Alex's Wake (16 page)

Authors: Martin Goldsmith

Such words were sweet music to the ears of Joseph Goebbels. The propaganda minister was eager to show the world that it was not just Germany that had no use for the Jews. He and his colleagues in the German Foreign Office hastily issued a statement. “In all parts of the world,” it read, “the influx of Jews arouses the resistance of the native population and thus provides the best propaganda for Germany's Jewish policy. In North America, South America, France, Holland, Scandinavia, and Greeceâwherever the Jewish migratory current flowsâa marked

growth of anti-Semitism is already noticeable. It must be the task of German foreign policy to encourage this anti-Semitic wave.”

As the

St. Louis

steamed steadily onward, mounting internal and external pressures on the Cuban government threatened to prevent the ship from disembarking her passengers in a timely fashion. Such organizations as the London-based International Committee on Political Refugees, the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee of New York, and the Jewish Relief Committee in Havanaâall of which were following the progress of the journeyâslowly came to the realization that trouble lay dead ahead.

The passengers on board the

St. Louis

, however, knew nothing of those matters and felt only giddy pleasure as they sailed ever closer to the warm waters of the Caribbean. Within a day or two of their departure from Hamburg, most of the adult refugees had cast off their sadness and began taking full advantage of the splendid amenities their vessel offered. A typical day began with a full breakfast that included everything from eggs and fruit to kippers and cheese. The older passengers would then enjoy a few hours reclining in deck chairs under the sun as they sipped from mugs of excellently brewed coffee. After retreating to the dining hall for lunch, they might engage in a game of shuffleboard or deck tennis or swim a few laps in the ship's pool and attend an afternoon tea dance. Younger passengers enjoyed playing a horse-race game in which wooden horses advanced around a track in accordance with the throw of ivory dice. At night, following another sumptuous meal, there were dances, movies, and lectures to enjoy. The amusements must have seemed equal parts marvelous and amazing to those refugees, many of whom had recently spent time in concentration camps and all of whom had spent years as second-class citizens in their own land.

Twelve-year-old Herbert Karliner played the horses, swam in the pool, and also indulged his fascination with long-distance communication by hanging around the telegraph operator, watching him send messages. The operator was very friendly and didn't object to Herbert's presence, but one day the young man came face to face with Captain Schroeder, who told him kindly but firmly that he was not allowed in the telegraph room and would have to leave immediately.

Herbert Karliner, aged 12, poses with his father, Joseph, on the top deck of the

St. Louis.

(Courtesy of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum)

I have no firsthand report on how Alex and Helmut spent their days and nights on board the

St. Louis

. But I imagine that Alex, only five months removed from his ordeal in Sachsenhausen, took full advantage of the opportunity to eat his fill three times a day and simply relax in a deck chair or in his berth. And I can see my uncle, just seventeen years old, checking out a book from the ship's library and reading lazily in the sun, or shyly making the acquaintance of some of the other young people aboard. Perhaps he exchanged a word and a smile or two with Ilse Karliner, Herbert's older sister, who was fifteen.

Ten days out from Hamburg, however, even as the

St. Louis

passengers were growing accustomed to their nice new routines, death intruded into their floating Arcadia. Moritz Weiler had been a professor at the University of Cologne for many years before the Nazis forced him to

resign in 1936. The shock of losing his position as a respected academic had taken a toll on his health, and the effort required to flee the country of his birth had weakened him further. As his shipmates enjoyed the many charms of the voyage, Professor Weiler remained bedridden in cabin B-108, visited frequently by the ship's physician, Dr. Walter Glauner. Despite the doctor's best efforts, Weiler died on the morning of Tuesday, May 23. His widow, Recha Weiler, declared her wish that her husband be buried in Cuba, but Captain Schroeder, already gleaning that there might be complications upon their arrival, convinced her of the necessity of a burial at sea.

Shortly after 10:00 that night, after a brief funeral on A Deck attended by Captain Schroeder, First Officer Ostermeyer, and a few refugees, Professor Weiler's body was wrapped in his prayer shawl and then placed into a sailcloth shroud covered by the blue and white HAPAG flag. Then his body slid into the ocean. Remembering Weiler's passing several months later, the captain wrote, “It broke his heart to feel that in his old age he had to leave the land where, all his life long, he had worked on the best of terms with his colleagues. Seeing him in his reduced state, I felt that his will to live had gone.” After the funeral, Captain Schroeder presented Recha Weiler with what would become for her a treasured memento: a map marked with the lonely spot in the Atlantic where her husband had been buried. There were now 936 passengers on board the

St. Louis

, most of whom had no idea that their number had been reduced by one.

Two nights later, on Thursday, May 25, the passengers enjoyed a costume ball in the ship's nightclub, a party that traditionally signaled the impending end of a voyage. The band played a series of Glenn Miller tunes and, with everyone assuming that their “shipboard money” would soon be worthless, a great deal of liquor was purchased and consumed, contributing to a most convivial atmosphere. The party finally broke up at three o'clock in the morning. Within twenty-five hours, on Saturday, May 27, the

St. Louis

pulled into Havana Harbor, her horn blasting most of the passengers awake at 4 a.m. The breakfast gong sounded at 4:30, and despite the early hour, the dining rooms were soon full of sleepy, eager people, excited that their two weeks at sea were nearly at an end.

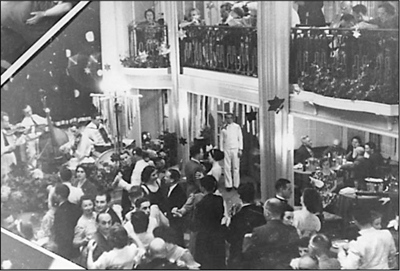

Passengers on board the

St. Louis

, some of whom had spent weeks in concentration camps six months earlier, enjoy a dance in the ship's ornate ballroom. Note the Star of David affixed to the central column

.

(Courtesy of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum)

But as day broke, the passengers gradually became aware that something was wrong. The ship was still out in the harbor and hadn't tied up at the dock. Late on Friday afternoon, Captain Schroeder had received a cable from Luis Clasing, HAPAG's Havana director, instructing him to “not, repeat not, make any attempt to come alongside.” Cuban President Bru was standing firm behind Decree 937 and had let the Hamburg authorities know about it in the most unambiguous manner possible. On Friday night, however, Robert Hoffman, who had his own reasons for wanting the

St. Louis

to disembark its passengers, had met with Manuel Benitez Gonzalez, the immigration director, who uttered soothing words of reassurance. “My friend, Bru has to keep up a pretense. Tonight he lets the ship into Cuban waters. Tomorrow he allows it into the harbor. The next day it will be at the pier. Then off they will come, and our worries are over. I am a Cuban. I understand the Cuban mind.”

Early on Saturday morning, matters seemed to be moving forward as a white-suited Cuban doctor representing the Havana Port Authority drew up alongside the

St. Louis

and came aboard, to be greeted by Dr. Glauner and escorted to the bridge. There Captain Schroeder presented the Cuban doctor with the ship's manifest, which listed every passenger, and signed a statement in which he swore that none of them was “an idiot, or insane, or suffering from a contagious disease, or convicted of a felony or another crime involving moral turpitude.” The Cuban doctor was unsatisfied, however, and insisted on a personal inspection. Every passenger was called to the social hall and filed slowly past the doctor, who made no comments but informed Dr. Glauner of his approval. When he left the ship and his launch sped back to land, everyone on board assumed that, the medical formality having been dispensed with, the

St. Louis

would now make her way to a pier. But she remained at anchor.

Over the next few days confusion reigned, as meetings and negotiations involving President Bru, Manuel Benitez Gonzalez, Captain Schroeder, Luis Clasing, and Milton Goldsmith of Havana's Jewish Relief Committee all failed to arrive at a satisfactory resolution. It was President Bru's unyielding position that the Benitez landing certificates were invalid and thus the vast majority of the

St. Louis

refugees would be entering Cuba illegally should they be allowed to disembark in Havana. Twenty-eight lucky passengersâtwenty-two Jews who were able to pay the additional $500 to obtain approved visas, plus four Spaniards and two Cubansâwere allowed off the ship. But President Bru stood firm where the rest of the 908 refugees were concerned.

At one point in the discussions, Cuban Secretary of State Juan Remos met with President Bru to argue the moral implications of denying asylum to these victims of Nazism and to remind the president that his stance might cost him the disfavor of the United States. Unbeknownst to the secretary, the plight of the

St. Louis

refugees had indeed become a topic for discussion in official American circles, but so far the direction of those discussions did not, in fact, contradict the Cuban president's position. Assistant U.S. Secretary of State George Messersmith wrote in a memorandum that it was his understanding

that the United States would not “intervene in a matter of this kind which was purely outside of our sphere and entirely an internal matter of Cuba.”

The abiding strategy of the United States in regard to Latin America for the previous six years had been known as the Good Neighbor Policy (GNP). Formally announced during his inaugural address by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933 and reaffirmed by Secretary of State Cordell Hull later that year, the Good Neighbor Policy held that “no country has the right to intervene in the internal or external affairs of another.” Since then, the GNP had led to the withdrawal of U.S. marines from Haiti and Nicaragua in 1934 and, in that same year, ended the lease agreement with Cuba permitting American naval stations on the island, with the exception of the base at Guantanamo Bay. By 1939, the GNP was viewed in Washington as a major foreign policy success story, winning wide support among Latin and South American nations, and a position not to be tampered with lightly. The saga of the

St. Louis

, therefore, would have to be settled by Cuban officials themselves without either overt or covert actions by the United States.

During that weekend, as the ship that was to have ushered them to freedom in the New World lay at anchor and in limbo in Havana Harbor, the 908 refugees passed the time as best they could in the hundred-degree heat and heavy humidity. They took snapshots of the city skyline and purchased bananas, coconuts, pineapples, and other tropical fruits from the enterprising vendors who drew up their little boats alongside the luxury liner. Some relatives of the refugees, who had come to the dock to welcome their families ashore, circled the

St. Louis

in private craft, shouting messages of patience and encouragement. A man paddled his canoe close enough to a second-class porthole to wave to his child, who was being held aloft by his wife. During the long hot nights, the crew of the

St. Louis

trained her searchlights onto the dark oily waters of the harbor to make sure that no one would take matters into his or her own hands and attempt to swim to shore.

On Monday, May 29, Robert Hoffman, the HAPAG assistant manager and

Abwehr

spy, was becoming increasingly nervous that his mission might be compromised by the inability of his courier to reach dry land. He arranged for a few hours' shore leave for several

St. Louis

crew members, including Otto Schiendick. Shortly after 6 p.m., a launch containing the crewmen made its way from ship to shore, where Schiendick separated himself from the others and walked rapidly to the HAPAG office. There Hoffman handed him a carved walking stick that had been hollowed out and now contained the information eagerly awaited by the military intelligence forces back in Germany. Schiendick then strolled along the Malecón, the grand esplanade that borders the harbor, making full use of his new stick, until his shore leave was over. As the launch brought him and his fellows back to the safety of the

St. Louis

, Hoffman observed him through binoculars. Once Schiendick and his walking stick were back on board, Hoffman cabled his superiors in Berlin that the operation had gone smoothly. From his point of view, what happened to the refugees was now irrelevant; so long as the

St. Louis

returned to Hamburg, as it surely would, his mission would be a complete success.