After the People Lights Have Gone Off (13 page)

Read After the People Lights Have Gone Off Online

Authors: Stephen Graham Jones

Tags: #Fiction, #Ghost, #Short Stories (Single Author), #Horror

“Maybe I was camping,” Dick says.

“Camping,” Sammy says, tossing the lighter across.

It traces a perfect arc through the storeroom.

Dick’s hand rises to meet it.

The sleeve anyway.

Eye contact with Sammy the whole slow time.

•

The four-hour shift grinds by. Two bagboys aren’t needed, but Sammy’s there anyway, whistling to himself when the customers aren’t around. Some sick melody not heard by humans for fifty years or more, until now.

“What’s her name, that one at the carwash?” Sammy asks once.

Dick flips him off. In his head.

Instead of bagging, he’s sweeping. Has to take the padded mats of all six registers out back, blow them out with the hose then hang them over the safety rail to dry.

Two cigarettes later, he’s slouched back in, the rain beaded on the black shoulders of his hoodie, a thousand tiny droplets, the world captured in each of them.

There’s trash to be hauled out, spills to be mopped, soup to be counted and (re)tagged.

An hour shy of ten—clock-out—Dick plays the mom-card: she’s making a cake, it’s her birthday, Glory has to go to bed early.

The assistant manager spins once on his metal stool, considering, and it’s finally a financial decision, Dick knows: that’s one less hour of minimum wage to pay out at the end of the week.

“She never knew, either,” Dick says, shrugging the hood up over his head.

“Cat?” the assistant manager asks.

Catressa, yes.

Dick says it with his eyes, mostly.

The assistant manager spins halfway back around, is already studying something on his desk.

“She’ll make a good waitress somewhere,” he says as goodbye, then his whole massive frame chuckles.

On the way out, Dick runs his hand along the label-edge of the condiments shelf, shifting all the prices one item over. Sometimes two.

His other hand balled tight in his sleeve, where no one can see.

•

One hour and nine minutes later—the car not late yet, Mom—Dick’s got the headlights off, is idling at the fire curb by the cart corral, where the squeaky wheeled go to die their slow public deaths.

The air’s grey, is at least half exhaled smoke.

Waitress my ass, Dick’s saying to himself every few drags.

The last cigarette he lit was fifty minutes ago. He’s not asking where the new ones are coming from anymore, or how they’re getting lit.

Off hatred, he knows.

Sixteen years of it already.

Dick smiles. Starts to rub a port hole in the windshield to see from but realizes at the last moment that that would mean looking at his right hand. So he uses his left, and, instead of a rubbed-clean hole—the defroster sucks—he writes his name backwards, so it’ll be readable from the front: D R A H C I R.

No idea why he never thought of that till just this moment.

Or, like he’s been saving it for now, yeah.

Like clockwork, then, Sammy ambles out into the night, leaning back to stretch his back, both his hands on his hips.

When he comes down from that stretch, he sees it, what Dick’s left: the turquoise and silver lighter.

Just standing there erect on the shiny blacktop.

Sammy cocks his head, takes a careful step forward, then another step, and Dick lowers his—not his hand, but the sleeve, he watches as the long sleeve of the hoodie swallows that five-speed little shifter, deep throating it.

And—more clockwork—the front tires chirp their warning just as Sammy’s leaning down for this impossible thing, this lighter, and, because he’s old, instead of standing all the way to take the Corolla’s impact, he only turns his face to the bright, bright headlights, his shadow thrown so far behind him. Almost as far as he’s about to fly.

Dick smiles, but it’s so deep in the darkness of his hood that Sammy never sees it.

But of course one day our father needed something flat and disposable to mix some JB Weld putty on, so he cut down into it with his pocket knife, just hacking a rough square from the side, and I admit that, one bored afternoon, I probably decorated one of the cut-out handles with the kitchen scissors. Nothing regular or patterned, just uneven little triangles snipped here and there. I was imagining if the cardboard were steel, then those points I was leaving would be sharp, would de-finger whoever reached down for a grip, would make the side of the box into a shark mouth.

Any day it was taking its fatal trip to the curb, I mean, and it would have that week if Mom hadn’t ditched a load of socks in it then not got around to folding them until after trash day. But the world, it always keeps turning, doesn’t it? She got around to the socks, and of course at some point in there we tried to trap the cat under the box (fail), tried to capture a bird in the backyard (partial success), then finally, perhaps overestimating its reliability, we tried using it as a stool (crunch). So we stapled it back together as well as we could, with the staple gun we’d been trying to reach in the first place.

That was what did it, too, we think.

We didn’t get the inner flaps lined up with the sides of the box like they had been, so the box’s dimensions were off a hair, and it wasn’t quite square anymore.

Big deal, right?

It was just a box, and we got the stapler back up in its cabinet, and nobody knew anything.

The next morning, though, our dad’s cereal bowl woke us, by breaking on the kitchen floor.

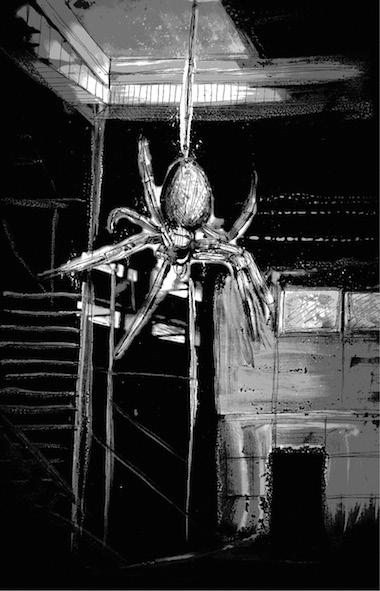

By the time we got there, we understood why he’d let his cereal go like that: the inside of the box was crawling with spiders. It was writhing with them, hissing with them, boiling with them.

My mom caught our father’s eye and our father just shrugged.

I smiled.

With a shovel, we guided the box across the floor, out the nervous bump the sliding door was, and tipped it off the back porch. The spiders didn’t explode away from the box, but they didn’t cling, either. They just ambled off on their own time, back to their dark places.

“The wax,” my mom decided. It had aged to some state of tastiness the spiders couldn’t resist.

Maybe.

The next morning, it was just a box. Our father stood at the sliding door and ate his cereal and watched it lay there on its side, harmless at the edge of the porch, the sun breaking over the back fence.

Later that day, Mom not watching, we crawled out to the box on fingertips and toes, smelled it. It was just cardboard, a bit damp, its top side sagging in a touch now. We caught spiders, dropped them in, but the spiders didn’t care, just hooked a leg up on the side, then another, and crawled up, out.

The next morning, the box was full of tarantulas. Ones that weren’t even supposed to come up from their holes for months, if this year at all.

“Burn it,” my mom said.

“It’s not the wax,” our father said.

He took the day off from work, applied the made-up science in his head to the box. Polaroids, rulers, protractors, compasses, spiral notebooks, yarn, coins for size, different kinds of light, different kinds of metal. Magnets, smoke, water vapor. Tuna, but the cat just jumped in, ate it, growling at us the whole time.

That night he pulled a chair up to the sliding glass door and made a pot of coffee and watched the box, out on the porch.

The spiders came to it like a spill of oil seeping across the lawn. Like a shadow, spreading, and, according to our father, he never saw them come up over the edge, even, to get inside. But they must have. There they were.

My dad called in sick again, his fingers jittery.

Backing out of the drive for either the hardware store or the library, he backed over our third new dog for that year. It was a solemn lunch. Promises were made, tears were snuffed back up into sinus cavities.

We buried Blackie Dos in the alley, me and my brother standing guard at either end for the trash truck, who might report us.

Before we could come back through the gate, Mom handed the box over the fence.

Our father knew when he was beat.

He went in to his shift the next morning, never saw what we were pretty sure we did: Blackie Dos—or Blackie Dos’s exact twin, just more raggedy—limping down along the fence line behind all the houses. Going to live on some other street.

The box he’d crawled out of was tumped over by the trash.

After our father had dropped it in reverently, moving his shoulders and arms either exactly like a good husband or in exact imitation of a good husband, we’d got it back out, set it carefully by the dumpster, because it had to be sitting up like that to work, we were pretty sure.

But it could have been the wind that tumped it over. Or cats. And there were Blackie Doses everywhere that summer.

Still.

That weekend, his second six-pack giving him ideas, our father took apart our old toy box and raided the woodpile, re-built the box but larger this time, and sturdier. But he kept to the exact dimensions, was consulting his spiral notebooks before each pull of the saw.

He told us that what had happened was that we’d stumbled on some secret of the universe, some private geometry, some magic dimension that allowed things to happen that usually couldn’t, but that probably always wanted to. And spiders were tuned to that, or had enough eyes to see it right. Something.

I reminded him about the decorated handle. The razor blade handle, the shark mouth handle. He studied the Polaroid, compared it to another Polaroid, got the file and adze out again, but only after tracing his cuts with a pencil, and coloring them in to be sure they were going to match.

By morning, it was real.

“If a little one got spiders?” he said, and balanced it into the bed of his truck. It was the same box, just scaled up from peaches to…to watermelons. Or whatever fruit’s one bump up from that.

We took it to the edge of town, out by the dump, and set it down by a fence, pitched our tent a few truck lengths away.

We fell asleep first, like always, in spite of our best efforts and our promises to keep pinching each other awake.

The next morning there was a scuffling coming from the box. We edged in behind our father, behind the lever-action he’d smuggled out of the house.

The scuffling was hooves.

There was a baby horse in the box.

Its legs were broken, though.

We followed its drag marks back to an old refrigerator somebody had off-loaded against the fence that kept the dump in.

“Why would—?” our father said.

“What?” I said up to him.

“Do this.”

Itself, I thought, but didn’t say.

I felt like crying.

By the time we got back to the box, it was on its side. The baby horse was trying to stand. And then it was.

“Warm the truck,” our father told us, tossing the keys over, and we heard the rifle fire once behind us. Heard the splat it made. It made us walk faster, with our hands made into fists, to keep the pictures in our heads from happening.

We balled the tent up and pitched it into the back of the truck, its poles and stakes sticking out like bones, dragging like fingers. On the way past the box, our father reconsidered, veered a little over, ran over it enough for it to crunch, explode beneath our feet.