A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (45 page)

Read A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War Online

Authors: Amanda Foreman

Tags: #Europe, #International Relations, #Modern, #General, #United States, #Great Britain, #Public Opinion, #Political Science, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #19th Century, #History

Bulloch had taken a gamble by sending the

Florida

off without arms or a proper crew. Although the captain, James Duguid, knew the truth, since he was William Miller’s son-in-law, the rest of the English crew had been told they were bound for Palermo. Bulloch was relying on John Low, a Scotsman who had emigrated to the South in his early twenties, to protect his investment. Low was traveling on the

Florida

as a passenger, though in reality he had command of the vessel. His orders were to have the

Florida

delivered to Nassau in the Bahamas, where he was to hand the ship over to Lieutenant John N. Maffitt (whom Bulloch knew well and believed was resourceful enough to know what to do with her) or, in his absence, to any Confederate officer.

Thomas Dudley was convinced that the Liverpool customs officers had dragged their feet during the investigation into the

Florida.

A report in late March that the U.S. Navy had captured Captain Pegram and the

Nashville

off the coast of North Carolina cheered the Federals a little but did not lessen their sense of grievance against the British authorities, whom they suspected of ill-concealed bias toward the South. Adams went to see Lord Russell on March 25 to protest against England’s laxity over Confederate violations of the Foreign Enlistment Act. Russell listened sympathetically until Adams’s indignation took on such a strident tone that he undermined his case. “Adams has made one of his periodical blistering communications about our countenancing the South,” reported an internal Foreign Office communiqué after the meeting.

14

Russell found the American minister’s charge of bias especially unfair after the British government’s myriad concessions to the North, not least its propping up the shaky legal foundations of the blockade.

15

Their relations deteriorated further after Adams complied with Seward’s instruction to remonstrate once more against Britain’s declaration of belligerency. This was not some “local riot” of twelve months’ duration, expostulated Russell. Furthermore, he complained, when it came to blockade violations, why was Britain always being made out to be the villain when other nations were following the same practice?

16

Ironically, while Adams was accusing Lord Russell of being insincere, the French emperor was playing a multiple hand between his own ministers and the rival American camps. Much to the annoyance of everyone except the Confederates, Napoleon held several private interviews in April with William Schaw Lindsay, MP (who was also a shipping magnate). Lindsay had played a significant role during Anglo-French negotiations of the 1860 trade treaty and was easily able to gain an audience with the emperor without exciting the suspicion of the British embassy. Napoleon said everything Lindsay wished to hear.

17

John Slidell’s spirits soared when Lindsay reported back to him. “This is entirely confidential,” he wrote to James Mason in London, “but you can say to Lord Campbell, Mr. Gregory etc. that I now have positive and authentic evidence that France only waits the assent of England for recognition [of the South] and other more cogent measures.”

18

Russell was so annoyed by Lindsay’s interference that he refused to meet him when the MP returned to England. The Confederates were elated, however, by the news from France; Consul Morse reported to Seward that the “Rebels here confidently predict two or three great Southern victories and the recognition of the Confederate States before the adjournment of Parliament.”

19

—

The commencement of Parliament had brought with it the resumption of Lady Palmerston’s “at homes.” Neither James Mason nor Henry Hotze was on the guest list, but Benjamin Moran was able to finagle an invitation for himself, Charles Wilson, and Henry Adams. He was one of the first guests to arrive at Cambridge House on March 22 and spent the early part of the evening gawking at his surroundings. The “drawing rooms are not so large as one might expect,” he pronounced, but they were brilliantly lit for the occasion, and as more people entered they “began to assume an animated and even gorgeous appearance.”

20

Too shy to speak to strangers, he hovered in corners and by tables. Henry Adams, on the other hand, arrived determined to make this his entrée into society. He longed to be friends with “Counts and Barons and numberless untitled but high-placed characters.”

21

Henry just hoped that the “unfortunate notoriety” caused by his caustic comments on English high society in “A Visit to Manchester” had been forgotten in the intervening three months. At the foot of the lofty staircase he gave his name to the footman, only to hear it called up as “Mr. Handrew Adams.” He corrected him and the footman shouted loudly, “Mr. Hantony Hadams.” “With some temper,” Henry corrected him again, and this time the footman called out, “Mr. Halexander Hadams.” Henry accepted defeat and “under this name made [my] bow for the last time to Lord Palmerston who certainly knew no better.”

22

After this painful event, Henry decided it was not worth trying to storm the social ramparts of 94 Piccadilly.

“I have no doubt that if I were to stay here another year, I should become extremely fond of the place and the life,” Henry mused to his brother Charles Francis Jr. on April 11. But for now he had a “greediness for revenge.” He approved of the chief’s “putting on the diplomatic screws.” England should not be allowed to wriggle out of her responsibility for aiding the Confederates. At least the

Nashville

“has been taken or destroyed,” he added. Moreover, it turned out that the

Harvey Birch,

which Confederate captain Pegram had triumphantly claimed as his first capture, belonged to Confederate sympathizers. Writing on the same day, Bulloch warned the Confederate secretary of the navy, Stephen Mallory, that Pegram’s mistake had caused them considerable embarrassment. Indiscriminate attacks on Northern ships were perhaps not the best method of waging war.

23

Despite Charles Francis Adams’s complaints to Russell, Bulloch knew better than anyone else the truth about the British government’s intentions. It “seems to be more determined than ever to preserve its neutrality,” he wrote in disappointment; “the chances of getting a vessel to sea in anything like fighting condition are next to impossible.” The fate of his prize cruiser under construction, Lairds’ Project No. 290, now preoccupied him. He had her moved to a private graving dock, where she would be masted and coppered out of sight of prying eyes. But with the

Nashville

captured and the

Florida

sailing off on a blind adventure, defenseless and without a real crew, Bulloch was beginning to wonder whether they were pursuing the right course of action. His anxiety was, for the moment, misplaced. Three days later, on April 14, Benjamin Moran recorded in shock: “It seems as though the

Nashville

was not captured at Beaufort, N.C., but escaped. This is one of the most mortifying events of the war to us. Our naval officers on the sea-board have covered themselves with disgrace.”

24

—

“I cannot say that my value as a sailor had increased materially during the voyage,” wrote Francis Dawson after the

Nashville

arrived at Morehead City, North Carolina, on February 28. He was so relieved to be on dry land that it hardly mattered to him that he was homeless and friendless. Captain Pegram departed for Richmond as soon as they docked, bearing boxes of much-needed supplies, including stamps and banknote paper. Dawson was left to find his own lodgings. “I had determined to take my discharge from the

Nashville,

and decide, by tossing-up, which one of the various companies named in the newspaper I should join.” Pegram, however, made good on his promise. “I also wish to call specially your attention to the sacrifices made by Mr. Frank Dawson,” he wrote to Stephen Mallory in early March. The “young Englishman” had “left family, friends, and every tie to espouse our cause,” and, “not to be put off by any difficulties thrown in his way, insisted upon serving under our flag, performing … the most menial duties of an ordinary seaman.”

25

On the strength of this recommendation, Dawson was appointed master’s mate, the lowest officer rank in the navy. Pegram personally gave him the news, “one furious cold morning,” while Dawson was “scraping the fore-yard, wet through with the falling sleet and intensely uncomfortable.”

26

Dawson’s orders were to report for duty at the Norfolk shipyard in Virginia. This was the same destination as Pegram, who was going to take command of a ship that was still in dry dock. “To crown my satisfaction,” Dawson recorded, “Captain Pegram told me that he intended to make a visit to his family, in Sussex County, Virginia, and would be glad if I should accompany him, and remain with him until it was necessary to go to Norfolk.” They left Morehead on March 10 and took the train up to Virginia. The young man was fascinated by the alien landscape that rolled past his window; there were no neat hedgerows and green pastures filled with sheep, only mile after mile of scrub and woodland. Dawson’s short stay at the Pegrams’ plantation exceeded his wildest expectations. The family adored him, and local worthies hailed him as a foreign knight come to their rescue. Dawson was already a convert to the Southern cause; all the attention he received gave him personal as well as fanciful reasons to embrace the Confederacy. “You may rest assured,” he wrote earnestly to his mother, “that while one of her children has power to wield a sword or pull a trigger, the South will never desist from her struggle against the Northern oppressor.”

27

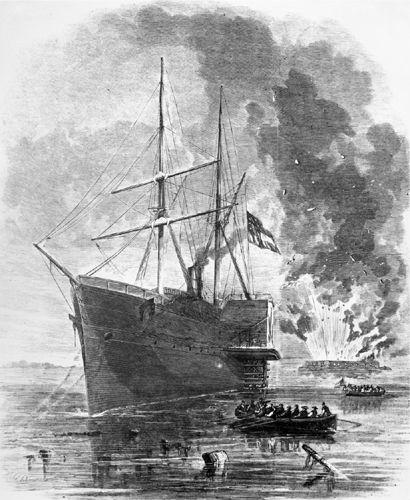

Ill.19

The Confederate steamer Nashville, having run the blockade, arrives at Beaufort, North Carolina.

On the day of Dawson’s departure, news reached the plantation of CSS

Merrimac

’s encounter with USS

Monitor.

The ships were the result of a frantic race between the North and South to construct the first American ironclads. The Confederates won (by twenty-four hours) when they launched the

Merrimac

(renamed CSS

Virginia

) on March 8, 1862. The vessel was an old U.S. warship that had been burned by Union sailors when they abandoned the Norfolk Navy Yard in Virginia the previous summer. Since then, the

Merrimac

had been completely remodeled except for her engines, which the Confederates had not had time to repair. Engineers literally “clad” the

Merrimac

in iron plates and added a ram to the stem of the ship. Long and squat, she looked more like an iron champagne bottle than a ship. Her speed was terrible, but the armor plating made her invincible. When the

Merrimac

slowly steamed into Hampton Roads to confront the Federal blockading fleet, nothing like her had ever been seen before. Hampton Roads is a wide body of water where three large rivers converge before flowing into Chesapeake Bay and out into the Atlantic. The Union navy had been in control of the bay and Hampton Roads for almost a year. Stephen Mallory knew that it was vital for the Confederacy that he take them back, and as the wooden Union gunboats fired ineffectively at the

Merrimac

’s hull, it seemed as though he would.

There was cheering in Richmond and hysteria in Washington after the battle. Lincoln called a special cabinet meeting at which the new secretary of war, Edwin Stanton, made a spectacle of himself, ranting that every city on the Eastern Seaboard would now be laid waste. The secretary of the navy, Gideon Welles, however, was unfazed. The newly clad and outfitted

Monitor

was already on its way to Hampton Roads, and he expected a more favorable outcome than the previous day’s rout. The secretary’s hopes were justified. The equally strange-looking Federal vessel, described by some as a “tin can on a shingle” (the tin can being a revolving turret that could fire in any direction), could not sink the

Merrimac,

but was powerful enough to pin her down. After four hours of point-blank firing, both ships withdrew, damaged but not inoperable. The possibility that the

Merrimac

might yet force its way to Washington had almost as powerful an effect on Edwin Stanton as the first Hampton Roads bombardment. To stop the Confederate monster, he wanted the main water channels to Washington blocked with sunken ships.