Alex's Wake (13 page)

Authors: Martin Goldsmith

Our next train leaves promptlyânaturallyâat 10:50 and pulls into the immense Hamburg

Hauptbahnhof

two minutes early. The Central Station, as it's known in English, opened for business on St. Nicholas Day, 1906, and claims to be the busiest railway station in Germany and, after Paris, the second busiest in all Europe. Today, the hordes of Hamburgers thronging the station are made more imposing by the umbrellas they wield as they stride rapidly through the vast interior, which includes twenty separate tracks and an overhead emporium with restaurants, flower shops, bakeries, and a fully stocked pharmacy.

We find our way to the U-Bahn, or subway, and navigate the underground system for a distance of six stops, emerging at St. Pauli Landungsbrücken, just steps from the River Elbe. The foul weather surprises us anew with its undeniable rudeness. Leaning into a stiff wind, our eyes assaulted by sheets of horizontal rain, we trudge slowly down one of several movable bridges leading to the long landing pier that for more than a century and a half has been an embarkation point for transatlantic voyages. The tide is high, gulls wheel and shriek overhead, and the clouds and mist conspire together to reduce visibility to mere yards. Through the gloom, however, it is possible to see a neon sign on

the opposite bank of the Elbe advertising a long-running production of the musical

The Lion King

.

The long pier, more than the length of seven football fields, was heavily bombed during the Second World War and rebuilt during the 1950s and '60s. Despite today's wind and weather, restaurants along the pier are serving English-style fish and chips and traditional German brews. Several hundred yards to the west, a sizable Greek tanker is tied up, and immediately in front of us, a small catamaran is readying for a tour to the island of Helgoland in the North Sea. It is, apparently, just a normal Tuesday on the Hamburg docks.

On such a day as this, I repeat to myself over and over, on a May evening seventy-two years ago, my grandfather and uncle set off on a voyage from this very spotâa voyage that was supposed to end in freedom for them and eventually for the whole Goldschmidt clan. I lean on a railing and squint through the wind and rain, trying to peer past the decades and conjure up a vision of their unfortunate vessel. There is water on my cheeks, the fresh mixing with the salt in the manner of the River Elbe giving way seventy miles downstream to the inexorable pull of the sea.

B

EGINNING IN

1847, a new fleet of ships began weighing anchor from the port of Hamburg and sailing to destinations all over the globe. Most of the journeys ended in the New World, in Rio de Janeiro, Buenos Aires, Guayaquil, and Havana; in New Orleans, Baltimore, Boston, Montreal, Halifax, and New York City. These were the ships of the mighty

Hamburg Amerikanische Packetfahrt Actien Gesellschaft

âliterally, the Hamburg American Packet-Shipping Joint Stock Companyâor HAPAG for short, also known simply as the Hamburg-America Line. In the company's early years, HAPAG ships made the crossing from Hamburg to New York via Southampton in forty days. By the beginning of the twentieth century, the journey had been reduced to less than a week.

Many celebrated ships flew the blue and white HAPAG flag. In September 1858, the

SS Austria

caught fire in the middle of the

North Atlantic and sank, killing 463 of its 538 passengers. Among the survivors was Theodore Eisfeld, the music director of the New York Philharmonic, who had managed to lash himself to a plank and drifted on rough seas for two days and nights without food or water before being rescued. In 1900, the 16,500-ton

SS Deutschland

made history by sailing from Hamburg to New York in just over five days, maintaining a speed of twenty-two knots. Twelve years later, HAPAG's

Amerika

was the first ship to send radio signals warning the luxury liner

Titanic

of icebergs in the vicinity.

But in the storied chronicles of the Hamburg-America Line, which merged in 1970 with Bremen's North German Lloyd to form today's Hapag-Lloyd Corporation, no ship rivals the infamy of the

SS St. Louis

. She was built by the Bremer-Vulkan Shipyards in Bremen, at the time the largest civilian shipbuilding company in the German Empire, and launched on May 6, 1928. Her maiden voyage, with stops in Boulognesur-Mer, France, and Southampton, England, en route to New York City, began on March 29, 1929. The

St. Louis

was among the largest ships in the entire HAPAG line, weighing 16,732 tons and measuring 575 feet in length. Diesel powered, gliding through the water on the strength of twin triple-bladed propellers, she regularly reached speeds of sixteen knots as she sailed the trans-Atlantic route from Hamburg to Halifax, Nova Scotia, and New York, and on occasional cruises to the Caribbean. Her cabins and tourist berths were designed to accommodate 973 passengers. She was, in every measure of the phrase, a luxury liner; her gleaming brochures proclaimed, “The

St. Louis

is a ship on which one travels securely and lives in comfort. There is everything one can wish for that makes life on board a pleasure.”

By the spring of 1939, the

St. Louis

had been serving its largely well-heeled clientele for ten years. The single voyage for which she remains most famous was about to commence, brought about by the confluence of several interlocking events.

On January 24, 1939, Nazi Field Marshal Hermann Göring appointed Reinhard Heydrich to direct the Central Office for Jewish Emigration. The Final Solution to what the Third Reich termed the Jewish Problem still lay several years in the future; for now the goal was

simply to get as many Jews out of Germany as possible. Heydrich knew Claus-Gottfried Holthusen, the director of the Hamburg-America Line, and knew also that, since 1934, the Reich had become the majority shareholder in HAPAG, thus compromising the independence that the shipping company had enjoyed for the past ninety years. And Heydrich was aware that HAPAG had recently been troubled by financial setbacks exacerbated by the uncertain international situation. On its last voyage from New York, for instance, the

St. Louis

had sailed with only about a third of her berths occupied.

Heydrich immediately recognized an opportunity that would be mutually beneficial for the Reich and for HAPAG. He informed Göring and Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels about the facts as he saw them, and by the middle of April, they had arranged that the

St. Louis

would sail from Hamburg to Havana, Cuba, on May 13, bearing nearly a thousand Jewish refugees. Everyone involved was satisfied. Göring relished the opportunity to demonstrate to Chancellor Hitler that he was ridding the Reich of Jews. Goebbels perceived the nearly perfect propaganda possibilities: Germans would be pleased that more Jews were leaving the country, while the international community, still shocked from the reports of

Kristallnacht

violence, would observe that Germany was graciously allowing its Jews to leave unharmed and unimpededâand on a luxury liner, no less. The Hamburg-America Line would turn a profit on a voyage at a time when it sorely needed one. (While the

St. Louis

passengers would be refugees, to be sure, they would be charged the standard fares of 800 Reichsmarks for first class and 600 Reichsmarks for tourist class.) And last, and certainly least, the Jews themselves would surely appreciate this highly civilized manner of being booted out of their own country.

The unmistakable message of the November Pogrom had sunk in for a majority of Germany's Jews, and they began a determined scramble to flee. In 1938, the number of Jewish émigrés from Germany numbered about thirty-five thousand. During the following year, that figure nearly doubled, to sixty-eight thousand. In the days and weeks following

Kristallnacht

, lines were long outside foreign embassies and consulates in all major German cities, as Jews waited to obtain the necessary papers

to apply for visas. While every German Jew felt the pressure to leave, some were under more immediate duress than others.

After nearly a month of unspeakably harsh treatment in Sachsenhausen, Alex Goldschmidt was released on December 7, 1938, and informed in no uncertain terms that he had six months to leave the country of his birth or face a second arrest. So my grandfather shakily returned home to Oldenburg and, after spending a week or so recovering from his ordeal and talking matters over with his family, he took the train to Bremen and visited the Cuban consulate. There he applied for permission to emigrate to Cuba in the spring, filling out an application for himself and one for his son Helmut. They planned to establish residency in the New World and to send for the rest of the family a few months later. It must have seemed an eminently logical and sound strategy.

Cuba was among the few places on earth that even considered taking in Jewish refugees during the months following the November Pogrom. In July 1938, delegates from Cuba and thirty other countries gathered in France for the Evian Conference, to discuss what to do about the increasing number of Jews who wanted out of Nazi Germany. Once both the United States and the United Kingdom made it clear that they had no intention of increasing their quota of immigrants from Germany and Austria, the Evian Conference adjourned with most of the countries following the lead of its major players. The conference was ultimately considered a tragic failure, with Chaim Weizman, the future first president of Israel, declaring that “the world now seemed to be divided into two parts: those places where the Jews could not live and those where they could not enter.” Cuba, at least, presented itself as a theoretical haven, and Alex, his determination still intact despite his weeks in Sachsenhausen, saw the island nation as a practical solution to his family's latest challenge.

Over the next several months, the Goldschmidt family did all it could to conserve its resources, as Alex knew that many fees, both legal and extralegal, would accompany the emigration process. Now that his business had been officially liquidated, he had no steady source of income. So on December 28, Alex moved his family from the apartment

on Ofenerstrasse to a smaller, less expensive apartment on Nordstrasse, just a few blocks from the railroad station.

Alex, Toni, Eva, and Helmut spent the next few months nervously waiting for news from the Cuban consulate in Bremen. Finally, in early March 1939, the family learned that Cuba had granted visas for Alex and Helmut. But the next day, a letter arrived from Manuel Benitez Gonzalez, the director-general of Cuba's Office of Immigration, informing them that Alex and Helmut would each have to purchase a special landing certificate if they intended to disembark in Havana. The price for each certificate was 450 Reichsmarks, a small fortune given the ever more Spartan circumstances of the Goldschmidt family.

Alex realized that they would have to tighten their belts yet again before the journey west. So on March 21, they moved to an even smaller apartment at 17 Staulinie. They were now only a block from the train station, close enough that the constant chug and chuff of engines caused their walls to shiver.A month later, the so-called Benitez certificates arrived. Alex placed the precious documents along with the visas into a cardboard folder, which he stored under his mattress. He checked their safety every night and every morning and several times during the day; other than his wedding ring, he owned nothing of greater value than those four pieces of paper.

The time had now come to secure passage to Cuba. He purchased two tourist class tickets for the May 13 voyage of the

St. Louis

, at a price of 600 Reichmarks (about $240) each. Alex was also obliged to pay an additional 460 Reichsmarks (about $185) for what the Hamburg-America Line termed a “customary contingency fee.” This additional expense covered a return voyage to Germany should what HAPAG called “circumstances beyond our control” arise. The line insisted that this “contingency fee” was fully refundable, should the journey proceed as planned.

Alex returned to Oldenburg in triumph, bearing his precious purchases. They had been extremely expensive, but now he had everything he neededâvisas, landing certificates, ticketsâto apply for a passport. On Monday, May 1, he and Helmut visited the Oldenburg offices of the Emigration Advisory Board to fill out individual applications for the “issuance of a single-family passport for domestic and foreign use.”

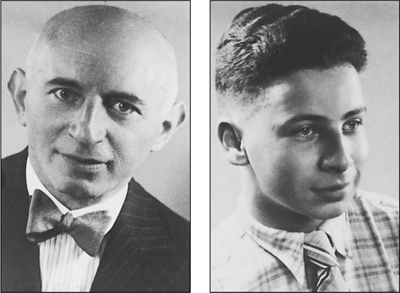

The photos taken of Alex and Helmut that they used for the passports that enabled them to board the

St. Louis

. These were also the photos that, attached to the space above our rear-view mirror, accompanied us on our journey

.

Father and son completed their forms in much the same manner. On the line marked “profession,” Alex wrote “salesman” and Helmut “student.” Thanks to this application, I know that my grandfather's eyes were gray and my uncle's were blue. On the line marked destination, they both wrote “Cuba.” Both practiced the same small deception: under their address, which they listed as 17 Staulinie, there was a line requesting any previous addresses within the last year. Although the family had in fact moved twice in the past twelve months, they declared that they had lived on Staulinie “for years.” Perhaps Alex thought that a history of frequent moves might indicate a troublesome lack of stability. Whatever the reason, their white lie seems to have passed unnoticed.