times

printed long eulogies to the late president. “The feeling which the death of Mr. Lincoln has excited in England is in no degree confined to the advocates of the Northern cause, it has shown itself just as strongly among the friends of the South,” the paper declared. “We feel confident that a sorrow in which both nations may without exaggeration be said to share cannot pass without leaving them better acquainted with each other, and more inclined to friendship … than they were before.”

38.5

This was a wild hope, and the editors knew it; William Howard Russell could not help writing smugly in his diary: “Had

The Times

followed my advice how different our position would be—not only that of the leading journal but of England!”

31

Despite being the primary instigator and cause of

The Times

’ wildly biased reporting of the war, Francis Lawley escaped vilification because he was not a journalist by profession. The paper’s New York correspondent, Charles Mackay, on the other hand, was castigated for betraying his trade. The

Spectator

accused him of doing “probably more than any other single man to diffuse error concerning the great issue involved, and to imperil the cause of human freedom.”

32

The Times

’ managing editor, Mowbray Morris, belatedly realized the damage caused to the paper’s reputation by its pro-Southern reporting and dismissed Mackay from his post in a scathing letter that laid the entire blame for

The Times

’ position on his shoulders alone.

The Economist

also felt obliged to explain away its previous condemnations of Lincoln, claiming that over the past four years “Power and responsibility visibly widened [Lincoln’s] mind and elevated his character.”

33

But it was

Punch

that performed the greatest volte-face. Three weeks earlier, on April 8, the magazine had placed Lincoln in a gallery of April Fools that included Napoleon III and the MPs Roebuck, Bright, and Disraeli. The combination of embarrassment, shame, and shock that Lincoln was killed while watching his play moved Tom Taylor, the magazine’s senior contributor, to browbeat his colleagues into giving him a free hand to compose an abject apology and homage to the late president. The editor, Mark Lemon, supported him, telling the staff, “The avowal that we have been a bit mistaken [over Lincoln and the war] is manly and just.” Taylor did not hold back: “Between the mourners at his head and feet, Say, scurril-jester, is there room for you?” he asked contritely. Lincoln “had lived to shame me from my sneer, / To lame my pencil, and confute my pen, / To make me own this kind of prince’s peer, / This rail-splitter a true-born king of men. / My shallow judgment I had learned to rue.”

34

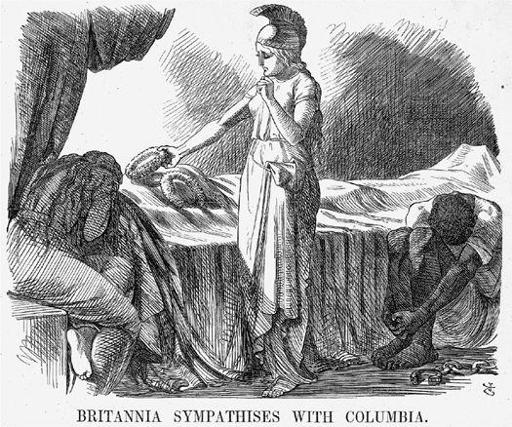

Ill.61

Britannia sympathizes with Columbia, Punch, May 1865.

Moran’s usual cynicism was temporarily overcome when he attended a mass meeting at St. James’s Hall, Piccadilly, on April 30:

The room was draped in black and three United States flags were gracefully entwined in crape at the east end of the room. The floor, the balcony, the galleries, and the platform of the great hall were literally packed with ladies and gentlemen.… The warmth of the applause, the earnest detestation of the murder, and the condemnation of slavery made me inwardly vow that hereafter I would think better of the feelings entertained towards us by Englishmen than ever before. And that if ever any chance of quarrel should occur between the two Countries, and I should hear an uniformed countryman of mine denouncing honestly and mistakenly, the spirit of England towards us, the recollection of what I saw then would nerve me to declare that we had friends in England in our day of sorrow, whose noble sympathy should make us pause.

35

He wrote even more fulsomely the following day after observing the speeches in the House of Commons and the House of Lords.

The U.S. consuls described extraordinary scenes at public meetings. A resident of Liverpool, arguably the most pro-Southern city in Britain, recorded with surprise that the news “has turned all sympathy towards the North. Immense meetings on the subject have been held almost everywhere in England and the Queen herself has addressed a letter of condolence to Mrs. Lincoln.”

36

Adams began to think that Lincoln had done more for Anglo-American relations by his death than by any other act during his life.

The great change in attitudes toward the North did not mean that the Confederates in England were being cast aside by their friends, however. James Spence disbanded the pro-Southern associations, because, he explained to a former member, it would be wrong to continue public action on behalf of the South: “I feel, too, that Englishmen cannot now take further part in this direction with propriety.” But his personal loyalty to Mason was undiminished, and he was among those who offered to establish a subscription fund on the Confederate agent’s behalf. (The Southern commissioner was too proud to accept such charity.) “The British believe that resistance is hopeless,” Mason wrote to Judah P. Benjamin on May 1, “and that the war is at an end—to be followed, on our part, by passive submission to our fate. I need not say that I entertain no such impression, and endeavor as far as I can to disabuse the public mind.”

37

The South’s other chief agents in England—James Bulloch, Henry Hotze, Colin McRae, and Matthew Maury—were far more realistic. Hotze trimmed his staff on the

Index

and began looking for financial backers, announcing that journal’s new cause would be the protection of “white man’s government” against the “Africanization” of America.

38

Maury sent a formal letter of surrender to the U.S. Navy, promising to desist from all acts of aggression against the United States. Bulloch and McRae girded themselves for prolonged litigation from creditors both real and predatory on account of the Confederacy’s unpaid bills. (Some firms, such as the London Armoury Company, which had turned away business in order to fulfill its lucrative orders from the Confederacy, would quickly go bankrupt.) The certainty that an investigation into their books would absolve them of wrongdoing counted for little against the knowledge that their personal sacrifices for the South had been to no avail.

John Slidell wrote to Mason from Paris urging him to open his eyes to the South’s defeat: “We have seen the beginning of the end. We are crushed and must submit to the yoke. Our children must bide their time for vengeance, but you and I will never revisit our homes under our glorious flag.”

39