A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (42 page)

Read A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War Online

Authors: Amanda Foreman

Tags: #Europe, #International Relations, #Modern, #General, #United States, #Great Britain, #Public Opinion, #Political Science, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #19th Century, #History

Lord Lyons wished in his heart he could escape while there was relative calm. “I don’t expect to be ever free here from troubles,” he wrote.

29

There would always be another incident. “I have no doubt that for me personally this would be the moment to give up this place. I can never keep things in as good a state as they are,” he confided to his sister two days after the ball. “However, I cannot propose this to the Government, especially after the GCB—and of course feel bound to stay as long as they wish to keep me.”

30

Lyons was referring to the Order of the Bath, which Lord Russell had arranged to have bestowed upon him for his handling of the

Trent

crisis. When he had learned of the honor, Lyons had written to Russell with his characteristic humility that he had done nothing “brilliant or striking;” “the only merit which I can attribute to myself is that of having laboured sedulously, though quietly and unobtrusively … to carry out honestly your orders and wishes.”

31

He also commended his staff for their exemplary behavior during the crisis—although he would not have been able to say the same for them now. Since the resolution of the affair, the attachés and secretaries had been living up to their nickname of “the Bold Buccaneers.” Two of the more literary members of the group had decided to put on a play, and persuaded Lyons to allow them to perform it at the British legation.

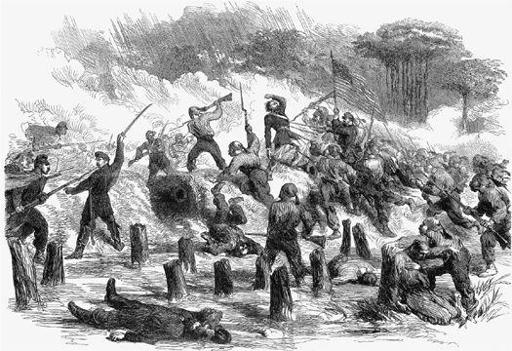

Ill.16

The 9th New York Volunteers (Hawkins’s Zouaves) and the 21st Massachusetts in a bayonet charge on the Confederate fieldworks on Roanoke Island, by Frank Vizetelly.

The attachés’ youth and high spirits insulated them from the subdued atmosphere that pervaded Washington after the sudden death of Lincoln’s middle son, Willie, on February 20. The precocious eleven-year-old, who had reigned as the undisputed favorite of the family, was suspected to have died of typhoid fever. Mary Lincoln withdrew into her own private agony of grief, leaving her devastated husband with the burden of caring for their other boy still at home, seven-year-old Tad, who was battling the same illness that had killed his brother. The

Spectator

’s correspondent Edward Dicey was introduced to Lincoln not long after Willie’s funeral and noted the “depression about his face, which, I am told by those who see him daily, was habitual to him, even before the recent death of his child.” During their short interview Lincoln earnestly interrogated him about English public opinion. “Like all Americans,” commented Dicey, he “was unable to comprehend the causes which have alienated the sympathies of the mother country.”

9.1

32

The same question about England’s sympathies was being asked in the South. “Seward has cowered beneath the roar of the British Lion,” bemoaned John Jones, a clerk in the Confederate War Department. “Now we must depend upon our own strong arms and stout hearts for defense.”

33

Even the shrewd and unflappable diarist Mary Chesnut had given in to her optimism during the

Trent

affair. For a brief moment she had shared the belief so prevalent in the South that the Royal Navy would appear off the coast and blow the blockade to smithereens. Now she wondered if the British were laughing at them, “scornful and scoffing … on our miseries.”

34

Despite the brouhaha over their release, she feared that Commissioners Slidell and Mason were chasing a chimera. “Lord Lyons has gone against us. Lord Derby and Louis Napoleon are silent in our hour of need,” she wrote. The loss of Roanoke and the forts in Tennessee caused an uproar in Richmond. Someone had to bear the blame for these dreadful and unexpected defeats, and who better than the Confederate secretary of war, Judah Benjamin? “Mr. Davis’s pet Jew,” as his critics called him, was accused of having sacrificed Roanoke Island by refusing to send reinforcements. Benjamin’s stint at the War Department had been hampered from the start by his lack of rapport with the military, and this latest crisis would make his position untenable. However, the truth in the case of Roanoke, which out of loyalty he never revealed to Davis, was that there were neither arms nor men to spare.

35

Two or three arms shipments a month from England were not enough to maintain one army, let alone several across hundreds of miles.

—

The freedom experienced by the four ex-prisoners on board HMS

Rinaldo

as she crossed the Atlantic in early January was far worse than the dull confinement the Confederate commissioners had endured at Fort Warren. To walk on the icy deck was to risk a thousand deaths. Huge icicles dangled above their heads. Any person not wearing a safety rope was liable to slip or be blown out to sea. Before the journey’s end, many of the sailors had suffered frostbite. “If you have no news of ‘Rinaldo,’ I fear she is lost—horrible to think of,” William Howard Russell wrote to Delane on January 16. Horrible but somehow not unexpected, considering the appalling misfortunes that had already blighted the Southerners’ mission.

36

“Mr. Slidell,” declared a Northern journal, “is the ideal of a man who would think it a privilege to get into a scrape himself, if he could only involve his host and patron too.” Mr. Mason, on the other hand, was “more of a bull-dog, ready to fasten on friends and foes alike.”

37

Yet, until the

Trent

affair, there had been nothing in their previous histories to suggest that either James Murray Mason or John Slidell was the type of man whose fate would move armies. They so neatly fitted into Southern stereotypes as to be walking caricatures of a Virginia aristocrat and a Louisiana politician. Mason, who had been brought up amid elegant surroundings and liveried servants, could trace his family back to the English Civil War, in which one of his Cavalier ancestors commanded a regiment at the Battle of Worcester. Slidell, on the other hand, was the son of a moderately successful New York candle maker who had fled the city after a scandal involving a pistol fight and reinvented himself as a successful lawyer in New Orleans.

38

Slidell had few hatreds, but one of them was for New Yorkers who refused to forget his humble beginnings.

39

He was happier in New Orleans, where he could lift his finger and see his puppets raise their hands.

William Howard Russell had met both men and found them tolerable. Mason was tall, heavyset, and crowned with a bouffant hairdo that was once leonine but had started to recede into a mohawk. His bright blue eyes and ruddy cheeks made him appear kindly, but out of his small, thin mouth came the most unashamedly racist and proslavery statements Russell had ever heard. His proudest achievement up to this point had been the drafting of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, which denied escaped slaves any place of sanctuary in the United States. Mr. Mason, Russell informed readers of

The Times

on December 10, “is a man of considerable belief in himself; he is a proud, well-bred, not unambitious gentleman, whose position gave him the right to expect high office,” though, as would become apparent, not necessarily the talent. His ten years as chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee had left no discernible trace of experience on him. Mary Chesnut considered him to be one of the bigger imbeciles among her acquaintances: “My wildest imagination will not picture Mr. Mason as a diplomat,” she had written after hearing of his appointment. “He will say ‘chaw’ for ‘chew,’ and he will call himself ‘Jeems,’ and he will wear a dress coat to breakfast. Over here, whatever a Mason does is right in his own eyes. He is above law.” Mary knew the English horror of tobacco chewing, too. “I don’t care how he pronounces the nasty thing but he will do it,” she wrote. “In England a man must expectorate like a gentleman if he expectorates at all.”

40

This last observation was certainly true, and it would count against Mason almost as much as his passionate belief in slavery.

41

By contrast, “Mr. Slidell,” Russell wrote in his diary, “is to the South something greater than Mr. Thurlow Weed has been to his party in the North.” Like Mason, he was tall and well built, but feline rather than bluff with “fine thin features, [and] a cold keen grey eye.”

42

His French was excellent, thanks to his Creole wife, as was his taste in wine. His suave manner was the antithesis of Mason’s chomping heartiness. “He is not a speaker of note, nor a ready stump orator, nor an able writer, but he is an excellent judge of mankind, adroit, persevering, and subtle, full of device, and fond of intrigue … what is called here a ‘wire-puller.’ ”

43

He could destroy a man or make him, as he did Judah Benjamin, who owed his entire political career to Slidell’s connections. If the attainment of power was a belief, then Slidell was a practicing zealot. On all other questions he was agnostic. Slidell’s urge to politick was so great, wrote Russell, that if he were shut up in a dungeon he “would conspire with the mice against the cat rather than not conspire at all.”

44

The Confederates arrived in England on January 29 to little fanfare. The press, including

The Times,

had warned the country against turning them into heroes; the Confederate commissioners were representatives of a government that was waging an undeclared war against Britain’s cotton industry. Mason asked his friend William Gregory, MP, whom he had not seen since Gregory’s visit to Washington in 1859, whether British resentment of the cotton embargo was the reason for the “harsh” treatment meted out to the

Nashville

and Captain Pegram, who had been forbidden to make any military alterations to his ship or stay longer once his repairs were completed. Gregory told him that, on the contrary, this was in accordance with the neutrality proclamation.

The

Nashville

set sail from Southampton on February 3, cheered on by thousands of well-wishers. (William Yancey’s departure, on the same day but in a different ship, went unremarked.) With her Confederate flags and black-painted hull, the ship managed to look warlike and dashing at the same time. HMS

Shannon

—with gun ports open and engines running—stood guard between the

Nashville

and

Tuscarora.

There could be no engagement between the warring vessels in British waters. Much to Captain Craven’s chagrin, the

Tuscarora

would have to wait twenty-four hours before she could begin her pursuit of the

Nashville.

9.2

Unbeknown to Captain Robert B. Pegram, a young man who called himself Francis Dawson had joined the crew under false pretenses as its fifty-first member. Pegram had thought he was dealing with a boy of sixteen or seventeen when Dawson first asked to come on board. He offered him a position “as a sailor before the mast,” meaning the lowest rank of seaman, and assumed that this would be the last he saw of him. Dawson boarded the ship with the help of one of the master’s mates. But he was no teenage runaway; he was in fact a twenty-one-year-old who had failed to break into the theater as a playwright and was looking for a new occupation. His real name was Austin Reeks; his father had ruined the family through one idiotic financial speculation after another, leaving his mother dependent on the charity of relatives. A widowed aunt who paid for Austin’s education was the inspiration for his new name: Francis Warrington Dawson. Mrs. Dawson’s late husband, William Dawson, had been an officer in the Indian Army. The change of identity and the leap into an adventure was not untypical behavior for Austin. He had never wanted to be himself, living in poverty with a father who made him ashamed and a mother he pitied. “My idea simply was to go to the South, do my duty there as well as I might, and return home to England,” Dawson wrote in his reminiscences. One of his great strengths was that he believed his own stories. Once he had claimed that he was motivated to fight for the South by idealism, it became true.

He needed every shred of his sense of duty to survive his difficult initiation into life at sea. On his second day, Dawson’s trunk was broken open and his belongings stolen. The old sea hands disliked the interloper who spoke fine English and said his rosary at night. They resented even more his obvious rapport with the ship’s officers, and they punished him with the worst jobs. After nearly three weeks of hazing from the crew, Dawson decided that his life was “truly a hard one. I could not have borne it but that I know how judicious is the step I have taken.… Time does not in the least reconcile me to the men in the forecastle! More and more do I detest and loathe them.” Fortunately, once Captain Pegram discovered Dawson’s presence, he took pity on him and gave orders for his bunk to be moved to the upper deck. He soon felt an avuncular concern for the impetuous youth and was overheard saying that he would do something for Dawson once they reached home. Dawson hoped so. “I am told that I may make a fortune in the South if I chose,” he wrote his mother. “God grant that I may for your sakes.”

45