Adventure Divas (16 page)

Bedi stands and firmly shakes our hands. Her old wisdom and new tools will continue to tackle contemporary challenges, and I silently wish her well in the inevitable battles. She hunches slightly to put on her cap and then walks away, alone, through two perfectly aligned rows of trees. Their solid lower trunks are painted red, to prevent disease, and higher up, the branches shake freely in the wind.

TO:

H

OLLY

FROM:

J

EANNIE

SUBJECT:

E

MPIRE UPDATE

Michael is making good progress on recutting Cuba into two half-hour shows but will need some rewriting, direction, and rerecording from you. Site is good: Kate did a wonderful Eritrean homepage (with Jill’s profile of the war-poet), and Inga la Gringa ruffled feathers with her “How to get your sex toys past customs” column. Lotsa hits. Still working trademarks but we’ll need $$$$$. Are you interviewing the bandit?—Jeannie

The subject line of Jeannie’s e-mail and Bedi’s insights on humility and enlightened leadership have made me think a little harder about our Diva rhetoric. We’ve been playfully using terms like

empire

and

divadom

to make a point about corporate media and entertain ourselves, but there is the possibility that by wielding the master’s tools we would get cooties. Sometimes, the best way to fight fire is not with fire, but with water. Gandhi and other Indian leaders undermined the British army not through self-aggrandizement and armed struggle (the favored tactics of imperialists) but by changing the rules—by using self-restraint and nonviolence.

On our most idealistic, caffeinated days, we hoped we were, in our own small way, doing something in that spirit of originality. That is, by building an independent, uncompromising, pro-woman “empire,” we could create an alternative model to corporate-run media. And by highlighting and linking divas around the world, we could imagine new models of power, leadership, and—as important—individual potential.

But until we could figure out a way to get by without additional investor capital, and until we could dream up a new, nonimperialist rhetoric, we would just have to keep improvising.

“Okay, then, you must

all wear long-sleeve shirts and clean clothes,” says Raghu, an investigative journalist who is moonlighting as our fixer. Raghu is lanky and mustached; he speaks judiciously and wears unwrinkled collared shirts. Often pastels. Foreign-paid fixer fees in India are much better than local salaries, so we have been able to persuade Raghu to spend his vacation from his journalism job with us.

Raghu, no doubt, is secretly glad to have a legitimate opportunity to upgrade this underdressed crew (except Julie, of course). “You cannot show disrespect in the temples,” he says, glancing toward my threadbare 501s.

As we head toward the temple, Raghu uses his cell phone to call Phoolan Devi’s residence for the fourth time today. He has been calling her handlers repeatedly, trying to arrange for us to meet Devi. He has never received a yes; but then again, he has not received a no, either, so Julie and I encourage him to keep trying. Phoolan Devi is from a low caste of fishermen and, as is usually the case among the low castes, is illiterate and does not speak English, so Raghu (rather than any of us) must make the initial contact. Illiteracy might disadvantage Devi, but she is said to compensate for it in spades through cunning, smarts, and charm—skills that probably helped in her outlaw days. I must admit to a romantic fascination with this Robin Hood–like figure, who actually did steal from the rich and give to the poor. A legend in her own time, Devi is regarded by many as a champion of the lower castes.

The narrow street that leads to the Kali temple is lined with vendors in wooden stalls and crowded with beggars begging, goats bleating, incense burning, children playing, and hundreds of the faithful preparing to enter the temple. Unpleasant brass bells gong every few seconds. Vendors peddle offerings to be presented at Kali’s altar, as well as likenesses of the deity in 2-D, 3-D, plastic, wood, and porcelain; the street is filled with Kalis, large and small. I buy a garland of yellow marigolds for three rupees and continue on up the concourse of mayhem. Mounds of blood-red

kumkum

powder dot the way to the temple. I idly wonder if it is like a Grateful Dead concert where all the really interesting action happens in the parking lot or if this level of sensory orgy could be sustained inside the small, circular, white marble temple itself.

The moment I breach the entrance, I realize the latter is true. The interior of the temple pulses with Kali devotees boisterously doing

puja

(prayer). Throngs of people are tussling and pushing to get near a giant red poochy orb with a tree growing out of its top that anchors the center of the room. To my eye, the amorphous, globular manifestation of Kali (that looks nothing like the tchotchkes outside) is more curious than divine. People are rocking against and rubbing its marble base. Teenage boys bless worshippers by tapping their foreheads with a red cinder. Women bow, then dab cinders on their foreheads and down the parts in their long, pulled-back hair. Men sway, bellowing

puja

with their eyes closed. Bells clang mercilessly, erratically, as if to throw a wrench in the possibility of order, and sweet, sweet incense engulfs the entire overripe scene.

“Not exactly a Quaker meetinghouse,” John, our cameraman, says about the atmosphere he’ll be hard-pressed to capture on tape.

While the important blob might lack the features one might expect of a tough deity, the images of Kali that glare down from all 360 degrees

do not.

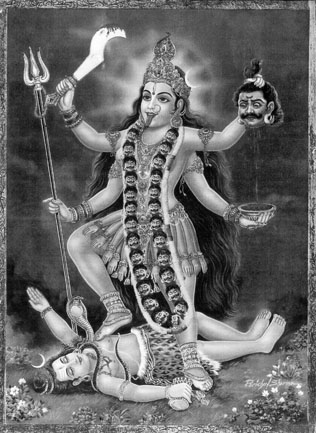

Yowza. This manifestation of the fearsome goddess has a red flailing tongue, dances with glee on the corpse of Lord Shiva, and shamelessly wears a garland of severed limbs and human heads that are dripping blood.

Kali

Goddess Kali, who is popular with the Bengali population, is believed to be a fierce, creative, and destructive manifestation of divine energy. Julie introduces me to a soft-spoken Bengali woman of about thirty-five who, with her family, tends the temple. She tells us that this ferocious deity that inspires so many signifies the divine and wicked forces within all of us. Kali’s skirt of severed limbs suggests the transitory nature of human values and signifies the slaying of evil (thus the need to be mighty ferocious). In short, Kali is harsh, but truthful. Devotion to her is supposed to reduce tension and fear—fear being one of the primary things she bravely slays.

The Bengali woman leads me up to the altar, and I feel bad because I get cuts in front of a real devotee who is twice my age and missing an arm. A young boy blesses me with a smudge of red

kumkum

on the forehead and tosses a woven, sparkly red cloth over my head. Being blessed in the name of a goddess who dangles bloody heads and severed limbs like charms on a bracelet is surprisingly . . . uplifting. Kali, like Cuba’s black Madonna, is much more exciting than Mary, whose lot in life always struck me as a bit dull. At least Kali gets to dance and slay things. Mary, in her time, was a maligned, celibate single mother. Need I say more?

At home I am comfortable with being fairly aspiritual; and while I’ll never get caught burying a placenta in my backyard, India is tweaking in me the possibility that I might be overlooking something

big.

The need for ritual, the want of existential explanations, the affirmation of common truths; I get the need for a spiritual life, but it’s the vehicle that always trips me up. Hinduism’s acceptance of all beliefs and forms of worship is by definition agreeable, and the sassy deities are more appealing to me than Christian martyrs. But, as I wade against a current of worshippers to get out of the temple, I conclude that India feels like a spiritual petri dish: rich with life’s delicious goop, but not something I’m entirely prepared to eat out of just yet.

I put my hand in my pocket to pay an eight-year-old boy for watching my flip-flops, which were bought at Target in Seattle but were made in India. Child labor, spiritual tourism, First World economic fascism, and simple gratitude all pass through my mind in the time it takes me to hand him the five rupees.

John and I climb to the roof of a building across the street to get a wide angle of the temple; I pull back a laundry line so he can get a clear shot. I smell blood and curry and feces and cooking animal flesh; I hear people wailing, and bells, and crying children and meditative chanting. Pure red and pure yellow and lots of gray, and so, so many people fill up this picture.

“Tape’s out,” says John, and we walk back down the stone staircase to the temple to find the rest of the crew. Raghu is sitting on a brick wall still holding his cell phone, looking more frustrated than ever. Apparently he has had another nonstarter conversation with Phoolan Devi’s people. “Politicians. They are the same all over the world,” he says about her elusiveness.

“We can’t give up,” I say.

“Are you sure?” he says. Raghu doesn’t think we should be pursuing Devi. He is less forgiving than I am of the murders Phoolan Devi committed during her tenure as a bandit.

Personally, I can’t resist the story of a low-caste woman who escapes a brutal child marriage to become a bandit, lays down her arms on her own terms, uses her populist power to negotiate the length of her prison term, and then goes on to become a member of Parliament.

Raghu can.

We have had this conversation before.

“But she was avenging her own

gang rape,

” I say, referring to a group of higher-caste village men she ordered killed several months after they tied her up and brutally gang-raped her in a barn

for a month.

Two cabs drop us

at the Delhi train station to catch the afternoon train to Jaipur, capital of the state of Rajasthan. We lug our equipment on board and buy chai from a nine-year-old boy who carries a mobile metal tea set lashed to the front of his body by a white cloth sling. Julie downs her fifth hot, sweet, milky tea shot of the day.

Somewhere along the way—be it by siding with a murderess, general sacrilege, or that somosa I bought and snarfed on the street—I must have derailed my karma because I spend most of the train ride to Rajasthan rushing to the six-inch hole in the floor of a stinky train car (the bathroom) that is servicing my wicked bout of Delhi belly. When I am not squatting in misery, channeling my secret happy place, or necking the Imodium Julie has given me, I wedge myself fetal in my train seat to read Elisabeth Bumiller’s

May You Be the Mother of a Hundred Sons: A Journey Among the Women of India.

The book confirms that the ladies in India could indeed use a few more anchors. For every Kiran Bedi, who has had the tools, education, and class standing to realize her power, there are thousands of Indian women who fare less well. Seventy-five percent of Indian women (that’s about 370 million) are illiterate and poor and live back-breaking rural lives.

Thousands of “bride burnings,” in which women are killed because their husbands or in-laws are unhappy with the dowry, take place every year. Female infanticide. Sex-selective abortion among the middle class. Child marriage. The depressing list goes on. I am beginning to understand the widespread appeal of Kali, an avenging female icon.

Bumiller says that in the past two thousand years women’s status plummeted. As wandering tribal clans began to settle, women became less involved in the means of production, and gender roles became more demarcated, with men (who brought home the bacon, or perhaps wild boar) taking a superior position. Bumiller also references historian Romila Thapar’s theory that in India the oppression of women was part and parcel of preserving caste distinctions. (Apparently, some nasty fellow named Manu codified the caste system around

A.D.

200 and also said this of us ladies: “Woman is as foul as falsehood itself.” Whoa. What did his mother do to him?!) Caste meant controlling who married whom so that the gene pool did not get polluted (read: putting guys like Manu in danger of losing their power). Further, Bumiller quotes Thapar as explaining, “To avoid pollution, you must control birth . . . you lose control over birth if you lose control over women.”

Et voilà,

the institutionalization of oppression.

All this from a culture that worships millions of goddesses. This worshipping of women in religious practice and trashing them in real life is one of my favorite global-religious ironies, certainly not limited to the Hindu cultures.

Hypocrisy. Misogyny. Suffering. Organized religion.

Who needs it?

I think ungenerously, short-tempered with dehydration. I pop a Pepto-Bismol tablet, just to try something new. I wish I could ask Kiran Bedi about this. With her mastery of the spiritual, and direct vernacular, she could surely help me understand where orthodoxies fall apart, or at least where those in her own culture go astray.

Julie hails a horse-drawn flatbed wagon that will serve as a makeshift dolly, thus giving our low-rent documentary high-rent effects. Jaipur is the first place we’ve been that looks like the images of regal India of times past. We trundle past small palaces and Rajasthani men in bright red turbans and handlebar mustaches as we soak up the “Pink City” (a bit of a misnomer as the buildings are more of a hazy orange).