All the King's Cooks (11 page)

Read All the King's Cooks Online

Authors: Peter Brears

11.

A Marchpane Mould

This early sixteenth century marchpane mould bears the IHC monogram of Jesus, a popular motif in the decorative arts of this period, and the inscription, cut in reverse, ‘An harte that is wyse will obstine from sinnes and increas in the workes of God’.

12.

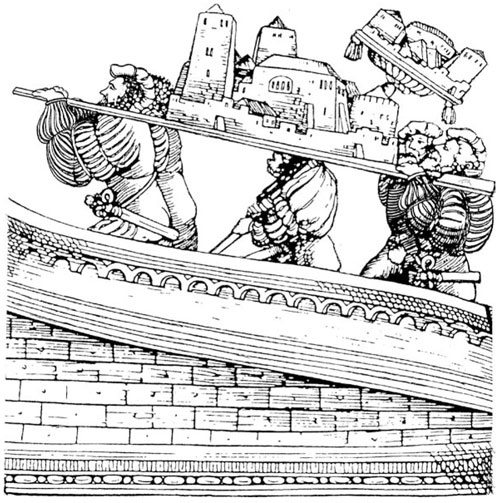

Subtleties

The main decorative feature of any Tudor feast was a’subtlety’, which could be a model of a building, a saint, a worthy or a virtue, with appropriate mottoes. Here in Hans Springlee’s print,

The Battle before the Rouanne

, from

The Triumph of Maximilian

(1526), two subtleties are being carried up to the Emperor. The print provides us with rare evidence of their scale and appearance, and the manner in which they were presented.

The finest account of Tudor confectionery comes from George Cavendish’s biography of Cardinal Wolsey, in which he describes the preparation and service of a magnificent feast for the reception of the French ambassadors at Hampton Court in October 1527.

25

It is well worth quoting at length. First, Wolsey called for his principal officers of his house, as his steward, Comptroller, and the Clerkes of his kitchen – whome he commaundyd to prepare for them a bankett at Hampton Court, and noither to spare for expences or travell to make them suche tryumphant chere as

they may not only wonder at hit here, but also make a gloryous report in their contrie, to the Kynges honour & that of the Realme … [Also, they sent for] all the expertest Cookes besydes my lordes that they could gett in all Englond where they myght be gotten to serve to garnysshe this feast. The purveyors brought and sent In suche plenty of Costly provysion as ye wold wonder at the same. The Cookes wrought bothe nyght & day in dyvers subtiltes and many crafty devisis where lakked nother gold, Sylver ne other costly thyng meate for ther purpose …

Nowe was all things in a redynes and Supper tyme at hand. My lordes Officers caused the Truppettes to blowe to warne to Supper And the seyd Officers went right discretly in dewe order And conducted thes nobyll personages frome ther Chambers unto the Chamber of presence where they shold Suppe And they beyng there caused them to sytt down ther servyce was brought uppe in suche order &c Aboundaunce both Costly & full of subtilties wt suche a pleasaunt noyce of dyvvers Instruments of musyke tht the French men (as it semyd) ware rapte in to an hevenly paradice … devysyng and wonderyng uppon the subtilties … Anon came uppe the Second Course wt. so many disshes, subtilties, & curious devysis wche. ware above an [hundred] in nomber of so goodly proporcion and Costly that I suppose the Frenchemen never sawe the lyke, the wonder was no lesse than it was worthy in deade. there were Castelles wt. Images in the same, powlles [St Paul’s] Chirche & steple in proporcion for the quantitie as well counterfeited as the paynter shold have paynted it uppon a clothe or wall. There were beastes, byrdes, fowles of dvers kyndes And personages most lyvely made & counterfet in dysshes, some fighting (as it ware) wt. swordes, some wt. Gonnes and Crosebowes, Some vaughtyng & leapyng, Some dauncyng wt. ladyes, Some in complett harnes lustyng [fighting] wt. speres, And wt. many more devysis than I am able wt. my wytt to discribbe. Among all oon I noted there was a Chesse bord subtilly made of spiced plate wt. men to the same, And for the good proporcyon bycause that frenche men be very experte at that play my lord gave the same to a gentilman of fraunce commaundyng that a Case shold be made for the same in all hast to preserve it from perysshyng in the conveyaunce therof to hys Contrie.

13.

The Waddesdon Court Figures

The sugar figures made in the Confectionary probably bore a close resemblance to these early sixteenth century oak figures which originally stood around the frieze of the dining room at Waddesdon Court, Stoke Gabriel, in Devon. This selection shows (top) the Christian Worthies – King Arthur, Charlemagne and Godfrey de Bouillon – and (bottom) the Pagan Worthies – Hector of Troy, Julius Caesar and Alexander the Great, as described in the introduction to Caxton’s

Morte de ‘Arthur

of 1485. They may now be seen in the Torquay Museum.

To make many of the figures a new kind of sugar plate was introduced, one that dried to a pure matt-white finish ideal for receiving decoration. The first recipe for this sugar plate to be published in England was in Girolamo Ruscelli’s

The Secretes of the Reverend Maister Alexis of Piedmont

of 1562, but by this time it had probably been in use in the royal confectionary for many years. Instead of having to be boiled, the sugar was simply ground to a fine powder and then sifted to produce the equivalent of today’s icing sugar. Once mixed with a natural vegetable substance, gum tragacanth, as a binder, and lemon juice and rosewater for flavour, it was transformed into one of the most versatile of all confectionery media.

The moulds used for this paste were used bone-dry – just dusted with a little finely powdered sugar, starch or spice to prevent the sugar plate from sticking inside them. To make a round fruit such as an orange, for example, pieces of the soft, pastry-like mixture could be pressed into each section of a plaster, or a pottery mould,

the edges trimmed level with a knife and brushed with a little gum tragacanth solution to make the parts stick together; then the mould would be reassembled and after a while the completely spherical fruit turned out into a box of freshly sifted flour, which would hold it in shape until it had hardened. The sugar plate could also be cast in shallow wooden moulds, perhaps only an eighth of an inch (3–4mm) in depth; the surplus would be cut off with a knife, and then the sugar plate would be turned out by holding the mould upside down above a worktop, at a slight angle from the horizontal, then sharply banging down the lower end to make the sugar plate drop out face upwards. The moulding could then be carefully draped over a ‘former’, where it would set into the shape of part of a limb, a torse, a shield – or whatever was being made. Once perfectly dry, the edges of each piece would be neatly trimmed and stuck to other pieces using a strong gum-tragacanth and icing-sugar ‘cement’, in much the same way as you might assemble the parts of a injection-moulded plastic construction kit.

14.

St Catherine

This figure, shown holding her symbolic wheel in her left hand, was made by pouring boiling sugar into the accompanying mould, which beforehand had been either soaked in water or brushed with oil to enable the complete cast to be easily removed. The mould, now in the Museum of London, was found in the Old Bailey.

The completed figure could now be decorated – its smooth, white and slightly absorbent surface being ideal for receiving the painted brushwork. The confectionery colours used at this period were usually of vegetable origin:

26

Red | saunders (red sandalwood), the East Indian tree |

Yellow | saffron, the dried stigmas of |

Green | the juice of spinach, |

Blue | ‘bluebottles’, the petals of the common cornflower, |

Violet | violet petals, |

The hardwoods, saunders and brazil, were reduced to fine chippings or to powder and boiled in a little water together with gum arabic, while the flower petals were ground in rosewater and the coloured juice squeezed out through a piece of cloth. Turnsole rags had only to be scalded in water to induce them to give up their colour.

All these colours were relatively safe to consume, especially since they were used in such small quantities, but other materials were positively poisonous, as may be seen from these examples mentioned by John Partridge in his book The Widowes Treasure, published in 1585:

27

‘ | the juice of rue, verdigris (basic copper acetate) and saffron |

Emerald green | verdigris, litharge (lead monoxide) and mercury, beaten together and ground ‘with the pisse of a young childe’ |

Gold | orpiment (arsenic trisulphate), ground with clear quartz, saffron powder and the gall of a hare or a pike, stored in a phial in a dunghill for five days, and kept for use |

It is amazing to find such recipes in any cookery book, since anyone who consumed even the smallest amount of some of these substances would certainly become dangerously ill, if not die.

Either gum-water (a solution of gum tragacanth) or egg white was used to provide a thickening and drying medium, which made the colours easy to apply with a brush and gave a hard finish, usually with a slight gloss. (Today you should use only the safe vegetable colours, needless to say, and the whites of sterilised eggs.) For denser colours and richer flavourings, the sugar plate could be mixed with finely ground and sifted spices, or the petals of marigolds, cowslips, primroses or roses first ground into some icing sugar with a little rosewater before being made up into a paste with more sugar and a little gum tragacanth.

28

In his recipe of 1562, Alexis of Piedmont had described sugar plate ‘whereof a man may make all manner of fruits and other fine things with their form, as platters, glasses, cups and suchlike things, wherewith you may furnish a table, and when you have done, eat them up, A pleasant thing for them that sit at table’.

29

A table completely set with sugar-plate tableware must have been very impressive, its pure white closely resembling expensive oriental porcelain or the milk-white variety of Venetian glass. It is most probable that for producing cups and other vessels in this way the confectioners made special moulds, but flat sweetmeat trenchers, about five inches (13cm) in diameter, could be easily rolled out and cut to size, leaving a blank area that would be ideal for elaborate painting and gilding. Small platters were easily executed too, simply by dusting a sheet of rolled-out sugar plate with icing sugar, patting it dusted-side-down on top of a metal or pottery plate, then trimming the edges and leaving it to dry.