A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (38 page)

Read A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War Online

Authors: Amanda Foreman

Tags: #Europe, #International Relations, #Modern, #General, #United States, #Great Britain, #Public Opinion, #Political Science, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #19th Century, #History

If the Yankees are worth their salt, they will at once make peace with the South and pour 100,000 men into Canada where they can easily compensate themselves for their losses of the Confederate states, and England be perfectly unable to prevent it. Unless the British Government at once make up their minds to fitting out an expedition which can start (as soon as war is declared) to seize Portland, and open up the railway communication from there to Quebec, I cannot see how we are to maintain our position in Canada this winter.

33

Lord Stanley went down to Southampton to see his son off. Lady Stanley was too distraught and remained in London. The navy did not have the eighteen troopships on hand to transport the 11,000 soldiers who were going to Canada in the first wave. Jonny’s vessel, the

Adriatic,

had been purchased from an American shipping firm and refitted in such haste that the U.S. flag could still be seen on the paddle box. As the

Adriatic

passed the

Nashville

on Southampton Water, the Guards band started to play “I’m Off to Charleston.” This cheeky act of bravado elicited a few halfhearted cheers from relatives who had gathered on the banks to wave farewell.

34

“It will be very cold in Canada and I am afraid Jonny will feel it,” Stanley wrote to his wife.

35

Their son was sailing at a dangerous time. Ice was beginning to close Canada’s navigable rivers, and monster storms would soon lash her seas.

36

“The all engrossing question is will America be foolish enough to go to War with us,” wrote James Garnett, the owner of a large mill in Clitheroe in Lancashire. “Many people think it will.”

37

Yancey and Dudley Mann fervently hoped so. They had not wasted any time in presenting Lord Russell with a letter of protest, and they had followed up two days later, on November 29, with a list of ships that had slipped through the blockade since April. Here was proof, they had argued, that the Northern blockade was ineffective and therefore not binding on neutral countries. Russell’s cold response on December 7 left them temporarily crushed, until they reflected on the thousands of British soldiers who were leaving for North America. This was a case, they decided, of actions speaking louder than words.

—

Charles Francis Adams was both furious and humiliated that his knowledge of the

Trent

affair was no better than what a reader could glean from

The Times.

“Mr. Seward’s ways are not those of diplomacy,” he wrote bitterly on December 9. “Here have I been nearly three weeks without positively knowing whether the act of the officer was directed by the govt or not.”

38

Henry Adams was equally indignant. “What Seward means is more than I can guess,” he told his brother Charles Francis Jr. “But if he means war also, or to run as close as he can without touching, then I say that Mr. Seward is the greatest Criminal we’ve had yet.” The seizure had undone all his father’s hard work. “We have friends here still, but very few. Bright dined with us last night, and is with us, but is evidently hopeless of seeing anything good.… My friends of the

Spectator

sent up to me in a dreadful state and asked me to come down to see them, which I did, and they complained bitterly of the position we are now in.”

39

Henry was not exaggerating the difficulties confronting Northern supporters. William Forster lamented to his wife that his efforts for peace resembled “the struggles of a drowning man.”

40

John Bright was at first too nervous to speak about the

Trent

affair, explaining apologetically to Adams that since his opposition to the Crimean War he had lost his appetite for being a national hate figure. Given Bright’s violent rhetoric, Adams rather hoped that this was true. Unfortunately, Bright overcame his fears and made a speech in Rochdale on December 4 that blasted the country for not being sufficiently pro-Union. This was too much even for the

Spectator,

which accused Bright of being prepared to sacrifice any principle if it did not sit well with America.

41

Harriet Martineau was one of the few English writers who could write with authority, since she was personally acquainted with Captain Wilkes, and even she was careful in her choice of words. Wilkes was not, she stressed in her articles for the

Daily News,

an Anglophobe or a warmonger, “but he lacks judgement and knowledge.”

42

Benjamin Moran realized the extent of the feeling against the North when he chanced to look out the window of his taxi and see that the American owners of the Adelphi Theatre had added the Confederate flag next to the usual Stars and Stripes. “The sight of this base emblem of slavery, treason and piracy made me ill with rage,” he wrote in his diary.

43

The Confederates and their supporters were also putting up posters in railway stations and distributing rebel banners to street hawkers. Hackney cabs were given miniature Union Jacks crossed with the Confederate flag.

44

Moran heard that such overt displays of Confederate sympathy were even more prevalent in Liverpool. The new consul, Thomas Haines Dudley, reported that Southern exiles living in the city were gleefully capitalizing on the

Trent

incident.

Although Moran longed to have an American representative in the country who would not be afraid to engage with the press, he regarded Thurlow Weed’s arrival on December 2 as a mixed blessing. “This morning’s

Times

contains a letter from Thurlow Weed defending Mr. Seward,” wrote Moran in mid-December. “The letter is strong in some things, but weak in others and

The Times

assails its vulnerable points with its usual malignity.”

45

Until the

Trent

affair, Weed had been in France working with Henry Sanford on schemes to influence European opinion.

Seward’s idea to send the three emissaries—Archbishop John Hughes, Bishop Charles McIlvaine, and Thurlow Tweed—“seems to me of no value,” Charles Francis Adams had written frankly to Edward Everett. But Weed disagreed; when he arrived at the U.S. legation on December 6, his first thought was that he should have come earlier. There was a general air of disarray about the place. The misfits in the basement made him wonder how business was done, while upstairs, Charles Francis Adams was in an alarming state: bewildered and angered by Seward’s silence, paranoid about England’s intentions, and mentally more than halfway home.

46

Weed immediately sent out letters and left his cards in all the great houses of London. The relative ease with which he connected with “intelligent and influential English friends of the North” led him to suspect that Adams had not tried very hard to penetrate society. Weed was able to arrange an interview with Lord Russell and had a perfectly sensible, albeit noncommittal, conversation with him. Although he did not say it in so many words, Weed was appalled that Adams had allowed Seward to become so thoroughly feared and hated.

47

“You have been infernally abused, and are wholly misunderstood here,” Weed told Seward. Everyone he met believed that the secretary of state was determined to have a war. This was true even of Seward’s friends. Lady Napier unhappily related to Weed a remark Seward had made just before their departure from Washington. “On some occasion,” wrote Weed, “you talked about the incoming Administration going to war with England; that subsequently when alone with you, she asked, ‘Why do you talk about war with England?’ and that you replied seriously, ‘that it was the best thing that could happen for America.’ ”

48

More damning still,

The Times

printed the story of his “joke” to the Duke of Newcastle, during the Prince of Wales’s tour of America in 1860, that when in power he would manufacture a quarrel with England.

49

It was already midnight on December 10 when Thurlow Weed sat at his desk to compose one of the most serious letters he had ever written to his friend. “I have finally got Lord [

sic

] Newcastle’s own version of what was said to him,” he wrote; “whatever you did say—was said. This, with the allusions to Canada … is regarded as evidence of your determined enmity to England, and even the Friends you made here—many of whom I have met—are carried away by this idea. And consequently War, unless you avert it, is inevitable. I pray that I am not mistaken in the hope that you comprehend the disastrous effects of such a war.”

50

The days passed and still there was no word from Washington. Nothing, however, worried Weed so much as his friend’s silence. He sent a letter to Lincoln, imploring him to “turn the other cheek”; Adams sent yet another letter to Seward.

51

On December 14,

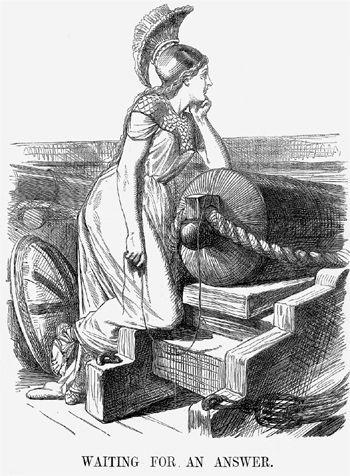

Punch

published a cartoon entitled “Waiting for an Answer,” which showed Britannia ready to fire a cannon. At the Foreign Office, Lord Russell continued to fret over whether they had made the right decision. Their dispatch to Lyons left no room to maneuver if Seward prevaricated or refused point-blank. But “I do not think,” wrote Russell, “the country would approve an immediate declaration of war.” A “peace meeting” at Exeter Hall in the Strand had attracted four thousand people. Russell asked Palmerston if they should give the United States a second chance, should the worst happen, so long as Seward’s letter was a “reasoning, and not a blunt answer.”

52

Ill.12

Britannia ready to fire, Punch, 1861.

On Monday, December 16, London was plastered with black-bordered announcements of Prince Albert’s death. He had died at eleven o’clock on Saturday night. Moran knew about the prince’s alteration of the cabinet dispatch to Lord Lyons, and though he feared his action could be misinterpreted, he went defiantly to Buckingham Palace and signed his name in the condolence book. For good measure he added the names “Mr. and Mrs. Adams” next to his own. Late that same night, a messenger arrived with a dispatch from the State Department. The letter was short, too short considering the nature of the crisis, but it did contain Seward’s admission that Wilkes had acted “without any instructions” as well as the remark that the American government hoped that London would “consider the subject in a friendly temper.” Adams thought this “was not discouraging” but hardly a clear endorsement for peace. He wondered whether it was even worth showing to Lord Russell. Alarmed by this untimely display of diffidence, Moran and Wilson pleaded with Adams to go to the Foreign Office. Troopships were still departing for Canada and time was running out.

—

The British lion had turned tail, or so Washington thought during the first week of December. Mercier’s execrable English created such confusion that Lincoln came away from their conversation believing that the British minister had given Mercier good news about England, and that Britain’s law officers saw nothing wrong in the commissioners’ seizure. “There would probably be no trouble about it,” Lincoln cheerfully asserted to his friend Senator Orville Browning after the meeting.

53

Lincoln was also being misled by Charles Sumner, whose straightforward and sensible position on the

Trent

had become infected by his craving for popularity. At the beginning of the crisis, Sumner had assured the Duchess of Argyll that he would do everything in his power to resolve “any ill-feeling between our two countries.”

54

But after he saw Lincoln on December 1 and realized that the president had no desire to release the prisoners, he abandoned his original position and suggested that they turn the case over to international arbitration. The plan protected the United States’ pride and salvaged Sumner’s; he had not been consulted or included in any of the cabinet discussions about Captain Wilkes. Sumner had no hesitation about blaming Seward: “The special cause of the English feeling is aggravated by the idea on their part that Seward wishes war, they say—‘very well—then we will not wait,’ ” he told a friend in New York. “If the [British] Govt & the people could be thoroughly satisfied of the

real good will

of this Administration, a great impediment to Peace would be removed.” That impediment, of course, was Seward.

55